Electrical Apprenticeships in the UK: What They Actually Involve (And Who They Actually Suit)

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Updated with 2026 apprenticeship start data and current JIB wage rates

Electrical apprenticeships get marketed as the “proper” route into the trade, and in many ways, they are. But the gap between the marketing and the reality is substantial enough that roughly half of people who start one don’t finish.

That’s not a criticism of apprenticeships themselves. It’s an acknowledgment that they’re designed for a specific type of person in a specific life situation, and if you don’t fit that profile, four years of low wages and uncertain progression can become unsustainable fast.

This guide breaks down what electrical apprenticeships actually involve in the UK, who they genuinely suit, what the competition looks like, why so many people drop out, and what alternatives exist if the traditional apprenticeship route doesn’t align with your circumstances.

What Electrical Apprenticeships Actually Are

Let’s clear up the single biggest misconception immediately: an electrical apprenticeship is not a college course with some work experience attached. It’s a full-time job with mandatory training built into it.

You are an employee first. Your employer pays your wage, assigns your daily tasks, provides supervision, and ensures you’re gathering the on-site experience you need for your portfolio. The training provider (typically a college or private training center) delivers the theoretical component, but they’re not your boss and they don’t find you work.

The standard for electrical apprenticeships in England is the Installation Electrician / Maintenance Electrician Level 3. This defines what you must know, do, and demonstrate by the end of your apprenticeship. It covers installation work, testing and inspection, fault diagnosis, and understanding BS 7671:2018+A2:2022 (the UK wiring regulations).

Duration is typically 42-48 months. That’s three and a half to four years. Some apprenticeships with prior experience or accelerated pathways might shorten this slightly, but the vast majority follow the full timeline because that’s how long it genuinely takes to build competence across domestic, commercial, and industrial contexts.

The structure splits into two parts:

Off-the-job training (20% of your working hours): This is college time, typically one day per week or block release. You’ll study electrical principles, circuit design, safety regulations, and practice tasks in workshops. This covers the theory side, teaching you why things work the way they do and what BS 7671 requires.

On-the-job learning (80% of your working hours): This is site work under the supervision of qualified electricians. You’ll install cables, wire consumer units, test circuits, diagnose faults, and build the practical skills that turn theory into applied competence. Your employer documents this experience in your portfolio, which proves you’ve performed the tasks the assessment requires.

At the end, you sit the End-Point Assessment (EPA), which includes the AM2S practical exam. This is an independent evaluation testing whether you can work safely and competently to industry standards. Passing the EPA plus completing your portfolio earns you NVQ Level 3 status and eligibility for the JIB/ECS Gold Card, which is the industry-recognized proof you’re a qualified electrician.

The apprenticeship is free to you. Government funding covers the training costs via the apprenticeship levy (for larger employers) or co-funding (for smaller ones). You don’t pay tuition fees. However, you do earn significantly less during those four years than you would in most other entry-level work, which is where the financial pressure starts.

Who Apprenticeships Actually Suit

Apprenticeships work brilliantly for specific people in specific circumstances. They work poorly for others, and pretending otherwise sets people up for frustration.

Ideal candidates: School leavers aged 16-20 with family support

If you’re finishing school, living with parents who can subsidize your low wages, and you have four years to commit without major financial obligations, apprenticeships offer an unbeatable deal. You’ll gain recognized qualifications, site experience, and industry connections without accruing student debt. By your mid-20s, you’ll be a qualified electrician earning £30,000-£45,000 depending on location and specialization.

This demographic has time on their side. Four years feels long at 18, but at 22 you’re still young with your entire career ahead. The low starting wages (£10,000-£18,000 annually) are manageable when you’re not paying rent, mortgages, or supporting dependents.

Difficult for: Adults over 25 with financial responsibilities

Career changers face two major barriers. First, apprentice wages. If you have rent, car payments, a mortgage, or children, earning £12,000-£15,000 in year one isn’t viable without significant savings or a partner’s income. Most adults simply can’t sustain that level of pay reduction for four years.

Second, competition. Employers prioritize younger candidates because government funding fully covers under-19s, while over-22s require co-funding contributions. When choosing between an 18-year-old and a 28-year-old with identical enthusiasm, the financial incentive favors the younger applicant. This isn’t age discrimination in the legal sense, but it’s a structural barrier that makes placements harder for adults.

