Apprentice Minimum Wage to Rise to £8 from April 2026: What It Means for Young People and Employers

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Initial publication following HM Treasury Autumn Budget 2025 apprentice wage announcement

Government Confirms £8 Apprentice Minimum Wage

HM Treasury’s Autumn Budget 2025 confirmed statutory wage increases across all minimum wage rates from 1 April 2026. Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced the apprentice minimum wage will rise from £7.55 to £8.00 per hour, a 6% nominal increase. The rise affects apprentices under 19 years old and those aged 19 or over in their first year of apprenticeship, regardless of the apprenticeship level or sector.

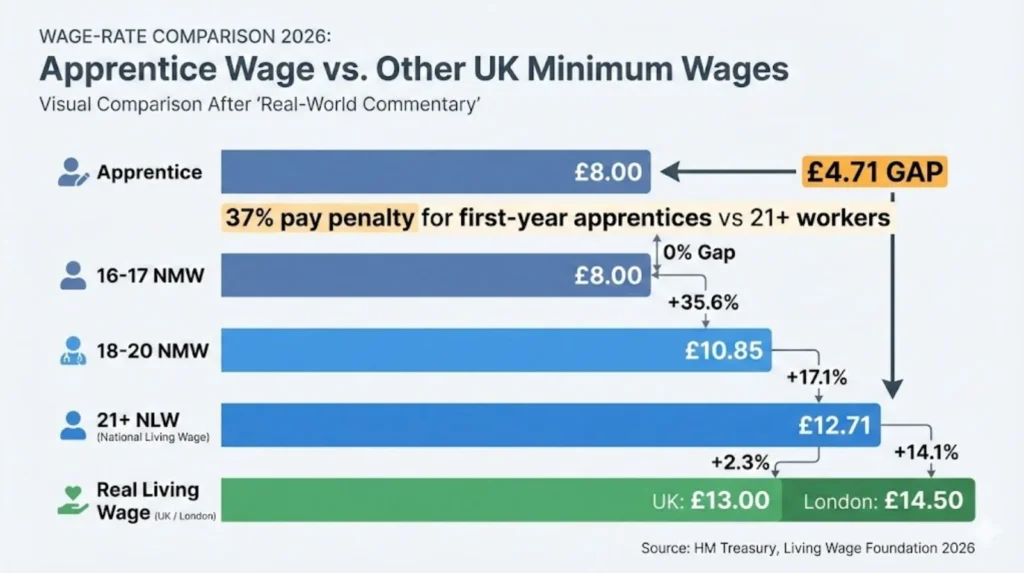

The National Living Wage (NLW) for workers aged 21 and over increases 4.1% from £12.21 to £12.71 per hour. The National Minimum Wage (NMW) for 18 to 20 year olds rises 8.5% to £10.85 per hour. The 16 to 17 year old rate increases to £8.00 per hour, aligning it exactly with the new apprentice rate. The accommodation offset, which allows employers to deduct costs for provided accommodation, rises to £11.10 per day.

Chancellor Reeves stated the increases ensure “people are properly rewarded for their hard work” while balancing worker needs with business affordability. The government estimates around 2.4 million low-paid workers will benefit from the combined wage increases across all statutory rates.

Eligibility Rules. The apprentice minimum wage applies specifically to apprentices under 19 and those aged 19 or over in their first year. Once an apprentice turns 19 and completes their first year, they legally become entitled to the age-appropriate National Minimum Wage rate. A 20-year-old in their second year of an apprenticeship must receive at least £10.85 per hour (the 18-20 NMW rate), not the apprentice rate. A 22-year-old in their second year must receive the full National Living Wage of £12.71 per hour.

The Low Pay Commission (LPC) recommendations were accepted in full by the government. The LPC advised balancing cost-of-living pressures, inflation forecasts (2% to 3% for 2026), business impact, and overall economic conditions when setting the rates. The Department for Education (DfE) and Department for Business and Trade (DBT) aligned with the LPC on maintaining the apprentice rate in line with the 16 to 17 year old rate rather than creating further separation.

Why the Rates Increased

The 6% apprentice wage increase sits against an economic backdrop of cooling but persistent inflation. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported annual Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation at 3.6% for October 2025, down from 3.8% in September 2025. CPIH (which includes housing costs) stood at 3.8%, down from 4.1%. This means the £8.00 apprentice rate represents a 2.4% real-terms increase in purchasing power (6% nominal minus 3.6% inflation).

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts real wage growth of around 5% in 2025, falling to 3.5% in 2026, then averaging 2.25% from 2027 onwards. Cumulative real wage growth is projected to be 0.75% higher than the March 2024 forecast for 2025-2026. Inflation is expected to peak in Q3 2025, then fall to the Bank of England’s 2% target by Q1 2027.

Real income trends for under-25s tell a different story. Resolution Foundation analysis shows this age group experienced largely stagnant real disposable income in 2026-2027, with growth only recovering to 0.5% by 2029. Youth unemployment is projected to peak at around 5% in the first half of 2026 before falling to 4.1% by 2030.

For apprentices specifically, the 6% rise is a genuine real-terms increase above the 3.6% inflation rate. But the starting point matters. The Living Wage Foundation calculates the Real Living Wage at approximately £13.00 per hour for the UK and £14.50 per hour for London in 2026. The £8.00 apprentice rate sits 38% below the UK Real Living Wage and 45% below the London rate.