Suits: People who prefer hands-on learning

If classroom theory bores you but physical problem-solving excites you, apprenticeships match your learning style. The 80/20 split (mostly site work, some college) emphasizes practical application over academic study. You’ll still need to pass theory exams and understand electrical principles, but the bulk of your time involves doing rather than reading.

Struggles: Those needing quick qualification

Four years is a long commitment. If you need to be earning qualified-level wages within 12-18 months due to financial pressure or life circumstances, apprenticeships won’t deliver that. Alternative routes (like adult learner college courses combined with NVQ assessment) can achieve Gold Card status in 18 months to 2 years, though they require different trade-offs like upfront course fees and self-sourcing work experience.

Suits: People with transport flexibility

Electrical work involves traveling to different sites, often with early starts (7am or earlier). If you can drive and have a car, you’re significantly more employable. If you rely on public transport, you’ll be limited to employers whose sites align with bus or train routes, which reduces your placement options substantially.

Struggles: Those with rigid schedule requirements

Apprenticeships occasionally require overtime, weekend work, or adjusting to project demands. If you need fixed hours due to childcare or other commitments, some employers won’t be flexible. This isn’t universal (some firms are very accommodating), but it’s common enough to create friction for people with inflexible personal circumstances.

The bottom line: apprenticeships are designed around the traditional model of young people entering the workforce directly from school. They work well for that demographic. They work less well for everyone else, not because those people lack ability or commitment, but because the structure doesn’t accommodate different life stages.

The Reality of Getting an Apprenticeship

Securing an electrical apprenticeship is competitive. Very competitive. In some regions, applicants outnumber openings by 200:1 or more.

Entry requirements (academic minimum):

Most employers require:

- 4-5 GCSEs at grade 4/C or above

- Must include English, Maths, and ideally Science

- Some accept Level 2 Functional Skills as alternatives

Maths matters particularly because electrical theory involves algebra, trigonometry, and calculations for voltage drop, cable sizing, and circuit design. You don’t need A-level maths, but you do need competence beyond basic arithmetic.

Entry requirements (practical reality):

Academic qualifications get you past the first filter. What actually secures placements:

A driving license significantly improves your chances. Employers want apprentices who can travel to different sites independently without relying on public transport or lifts from qualified electricians.

Basic trade knowledge demonstrates genuine interest. If you can explain the difference between AC and DC current, or why RCDs exist, you stand out from applicants who’ve done zero research.

Work experience in any manual trade helps. Even non-electrical construction work (laboring, carpentry, general site assistance) shows you understand physical work, safety requirements, and construction environments.

Local connections matter. Small electrical firms often hire apprentices through word-of-mouth or recommendations from existing staff. Networking with local contractors (politely asking about apprenticeship opportunities, offering to shadow for a day, demonstrating enthusiasm without being pushy) opens doors that online applications alone don’t.