A full-time apprentice working 37.5 hours per week at £8.00 earns £300 before tax, or approximately £15,600 annually. This falls below the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s minimum income standard for a single young adult without parental support. Rising costs for 16 to 24 year olds, particularly private rental inflation and transport costs, severely impact the financial viability of apprenticeships for those unable to live at home.

The government positioned the increase as addressing fairness, boosting productivity by valuing vocational training, and providing essential cost-of-living relief. The political commitment goes beyond pure economics. Labour’s manifesto pledged to phase out youth wage rates entirely and move towards a genuine living wage for all workers, making the £8.00 rate a transitional step rather than an endpoint.

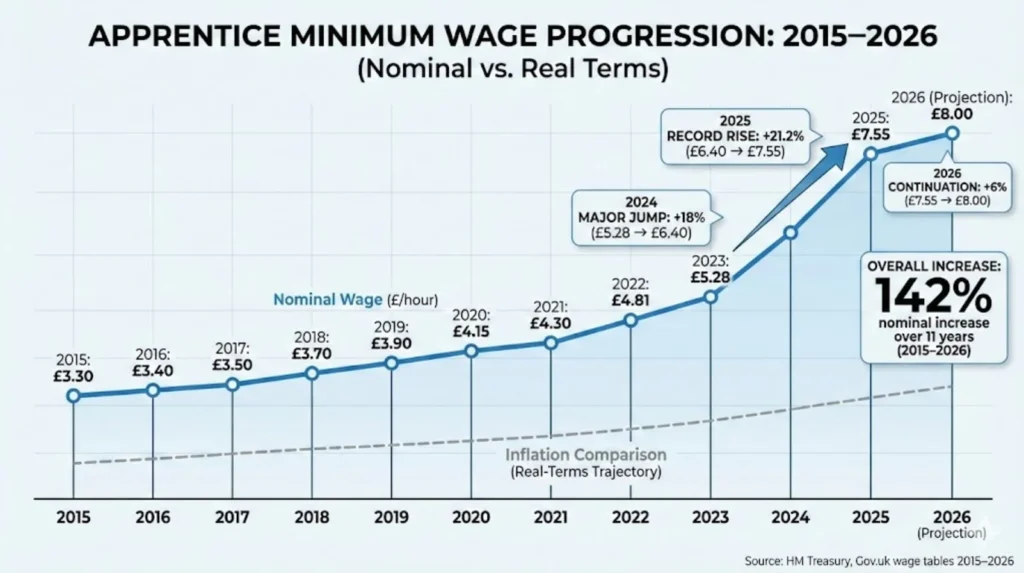

The apprentice minimum wage has climbed significantly since 2015, though the trajectory shows distinct phases of political intervention.

From 2015 to 2023, increases were modest and incremental. The rate rose from £3.30 (2015) to £3.40 (2016), £3.50 (2017), £3.70 (2018), £3.90 (2019), £4.15 (2020), £4.30 (2021), £4.81 (2022), and £5.28 (2023). These rises tracked slightly above inflation but maintained a substantial gap between the apprentice rate and other minimum wage thresholds.

The pattern changed dramatically in 2024. The government implemented an 18% increase, raising the rate from £5.28 to £6.40. This was the largest single percentage rise in the history of the apprentice minimum wage. The 2025 increase continued the momentum with a 21.2% rise to £7.55. The 2026 increase of 6% to £8.00 represents a slowdown compared to the previous two years, but still exceeds inflation by a significant margin.

Political positioning on apprentice pay varies widely. Labour’s stated aim is to abolish the sub-minimum-wage apprentice rate entirely and move towards paying all apprentices the full National Living Wage regardless of age or training year. The £8.00 rate is framed as progress towards this goal. The Conservatives, while in opposition, support the Low Pay Commission process but historically emphasised business affordability concerns and cautioned against increases that might reduce apprentice recruitment.

Trade unions, including the TUC and Unite, consistently call for abolishing the apprentice minimum wage as a separate category. Their position is that all apprentices should receive at least the National Living Wage (£12.71 from April 2026), arguing that lower pay penalises those choosing the vocational route and perpetuates class-based wage inequality. The £4.71 gap between the apprentice rate (£8.00) and the National Living Wage (£12.71) represents a 37% pay penalty for first-year apprentices compared to non-apprentice workers aged 21 and over.

Business groups, including the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) and the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), raised concerns about affordability during the 2024 and 2025 consultation rounds. The concern is that rapid cumulative increases reduce the financial incentive for small and medium enterprises to offer apprenticeships, particularly in low-margin sectors like hospitality, retail, and small-scale construction.

Sector Reactions

Training providers, employer groups, and think tanks responded to the announcement with mixed assessments balancing worker benefit against cost pressures.

The Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP) welcomed better pay for apprentices but raised concerns about funding band misalignment. AELP’s position is that increased wage costs without equivalent uplifts in government training funds place greater financial pressure on providers, especially those serving small and medium enterprises. The core issue is cashflow. Providers receive set funding per apprentice based on government funding bands, which have remained largely frozen. If employer wage costs rise significantly without corresponding funding increases, providers struggle to deliver high-quality training.

The Association of Colleges (AoC) called the rise a welcome step but insufficient to cover basic living costs. AoC highlighted that £8 per hour still fails to support an 18-year-old living independently in most of the South East. Their analysis points to the need for dedicated travel and commuter bursaries to address the transport cost barrier, which is frequently cited as a primary reason for apprentice drop-outs, particularly in rural areas and regions with poor public transport links.

The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) offered support, linking pay to long-term skills strategy and productivity. CIPD’s view is that cumulative wage rises are necessary to make apprenticeships a genuinely attractive alternative to Higher Education. Fair pay drives commitment and completion rates. Higher starting wages improve the perceived value of vocational training, countering the cultural bias towards university routes.

The Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) expressed caution. FSB representatives stated the increase is substantial when layered onto National Living Wage hikes for other staff. Small employers already facing high energy and materials costs may be forced to reduce the number of apprentices they take on. For a two-person electrical contracting business considering its first apprentice, the cumulative labour cost increase across 2024, 2025, and 2026 represents a significant budget commitment.

The Sutton Trust, a social mobility think tank, criticised the rate as remaining a barrier to participation for disadvantaged young people. While 6% is a real-terms increase, the low starting point means apprentices from low-income backgrounds are still significantly deterred by financial viability concerns. Young people from families unable to provide housing or financial support face impossible choices between low-paid apprenticeships and higher-paid entry-level jobs.

Youth Futures Foundation supported the rise, linking higher pay to NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) reduction. Their research shows higher pay is the most effective lever to attract disengaged young people into sustained, high-quality training pathways. But they emphasised pay alone is insufficient without better careers advice and structured support.

Wage Compression Concerns. A growing issue is the narrowing gap between apprentice pay and age-appropriate minimum wages. A 19-year-old in their second year earning £10.85 per hour (18-20 NMW) receives only 26% more than a first-year apprentice on £8.00. This compression reduces the perceived value of progression and creates tension around pay structures within firms employing apprentices at different stages.

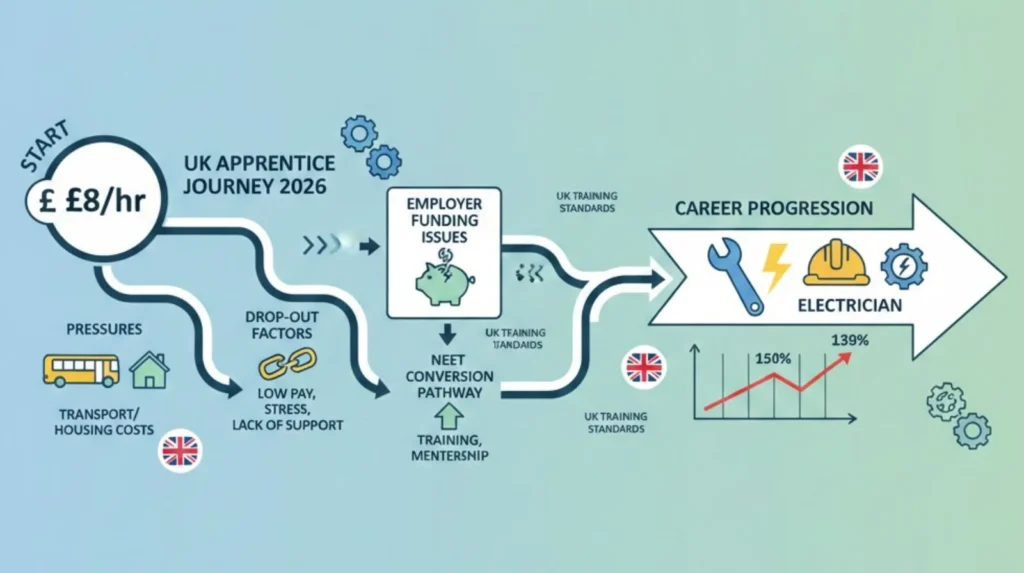

Participation, Drop-Out Rates and Retention

Department for Education (DfE) data reveals ongoing challenges with apprenticeship completion despite rising wages.

In 2023/24, there were 736,500 apprenticeship participants in England, with 339,600 new starts and 178,200 achievements (completions). Under-19s accounted for 32.7% of all starts, representing approximately 111,000 young apprentices beginning training. This cohort is most directly affected by the apprentice minimum wage since all under-19s receive the apprentice rate regardless of their training year.

The national achievement rate sits at approximately 60.5%, meaning around 40% of apprentices who start do not complete their qualification. Drop-out rates vary significantly by age. The 16 to 18 age group experiences the highest non-completion rates, reaching 40% in some sectors including hospitality, retail, and parts of construction. Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and Resolution Foundation strongly correlates low starting pay with higher drop-out rates, particularly among apprentices in non-levy-paying small and medium enterprises where pay typically sits at or very close to the statutory minimum.

The 47% drop-out figure linked to financial pressure comes from surveys asking withdrawn apprentices to identify their primary reason for leaving. Financial strain, inability to afford transport costs, and needing to take a higher-paid job to support themselves or contribute to family income dominated responses. Many apprentices reported needing second jobs to make ends meet, which directly impacted their ability to focus on training and complete portfolio requirements for qualifications like the NVQ Level 3.