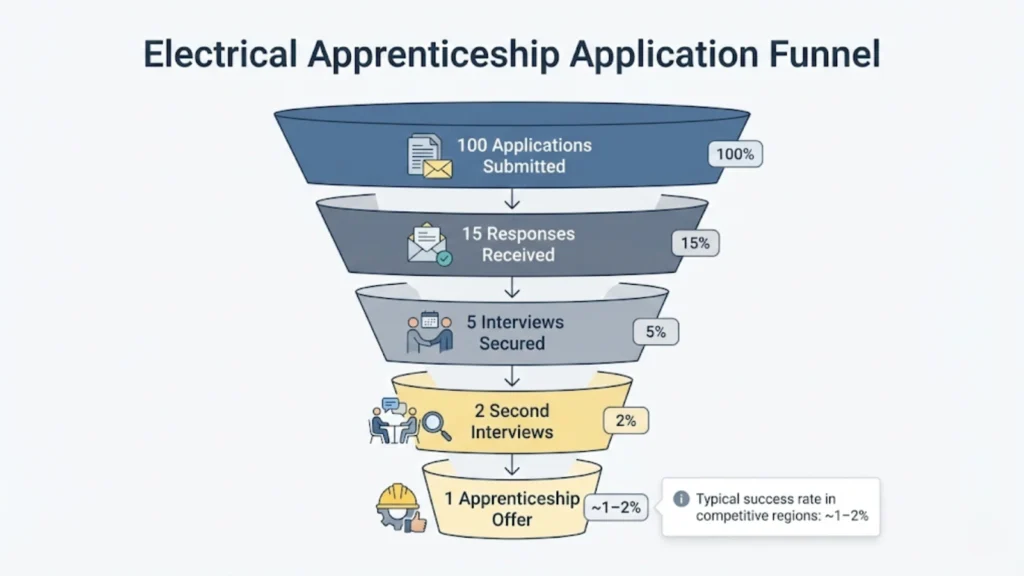

The competition numbers:

Electrical apprenticeships face approximately 227 applications per opening in competitive regions. This varies dramatically by location. London and the South East have more vacancies but fiercer competition. Rural areas have fewer opportunities but also fewer applicants.

Recent data shows apprenticeship starts in construction trades declining by 11-16% year-on-year. Fewer placements exist than five years ago, making competition even tighter. The government’s push to increase apprenticeship numbers hasn’t translated into substantially more electrical opportunities because the bottleneck is employer willingness to take on apprentices, not government funding.

How to actually find apprenticeships:

GOV.UK’s “Find an Apprenticeship” service lists official vacancies. Check it daily, apply promptly, and tailor applications to each employer rather than sending generic CVs.

Training providers like JTL, EIT, and others sometimes help match applicants with employers. Register with multiple providers to maximize opportunities.

Direct approaches to local electrical contractors work. Prepare a short pitch explaining why you want to become an electrician, what you understand about the role, and why you’d be reliable. Most firms won’t have advertised vacancies but might consider taking someone on if you demonstrate genuine commitment.

Expect rejections. Lots of them. If you apply to 50 firms and get 3 interviews, you’re doing well. If those 3 interviews lead to 1 apprenticeship offer, you’ve succeeded. The process is frustrating, time-consuming, and demoralizing when rejections pile up, but persistence is required.

Getting an apprenticeship requires treating it like a job hunt, not a college application. You’re competing with hundreds of others for limited spots. The ones who succeed combine academic qualifications with practical enthusiasm, flexibility, and relentless persistence.

What Apprentices Actually Earn

Apprentice wages are low. Legally low. Often shockingly low compared to other entry-level work.

The Apprentice Minimum Wage (as of April 2024) is £6.40 per hour. This applies to all apprentices under 19, or those 19+ in their first year. After completing year one, apprentices aged 19+ must receive at least the National Minimum Wage for their age bracket (currently £11.44/hour for ages 21+).

Most electrical employers pay slightly above these minimums to remain competitive and retain apprentices. Typical electrical apprentice wages follow JIB rates:

Year 1: £8.16–£10.50/hour (approximately £10,000–£14,000 annually)

Year 2: £10.00–£12.00/hour (approximately £13,000–£16,000 annually)

Year 3: £12.00–£14.00/hour (approximately £16,000–£19,000 annually)

Year 4: £14.00–£16.00/hour (approximately £19,000–£22,000 annually)

These are averages. Some firms pay more, especially large contractors in high-cost areas. Others stick to legal minimums. Regional variations exist, with London and South East firms typically paying higher wages to offset living costs.

Compare this to warehouse work (often £11–£13/hour with immediate start), hospitality roles, or retail management (often £22,000–£28,000 for assistant manager positions). In the short term, apprentices earn substantially less than many unskilled roles. This is why financial sustainability becomes the primary reason adults struggle with apprenticeships.

Hidden costs:

While training is funded, you’ll need to purchase hand tools over time. Basic essentials (screwdrivers, pliers, wire strippers, multimeter) cost £200–£400 initially. Work boots, high-visibility clothing, and safety equipment add another £100–£200.

Travel costs to sites can be substantial if you don’t have a car. Fuel, insurance, and vehicle maintenance become necessary expenses for mobile site work.

The long-term payoff:

Once qualified, electricians typically earn £30,000–£45,000 annually depending on location, sector, and experience. Self-employed electricians in high-demand areas can invoice £40–£50/hour, translating to £50,000–£70,000+ annually with good client bases.

Understanding recent JIB pay rises helps contextualize post-qualification earning potential and how wages progress through different electrician grades.

The four-year investment in low wages eventually pays back. But “eventually” means year five or six of your electrical career, which is cold comfort when you’re earning £12,000 in year one with bills to pay.

For school leavers living with parents, this trade-off makes sense. For 28-year-olds with mortgages, it often doesn’t. The mathematics of apprentice wages favor people without substantial financial obligations, which is why age and life stage correlate so strongly with apprenticeship suitability.

College Theory vs Site Reality

The apprenticeship split between college (20% time) and site work (80% time) sounds straightforward. In practice, there’s often a significant gap between what you learn in each environment.

College focuses on theory:

You’ll study electrical principles (Ohm’s Law, power calculations, circuit behavior), BS 7671 wiring regulations (cable sizing, protective devices, earthing systems), and safety procedures (isolation methods, testing sequences, risk assessments). College workshops provide controlled environments where you practice tasks like terminating cables, wiring consumer units, and using test equipment.

This theoretical foundation is essential. You need to understand why protective devices are sized the way they are, not just how to install them. You need to grasp earth fault loop impedance concepts, not just memorize test result limits.

But college conditions differ dramatically from real sites. Workshop circuits are pre-wired for learning. Materials are always available. You’re not working in a cramped loft space or a muddy construction site in December. Time pressure doesn’t exist because you’re practicing, not meeting project deadlines.

Sites focus on productivity:

When you start on-site work, employers need to balance your learning with their business operations. This means you’ll often spend substantial time on repetitive tasks that build familiarity but don’t necessarily expand your competence range.

First-year apprentices commonly spend months pulling cables, chasing walls for containment, or preparing materials for qualified electricians. These are necessary tasks and you do learn from them, but they’re basic compared to what your EPA will test.

The quality of your site experience depends entirely on your employer. A good employer rotates you through different job types (domestic, commercial, testing, fault-finding), explains the reasoning behind decisions, involves you in planning, and treats you as a developing professional.

A poor employer treats you as cheap labor for grunt work. You might spend two years doing domestic rewires exclusively, never touching commercial installations or three-phase systems. When your EPA tests industrial knowledge, you’ll struggle because your employer never provided that exposure.

"College teaches you Ohm's Law and earthing systems in controlled conditions. Sites teach you how to work fast under pressure. The apprenticeship works when both elements align, but if you're only doing one type of installation for years, you'll struggle with the breadth the End-Point Assessment demands."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

This misalignment between college theory and site practice creates challenges. Some apprentices find college frustrating because it feels disconnected from what they do daily. Others find site work frustrating because they’re not applying what they’ve learned in workshops.

The apprenticeship model assumes you’ll experience a broad range of electrical work over four years. When that assumption holds true (good employer providing varied exposure), the system works brilliantly. When it doesn’t (employer with limited job diversity or unwillingness to invest in apprentice development), completion becomes significantly harder.

Supervision matters as well. Initially, you work under constant oversight. Gradually, as competence develops, supervision reduces. But you’re never working fully independently until after qualification. This staged progression makes sense from a safety and learning perspective, but it can feel restrictive for people used to autonomy in previous careers.

The portfolio you build throughout your apprenticeship must demonstrate competence across the full breadth of the standard. If your employer hasn’t provided opportunities to gather that evidence, you’ll need to source additional experience elsewhere or extend your apprenticeship timeline.

For apprentices interested in specializing after qualification in areas like building management systems skills, the foundational apprenticeship provides the essential grounding in electrical principles and BS 7671 compliance that more advanced certifications build upon.