Regional variation is stark. London has the lowest apprenticeship completion rates despite having the highest concentration of large employers and levy-funded programmes. The disconnect is explained by London’s cost of living. An apprentice on £8 per hour in London faces average rent of £800 to £1,200 per month for a room in a shared house, plus £150 to £200 monthly travel costs on Transport for London. The maths simply doesn’t work without parental support.

The North East shows the highest completion rates, correlating with lower living costs and stronger retention of young people in parental homes during training. Regional inequality in apprenticeship outcomes is as much about housing costs and transport infrastructure as it is about training quality or employer behaviour.

Joshua Jarvis, our Placement Manager, explains the financial reality:

"£8 per hour at 37.5 hours a week is £300 before tax, or about £15,600 annually. For an 18-year-old living independently in Birmingham or London, that doesn't cover rent, transport, and food. The reality is most apprentices still need parental support or a second job, which directly impacts their ability to focus on training and complete their NVQ."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

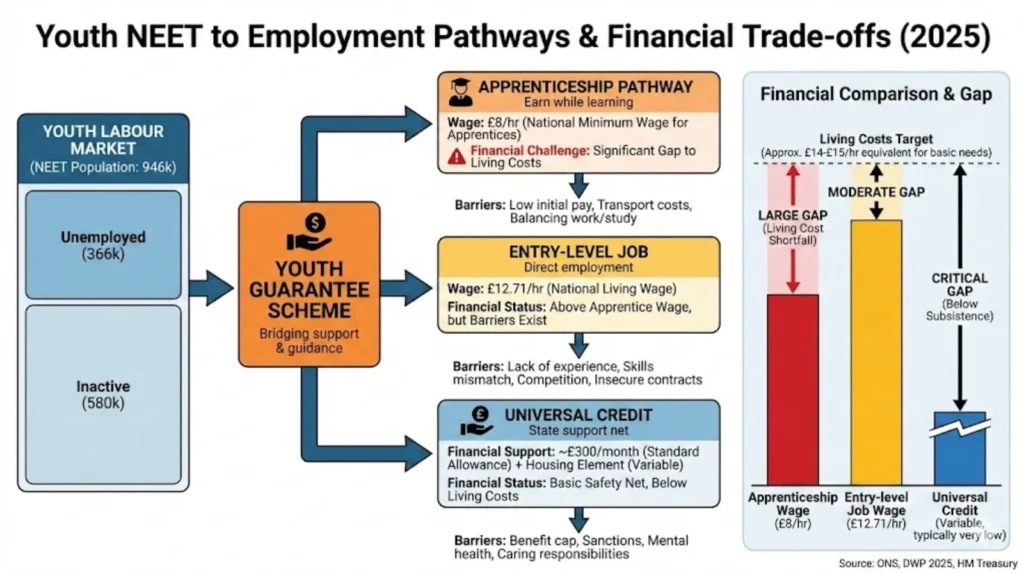

Youth Labour Market and NEET Context

The apprentice wage rise sits within a broader youth employment crisis. Approximately 946,000 young people aged 16 to 24 were classified as NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) in 2025, representing 12.7% of the age group. Of these, 366,000 were unemployed (actively seeking work), and 580,000 were economically inactive (not seeking work, often due to long-term illness, caring responsibilities, or discouragement).

DWP and ONS analysis identifies mental health and financial strain as primary drivers of youth inactivity. Long-term sickness, particularly mental health conditions, accounts for a significant portion of the inactive NEET cohort. For those who are unemployed rather than inactive, the financial calculation between benefits and low-paid apprenticeships becomes critical.

Universal Credit for 18 to 21 year olds provides approximately £300 per month standard allowance (before housing support). A full-time apprentice earning £15,600 annually (£8 per hour at 37.5 hours per week) significantly exceeds this, making apprenticeships financially preferable to unemployment benefits on paper. However, Universal Credit includes housing support, which can push total monthly income higher than apprentice wages in high-cost areas.

The Youth Guarantee scheme, announced alongside the wage increases, aims to ensure every 18 to 21 year old is guaranteed access to education, training, employment, or an apprenticeship. Pilots are running in trailblazer areas. Higher apprentice pay is used as a policy lever to make apprenticeships attractive options within the Youth Guarantee framework. But the £8 per hour rate is still £4.71 below the National Living Wage, creating a fundamental tension. Young people are being offered a “guarantee” of opportunities that may not be financially viable without family support.

DWP sanctions for refusing suitable employment or training create additional pressure. If a young person on Universal Credit is offered an apprenticeship under the Youth Guarantee and refuses it, they risk benefit sanctions. Forcing young people into apprenticeships paying £8 per hour when they cannot afford to live on that wage raises significant ethical questions about the policy’s sustainability.

Employer Impact and Funding Pressure

The financial impact on employers varies dramatically by size, sector, and existing pay structures.

Cost modelling for a first-year apprentice working 37.5 hours per week shows the increase from £7.55 to £8.00 adds £877.50 per year in gross labour costs (£0.45 per hour × 37.5 hours × 52 weeks). This excludes employer National Insurance contributions (approximately 13.8% on earnings above the secondary threshold) and mandatory pension contributions (minimum 3% employer contribution). The true additional cost per apprentice is closer to £1,050 annually when all statutory costs are included.