Why So Many People Don't Finish

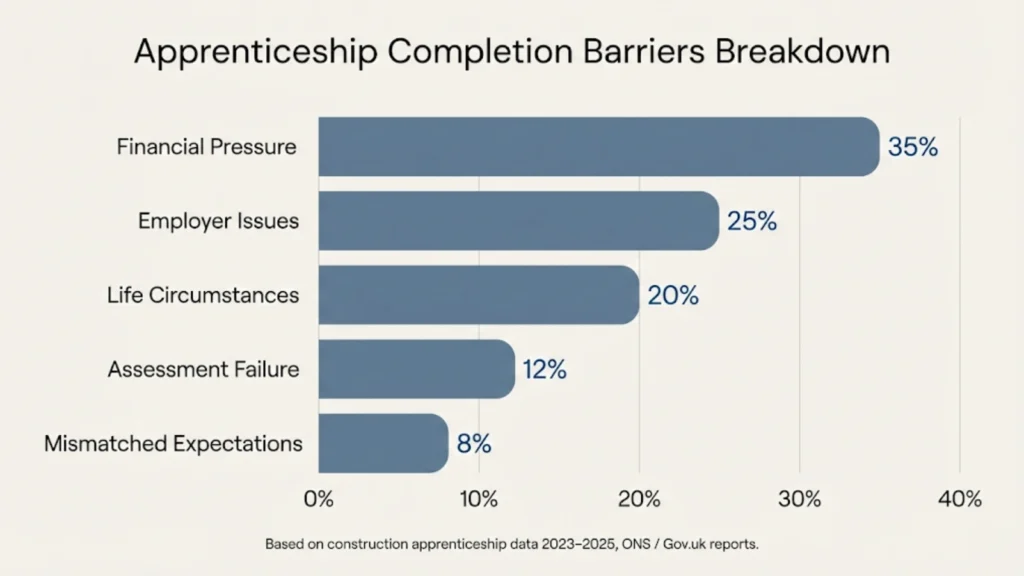

Completion rates for electrical apprenticeships hover around 40–60% depending on the data source. Roughly half of people who start an apprenticeship don’t finish it.

That’s not a commentary on individual failure. It’s a structural reality shaped by financial pressures, employer behavior, and life circumstances that change over four years.

Primary reason: Financial pressure

Adults quickly realize they can earn more in non-skilled work. A warehouse operative often earns £11–£13/hour immediately with no training period. An apprentice earns £8–£10/hour in year one and doesn’t reach equivalent wages until year three or four.

When rent is due, car insurance needs paying, or unexpected expenses arise, the apprentice wage becomes unsustainable. People leave not because they don’t want to be electricians, but because they can’t afford to continue.

Secondary reason: Poor employer support

Some employers hire apprentices for cheap labor without genuine commitment to training. They assign repetitive tasks indefinitely, don’t provide portfolio evidence variety, and don’t mentor effectively. Apprentices in these situations find themselves 18 months in without sufficient documented evidence to progress.

Others face employer business problems. Small firms losing contracts, going bust, or downsizing often let apprentices go first. When this happens mid-apprenticeship, the apprentice must find a new employer willing to take them on, which is difficult because most employers prefer starting from year one rather than inheriting someone else’s partially trained apprentice.

Third reason: Life circumstances

Four years is a long time. People have children, family members fall ill, relationships end, housing situations change. Apprenticeships require stable life circumstances because they’re rigid commitments. When life becomes unstable (as it often does in your late teens and early twenties), maintaining the apprenticeship becomes secondary to dealing with immediate crises.

Fourth reason: AM2S failure

The End-Point Assessment, particularly the AM2S practical exam, has a significant first-attempt fail rate. The assessment tests installation work, testing procedures, fault diagnosis, and inspection under time pressure. It’s a genuine competence test, not a box-ticking exercise.

Apprentices who fail AM2S can retake it, but each attempt costs £700–£1,000. Multiple failures become financially and emotionally draining. Some people walk away after one or two failed attempts, feeling the qualification isn’t achievable.

Fifth reason: Mismatched expectations

Some people enter apprenticeships thinking they’ll be “hands-on” immediately, doing exciting electrical work from day one. The reality of spending months on basic tasks (cable pulling, wall chasing, material prep) frustrates them. They leave thinking the trade isn’t what they expected, when actually they left before experiencing the work qualified electricians do.

"Finishing an apprenticeship doesn't guarantee immediate high earnings. Newly qualified electricians still need experience before they're trusted with complex work or earn top rates. The Gold Card proves competence, but employers look at your site history, references, and whether you can work independently. The four-year investment pays off eventually, but 'eventually' might mean year five or six."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

The 50% non-completion rate doesn’t mean apprenticeships are broken. It means they’re designed for specific circumstances, and when those circumstances don’t align (financial stability, good employer, stable personal life), completion becomes significantly harder.

For those who do finish, the investment pays off. But pretending everyone succeeds, or that non-completion reflects personal failure rather than structural barriers, sets unrealistic expectations that harm people considering this route.

Understanding the progression opportunities beyond basic qualification, including achieving approved status and the associated earnings increases, helps contextualize why the four-year apprenticeship investment eventually delivers returns despite the challenging early years.

Apprenticeships vs Alternative Routes

Apprenticeships aren’t the only pathway to becoming a qualified electrician in the UK. Alternatives exist, each with different trade-offs.

College-based adult learner routes:

These involve full-time or part-time study at college for Level 2 and Level 3 City & Guilds qualifications (2365 Diploma). Duration is typically 4–8 months for full-time study, or 12–18 months part-time.

Cost ranges from free (for under-19s) to £3,000–£5,000 for adults. You’ll cover the same theoretical content as apprentices but without the integrated site work. After completing classroom training, you’ll need to source work experience separately to build your NVQ portfolio and qualify for AM2S assessment.

Advantages: Faster classroom completion, flexible scheduling, suits career changers who can afford upfront costs.

Disadvantages: No guaranteed work experience, potential gap between qualification and employability, need to self-fund, doesn’t automatically lead to Gold Card (still need NVQ and AM2S).

Experienced Worker Assessment (EWA):

For people with 3–5+ years of informal electrical experience (working on sites without formal qualifications), EWA provides a route to recognition. You’ll undergo skills assessment, complete portfolio evidence for any gaps, pass 18th Edition and AM2S, then qualify for a Gold Card.

Duration: 12–18 months typically. Cost: £3,000–£6,000 depending on provider and how much additional training you need.

Advantages: Recognizes prior learning, faster than full apprenticeship, suits people who’ve been working informally.

Disadvantages: Requires proving substantial experience, still need current employment to gather portfolio evidence, not suitable for complete beginners.

Fast-track intensive courses:

These are marketed heavily but often misunderstood. They’re short courses (typically 4–8 weeks) covering specific qualifications like 18th Edition, Inspection & Testing (2391), or Level 3 Award.

Cost: £1,000–£3,000 depending on course. Duration: 4–8 weeks.

Critical limitation: These courses alone do NOT qualify you as an electrician. They provide certificates that supplement a qualification pathway, but they don’t replace the NVQ Level 3, AM2S, and site experience required for a Gold Card. Anyone selling these as “become an electrician in 6 weeks” is misleading you.

Advantages: Quick credential acquisition for specific knowledge areas, useful for qualified electricians updating skills.

Disadvantages: Often marketed deceptively, don’t lead to employment without additional NVQ/AM2S work, expensive for what they deliver.

Comparison summary:

Apprenticeships offer the most integrated pathway with guaranteed site experience and no upfront costs, but require four years and low wages throughout.

Adult college routes provide flexibility and faster classroom completion but require self-sourcing work experience and upfront fees.

EWA suits people already working informally who need formal recognition, but requires proving substantial prior experience.

Fast-track courses supplement qualifications but don’t replace formal training pathways.

None of these routes is inherently better or worse. They suit different circumstances, financial situations, and career stages. The “best” route depends on your age, financial position, existing experience, and whether you can commit to long-term low wages or prefer paying upfront for flexibility.

What Happens After You Qualify

Completing your apprenticeship, passing EPA/AM2S, and obtaining your Gold Card proves you’re a qualified electrician to industry standards. But it doesn’t immediately catapult you into high earnings or guarantee abundant job opportunities.

Early qualified period (years 1-2 post-qualification):

Newly qualified electricians still need supervision for complex work. Employers assess your competence gradually, starting you on simpler jobs and expanding responsibility as you prove reliability. Typical earnings in this period: £26,000–£32,000 annually, higher in London and the South East.

You’re building your professional reputation during these years. References matter enormously. Employers contact previous firms asking about reliability, quality of work, and ability to work independently. Strong references open doors. Poor references (or worse, no references because you’ve job-hopped constantly) limit opportunities.

Experienced electrician period (years 3-7 post-qualification):

Once you’ve demonstrated consistent competence across different job types, earning potential increases substantially. Typical ranges: £32,000–£45,000 employed, or £40,000–£70,000+ self-employed depending on location, client base, and specialization.

This is where the apprenticeship investment truly pays off. You’re now earning more than you would in most careers accessible with similar entry qualifications, and you have options: work for contractors, go self-employed, specialize in commercial/industrial sectors, or pursue additional qualifications in areas like inspection and testing.