For small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that do not pay the Apprenticeship Levy, this represents a direct bottom-line cost. The FSB reports some members are reconsidering apprentice recruitment plans due to cumulative wage pressure across 2024 (18% rise), 2025 (21.2% rise), and 2026 (6% rise). A small electrical contracting firm employing two qualified electricians and considering taking on its first apprentice now faces an annual labour cost of approximately £16,650 (including NICs and pension), compared to £11,200 in 2023. That £5,450 increase over three years is substantial for businesses operating on margins of 8% to 12%.

Large levy-paying employers (those with annual payrolls exceeding £3 million) are generally less affected. Many already pay apprentices significantly above the statutory minimum to remain competitive. Engineering firms, large construction contractors, and financial services companies typically offer first-year apprentices £10 to £14 per hour. For these employers, the statutory rise to £8.00 has minimal direct impact, though it may create upward pressure on their existing pay structures to maintain differentials.

Apprenticeship Levy utilisation rates sit at around 50% to 60% in 2025, meaning large employers collectively leave approximately 40% of levy funds unspent and returned to the Treasury. The disconnect between levy underspend and SME funding pressure highlights structural problems. Large employers generate levy funds but struggle to recruit enough apprentices to spend them. SMEs want to recruit apprentices but face direct wage costs without access to levy funds.

Training provider sustainability is under strain. Providers operate on fixed government funding bands per apprentice, which have remained largely frozen since 2020. When apprentice wages rise without corresponding increases in funding bands, providers face a squeeze. They receive the same income per apprentice but must support employers dealing with higher wage costs, creating tension in the training ecosystem. AELP has repeatedly called for funding band reviews to align with wage increases.

International Comparisons

Switzerland operates highly variable cantonal and sector-specific apprentice wages, typically ranging from CHF 800 to CHF 1,200 per mon The UK’s £8.00 apprentice minimum wage sits low in international comparisons, particularly when adjusted for cost of living and social support structures.

Germany’s Ausbildung (dual vocational training system) sets statutory minimum monthly pay at approximately €900 to €1,200 (£750 to £1,000) for first-year apprentices, depending on sector and region. A UK apprentice on £8.00 per hour working 37.5 hours per week earns approximately £1,300 per month gross, appearing nominally higher. But the German system includes stronger social support, lower required work hours for equivalent qualifications, and structured cost-of-living adjustments within collective agreements. Real-terms comparison favours Germany once housing costs and living expenses are factored in.

th (£700 to £1,050). Swiss apprentices often live at home due to extremely high Swiss cost of living, making direct comparison difficult. But Swiss apprentices generally enjoy higher purchasing power relative to local living costs than UK apprentices.

The Netherlands’ BBL (vocational track) system pays apprentices approximately €500 to €1,000 per month (£420 to £840), varying by age and sector. Dutch rates are comparable to or slightly lower than UK rates nominally, but structured sector discounts for education, transport, and housing make the effective cost of living lower for Dutch apprentices.

Australia’s trades apprentice system operates on Award rates (sector-specific minimum wages). Stage 1 apprentices typically earn AUD 15 to AUD 25 per hour (£8 to £13), putting them at or above the UK rate. Australian apprentices benefit from higher nominal wages and a stage-based progression system that guarantees wage increases as competencies are demonstrated.

New Zealand sets apprentice minimum wages at approximately NZD 20 per hour (£9.50), with many apprentices paid above this rate by employers seeking to attract talent in tight labour markets. New Zealand’s approach treats apprentices closer to full employees with training attachments rather than as a separate, lower-paid category.

The UK stands as one of the lowest statutory starting points for apprentice pay compared to major international competitors with structured vocational training systems. The £8.00 rate represents approximately 63% of the UK National Living Wage (£12.71), whereas many dual systems in Europe maintain apprentice pay closer to 70% to 80% of adult minimum wages.

Cross-Industry Comparisons

Within the UK, the £8.00 apprentice minimum wage competes differently across sectors.

Retail apprenticeships typically pay £8 to £10 per hour. Large supermarket chains often pay slightly above the statutory minimum to attract applicants, but smaller independent retailers sit at or very close to £8.00. The retail sector relies heavily on young workers, making apprenticeships a recruitment channel, but the wage is not competitive against standard retail assistant roles paying £10 to £12.50 per hour.

Hospitality apprenticeships cluster around £8 to £9 per hour. The sector has historically used apprenticeships to access lower-cost labour, a practice increasingly criticised as exploitative. With 18 to 20 year old workers now entitled to £10.85 per hour on standard employment contracts, hospitality employers face wage compression that reduces the financial incentive to recruit apprentices versus standard staff.

Logistics and HGV apprenticeships pay approximately £9 to £12 per hour, above the statutory minimum. The sector faces chronic driver shortages, pushing wages upward. Apprentice HGV drivers often receive structured pay rises tied to licence progression (Category C, Category C+E), making the pathway financially viable.

Construction apprenticeships, particularly in electrical, plumbing, and carpentry trades, vary widely. JIB (Joint Industry Board) rates for electrical apprentices in 2026 range from approximately £8 to £12 per hour depending on stage and employer. Large commercial contractors typically pay towards the upper end. Small domestic installers often pay at or near the statutory minimum. At Elec Training, we work with employers across this range, and we see first-hand how pay levels affect apprentice retention and completion.

Engineering apprenticeships pay approximately £10 to £14 per hour, particularly in advanced manufacturing, aerospace, and automotive sectors. These employers compete for high-quality applicants and use pay as a differentiator. The statutory £8.00 minimum is largely irrelevant to their recruitment strategies.

FE (Further Education) traineeships offer weekly allowances of approximately £20 to £50 per week, far below the apprentice minimum wage. These are pre-apprenticeship programmes designed to build basic employability skills but offer minimal financial support, relying on parental or benefit income to sustain participants.

Universal Credit for 18 to 21 year olds provides around £335 per month standard allowance (before housing costs). A full-time apprentice earning £15,600 annually significantly exceeds this base rate, but once housing support is added to Universal Credit, the comparison becomes more complex. In high-cost regions, remaining on benefits with housing support can provide similar or better financial security than a low-paid apprenticeship.

The £8.00 rate is only genuinely competitive in sectors where employers typically pay minimum wage rates across their entire workforce. In high-value sectors with skilled labour shortages, it’s irrelevant because market rates far exceed statutory minimums.

Real-World Commentary

Forum discussions and social media reveal significant frustration with the gap between statutory rates and living costs.

Reddit’s r/Apprentices community includes recurring posts stating

"£8 per hour is still not enough to live on."

The sentiment is that the rate functions as an allowance rather than a wage, making independent living impossible. One representative comment noted:

"It's better, sure, but I can get a job at my local supermarket for £12.50. Why would I do an apprenticeship for £8 unless my parents cover my rent?"

The r/UKPersonalFinance subreddit highlights the differential impact:

"Big companies pay above minimum anyway, this only affects small firms."

The perception is accurate. Large employers with structured graduate and apprentice schemes already offer £10 to £15 per hour. The statutory rise to £8.00 primarily impacts smaller businesses and low-pay sectors where employers previously paid closer to the absolute minimum.

The r/UKJobs community emphasises non-wage barriers:

"Won't fix drop-out rates without travel cost reforms."

Strong consensus exists that high commuting and transport costs represent the primary financial barrier to retention. A £0.45 per hour rise (approximately £17.50 per week gross) does not address £100 to £150 monthly transport expenditure in many regions.

ElectriciansForums contributors report sector-specific frustration. One post stated:

"£8 per hour for a second-year construction apprentice is insulting. The company charges the client £200 a day for my work."

This highlights the disconnect between the value apprentices generate for employers (charged out at commercial rates) and the wages they receive (statutory minimums). The complaint is common in construction trades where apprentices perform productive billable work under supervision.

Twitter discussions frame the issue politically:

"It's a good step, but they need to stop calling it a big pay rise when it's still miles below the NLW. It's just less unfair now."

The sentiment reflects scepticism about government messaging that frames the increase as a major achievement when the £4.71 gap to the National Living Wage remains vast.

Policy Intersections

Other Budget 2025 measures interact with the apprentice wage rise, shaping its real-world impact.

The income tax personal allowance freeze extends until 2028. The threshold remains at £12,570, meaning a full-time apprentice earning £15,600 annually pays income tax on £3,030 of earnings (approximately £606 annually or £11.65 per week). This fiscal drag reduces the real value of future nominal wage increases. Any pay rise above £12,570 is immediately subject to 20% income tax, reducing take-home gains.

Proposed salary sacrifice pension caps could affect higher-paid apprentices in large employers, though the £8.00 statutory rate sits too low for this to be a direct concern. The principle matters. If non-wage benefits become less attractive or restricted, workers demand higher nominal pay to compensate. This creates upward pressure on wage structures, including apprentice pay.

The rail fare freeze offers potential real-terms savings for apprentices relying on public transport. If annual rail fare increases are frozen while wages rise, apprentices gain modest purchasing power improvements that partially offset high commuting costs. However, regional variation matters. Apprentices in rural areas with minimal public transport see no benefit.

NHS prescription charge freezes provide minor cost-of-living relief for apprentices with ongoing medical conditions. The impact is small but symbolically aligned with reducing cost pressures on low-income young people.

Student loan repayment threshold changes make the apprenticeship route more financially attractive compared to Higher Education. As university graduates face lower repayment thresholds and higher lifetime repayment totals, the apprenticeship pathway (with no tuition debt and immediate earnings) becomes comparatively more appealing. The apprentice wage rise strengthens this comparison, though the low absolute starting pay remains a barrier.

DWP sanctions tightening under the Youth Guarantee creates additional complexity. If 18 to 21 year olds on Universal Credit are required to accept apprenticeship offers or face benefit sanctions, the £8 per hour wage must be sufficient to live on without family support. Forcing young people into financially unviable apprenticeships risks creating a cycle of poverty, drop-outs, and re-entry to benefits.

Energy bill reductions announced in Budget 2025 (£150 average cut) indirectly support apprentices by reducing household costs. For apprentices living at home, this benefits their families. For independent apprentices, lower energy costs marginally improve affordability, though the effect is small relative to rent and transport pressures.

Wage Trends in Context

Placing the 2026 rise within longer-term wage trends reveals both progress and persistent problems.

From 2016 to 2026, the apprentice minimum wage increased 135% nominally, from £3.40 to £8.00. Adjusted for cumulative inflation over the same period (approximately 30%), the real-terms increase is approximately 81%. This represents genuine purchasing power growth, making apprenticeships more financially viable than a decade ago.

But comparison to other minimum wage categories shows relative decline. The National Living Wage (21+) increased from approximately £7.20 (2016) to £12.71 (2026), a 76% nominal rise. The apprentice rate grew faster in percentage terms but started from a much lower base, meaning the absolute gap widened. In 2016, an apprentice earned approximately 47% of the National Living Wage. In 2026, an apprentice earns approximately 63% of the National Living Wage. Progress, but substantial inequality remains.

Inflation-adjusted apprentice wages show the 2026 rate at approximately £7.74 in real 2025 prices (nominal £8.00 minus 3.6% projected inflation). This sits significantly higher than pre-2024 levels but lower than if adjusted using a bespoke youth cost-of-living index that weights rental inflation heavily. Young people’s cost-of-living has risen faster than general CPI due to housing costs.

Recruitment numbers versus wage changes show no simple correlation. Apprenticeship starts spiked in 2016/17 (pre-Levy introduction at around 509,000) despite low wages. Starts fell significantly between 2017 and 2020 (dropping to around 322,000) despite modest wage increases. Starts recovered slightly in 2023/24 (approximately 337,000) coinciding with the largest wage rises. This suggests recent wage increases may have positively impacted demand from applicants without yet significantly curtailing supply from employers.

Placing the 2026 rise within longer-term wage trends reveals both progress and persistent problems.

From 2016 to 2026, the apprentice minimum wage increased 135% nominally, from £3.40 to £8.00. Adjusted for cumulative inflation over the same period (approximately 30%), the real-terms increase is approximately 81%. This represents genuine purchasing power growth, making apprenticeships more financially viable than a decade ago.

But comparison to other minimum wage categories shows relative decline. The National Living Wage (21+) increased from approximately £7.20 (2016) to £12.71 (2026), a 76% nominal rise. The apprentice rate grew faster in percentage terms but started from a much lower base, meaning the absolute gap widened. In 2016, an apprentice earned approximately 47% of the National Living Wage. In 2026, an apprentice earns approximately 63% of the National Living Wage. Progress, but substantial inequality remains.

Inflation-adjusted apprentice wages show the 2026 rate at approximately £7.74 in real 2025 prices (nominal £8.00 minus 3.6% projected inflation). This sits significantly higher than pre-2024 levels but lower than if adjusted using a bespoke youth cost-of-living index that weights rental inflation heavily. Young people’s cost-of-living has risen faster than general CPI due to housing costs.

Recruitment numbers versus wage changes show no simple correlation. Apprenticeship starts spiked in 2016/17 (pre-Levy introduction at around 509,000) despite low wages. Starts fell significantly between 2017 and 2020 (dropping to around 322,000) despite modest wage increases. Starts recovered slightly in 2023/24 (approximately 337,000) coinciding with the largest wage rises. This suggests recent wage increases may have positively impacted demand from applicants without yet significantly curtailing supply from employers.

Contradictions and Disputes

Stakeholders hold fundamentally opposing views on the apprentice wage rise, reflecting deeper disagreements about labour market policy.

Employers, particularly the FSB, argue:

"We can't afford higher wages. This reduces recruitment."

The position is grounded in genuine cost pressures. Small businesses facing high energy costs, material inflation, and cumulative wage increases across their entire workforce see apprentice wage rises as additional burden that may force them to hire fewer apprentices or abandon recruitment entirely.

Unions, including the TUC and Unite, counter:

"£8 is nowhere near enough. It should match the National Living Wage."

Their position is that lower apprentice pay perpetuates class-based wage inequality and penalises young people choosing vocational routes. Fair pay should be universal, not age-dependent. The £4.71 gap between £8.00 and £12.71 is unjustifiable.

Economists, particularly from the Resolution Foundation, note:

"Real-terms apprentice pay is still down compared to 2018."

When adjusted for bespoke cost-of-living indices that weight youth-specific costs (particularly housing), the purchasing power of the apprentice wage remains below previous peaks despite recent nominal increases. The 2024-2026 rises represent recovery, not breakthrough.

Politicians, particularly Labour representatives, claim:

"Boosting apprentice pay will drive productivity."

The argument is that higher pay increases applicant quality, improves retention, and creates stronger commitment to training completion. Better-paid apprentices become more productive, better-skilled workers, justifying the investment.

Training providers, represented by AELP, warn:

"Wage rises without funding rises hurt SMEs."

Without increases in Apprenticeship Funding Bands to match rising wage costs, providers cannot adequately support employers absorbing higher labour costs. This leads to either reduced training quality or fewer SME placements, undermining the system.

Young people, across social media platforms, state simply:

"£8 per hour is still below basic living costs."

Anecdotal evidence confirms apprentices require parental support or second jobs to manage rent and transport, limiting the effectiveness of apprenticeships as full-time, self-sustaining opportunities. The wage rise helps, but the gap to financial independence remains vast.

Thomas Jevons, our Head of Training, offers a measured perspective:

"Higher pay helps retention, but it's not the only factor. Apprentices drop out because of poor-quality placements, lack of structured training, or realising the work isn't for them. Raising the wage to £8 won't fix apprenticeships where learners spend three years making tea and pulling cables without proper NVQ portfolio development."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

What To Do Next

The £8.00 apprentice minimum wage from April 2026 represents genuine progress in narrowing the gap between apprentice pay and broader minimum wage rates. The 6% nominal increase delivers a 2.4% real-terms improvement at a time when youth unemployment and NEET figures remain concerningly high. For young people considering apprenticeships, the rate makes the pathway marginally more viable than it was at £7.55.

But the structural problems persist. The £4.71 gap to the National Living Wage means apprentices face a 37% pay penalty compared to non-apprentice workers aged 21 and over. The £8.00 hourly rate translates to £15,600 annually for full-time work, falling well short of independent living costs in most UK regions. Drop-out rates remain stubbornly high, particularly among under-19s, with financial pressure cited as the primary reason for withdrawal in 47% of cases.

The policy creates winners and losers. Large levy-paying employers already paying above the statutory minimum see minimal impact. Small and medium enterprises face genuine cost pressures that may reduce apprentice recruitment. Training providers struggle with frozen funding bands that don’t match rising wage costs. Young people from families unable to provide housing or financial support remain locked out of apprenticeships that should theoretically offer pathways to skilled employment.

International comparisons show the UK’s apprentice pay remains among the lowest in comparable vocational training systems. Germany, Switzerland, Australia, and New Zealand all maintain higher effective wages or stronger non-wage support structures for apprentices. The UK’s 63% ratio of apprentice pay to National Living Wage sits below the 70% to 80% typical in dual systems.

Cross-industry analysis reveals the £8.00 rate is only competitive in low-pay sectors like retail and hospitality. In construction, engineering, and other skilled trades where market rates far exceed statutory minimums, the policy has minimal direct impact. The statutory minimum sets a floor, but the ceiling is determined by sector-specific labour shortages and employer recruitment strategies.

For those exploring electrical apprenticeships and vocational training pathways, understanding the full financial picture matters. The apprentice wage is one component of a complex calculation including housing costs, transport expenses, training quality, and long-term qualification outcomes. At Elec Training, we work with apprentices navigating these realities daily, helping them understand the full pathway from entry-level pay through to qualified electrician earnings that can reach £35,000 to £45,000 with the right qualifications and experience. If you’re considering an electrical apprenticeship or adult training route, understanding how wages progress beyond the first-year minimum is essential. You can explore training options and speak to our team at www.elec.training or call 0330 822 5337 for guidance on pathways that lead to sustainable electrical careers.

References

- HM Treasury – Autumn Budget 2025 (26 November 2025) – https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/budget-2025

- Gov.uk – National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage Rates (2026) – https://www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage-rates

- Low Pay Commission – 2026 Minimum Wage Recommendations Report – https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/low-pay-commission

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) – Consumer Price Inflation (October 2025) – https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

- Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) – Economic and Fiscal Outlook (November 2025) – https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

- Department for Education (DfE) – Apprenticeship Statistics (2023/24) – https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/apprenticeships-and-traineeships

- Resolution Foundation – Youth Labour Market Analysis 2025 – https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/

- Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) – Apprenticeship Drop-out Rates and Financial Barriers – https://ifs.org.uk/

- Association of Employment and Learning Providers (AELP) – Response to Budget 2025 – https://www.aelp.org.uk/

- Association of Colleges (AoC) – Apprentice Pay and Retention Analysis – https://www.aoc.co.uk/

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) – Labour Market Outlook 2025 – https://www.cipd.co.uk/

- Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) – Impact of Wage Increases on SME Recruitment – https://www.fsb.org.uk/

- Sutton Trust – Social Mobility and Apprenticeship Access – https://www.suttontrust.com/

- Youth Futures Foundation – NEET Reduction Strategies – https://youthfuturesfoundation.org/

- Living Wage Foundation – Real Living Wage 2026 Rates – https://www.livingwage.org.uk/

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation – Minimum Income Standards for Young Adults – https://www.jrf.org.uk/

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 11 December 2025. This article reflects HM Treasury Autumn Budget 2025 announcements published 26 November 2025. Apprentice minimum wage increases to £8.00 per hour from 1 April 2026 (confirmed). National Living Wage rises to £12.71 (+4.1%), NMW 18-20 rises to £10.85 (+8.5%), both effective 1 April 2026. Inflation figures use ONS CPI data (October 2025: 3.6%). OBR wage growth forecasts and youth unemployment projections from Economic and Fiscal Outlook November 2025. DfE apprenticeship participation data from 2023/24 academic year (latest available). Drop-out rates and financial pressure correlations from IFS and Resolution Foundation research (2024-2025). International wage comparisons use 2025-2026 exchange rates and statutory minimums (Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand). NEET figures from ONS Labour Force Survey (2025). Sector reactions compiled from AELP, AoC, CIPD, FSB statements (November 2025). Youth Guarantee scheme details from DWP policy announcements (2025). Real-terms calculations use 2025 baseline prices. Next review scheduled following April 2026 implementation and publication of first-quarter 2026 ONS wage data.