Long-term progression:

Electricians can progress to Approved Electrician status (requires additional qualifications like 2391 Inspection & Testing), move into electrical design, become contractors themselves, or specialize in growing sectors like EV installation, solar systems, or industrial automation.

The Gold Card opens doors, but career success beyond that depends on building expertise, maintaining professional reputation, and staying current with regulation changes. BS 7671 updates regularly (most recently 18th Edition with Amendment 2 in 2022). Qualified electricians need ongoing professional development to remain current.

The realistic timeline:

Year 0-4: Apprenticeship, earning £10,000–£22,000

Year 5-6: Newly qualified, earning £26,000–£32,000

Year 7-10: Experienced electrician, earning £32,000–£45,000

Year 10+: Senior/specialized/self-employed, earning £40,000–£70,000+

This progression takes a decade from starting your apprenticeship to reaching top earnings. That’s not a criticism of the trade. It reflects the reality that genuine expertise takes time to develop, and employers pay for proven competence, not just certificates.

Electrical apprenticeships are brilliant for the right people in the right circumstances. They’re challenging or unsuitable for everyone else.

You should pursue an apprenticeship if:

You’re 16-21, living with family who can subsidize your low wages, you have four years to commit without major financial obligations, you can drive or access transport to various sites, and you prefer hands-on learning over classroom theory. If this describes you, apprenticeships offer an unbeatable combination of practical experience, recognized qualifications, and debt-free entry into a skilled trade.

You should consider alternatives if:

You’re over 25 with financial responsibilities (rent, mortgage, dependents), you need to qualify faster than four years, you have existing informal experience that could be recognized via EWA, or you can afford upfront training costs in exchange for flexible scheduling. Alternative routes exist that might better suit your circumstances.

You should definitely NOT believe claims that:

Apprenticeships are easy to secure (they’re highly competitive), you’ll earn good money immediately (you won’t, wages start very low), completion is guaranteed (roughly 50% don’t finish), or that it’s the “only proper” route (other pathways also lead to Gold Card status).

The apprenticeship model was designed for school leavers entering the workforce directly from education. It works extremely well for that demographic. Forcing it to accommodate career changers, adults with financial obligations, or people needing faster qualification timelines creates friction that often results in non-completion.

If your circumstances align with what apprenticeships offer (long-term commitment, low wages with eventual high returns, integrated learning, employer-led progression), they’re one of the best vocational training systems in the UK. If your circumstances don’t align, pursuing an apprenticeship out of belief it’s the “only legitimate” route risks wasting years in an unsustainable situation.

Be honest about your financial position, life stage, and what you can realistically commit to. The electrician trade offers multiple entry routes. Choose the one that matches your circumstances, not the one that sounds most prestigious or traditional.

Call us on 0330 822 5337 to discuss electrical qualification pathways suited to your specific circumstances. Whether you’re considering apprenticeships, adult learner routes, or experienced worker assessment, we’ll explain which options genuinely fit your age, financial situation, and career timeline. Our in-house placement team supports both apprentices needing additional site experience and adult learners transitioning from classroom to employment. No hype. No unrealistic promises. Just practical guidance on navigating UK electrical qualification routes based on where you actually are in life.

FAQs

An electrical apprenticeship combines practical site work with classroom learning. Most days are spent on-site assisting qualified electricians with tasks such as installing wiring systems, testing equipment, and maintaining electrical installations in domestic, commercial, or industrial settings.

Early work includes cable pulling, basic terminations, and tool handling. As skills develop, apprentices progress to fault-finding, commissioning, and inspection tasks under supervision. Apprentices also complete administrative work, recording evidence for their NVQ Level 3 portfolio. College attendance is typically one day per week, covering electrical theory, regulations, and calculations. The role is physically demanding, often involving confined spaces, outdoor work, and strict safety procedures.

Most electrical apprenticeships last 42 to 48 months, reflecting the requirements of the Level 3 Installation and Maintenance Electrician standard. The duration allows skills to develop progressively without compromising safety or competence.

The first year focuses on fundamentals such as safe working practices and basic installation. Later years introduce more complex systems, fault diagnosis, and maintenance tasks. Time is also required to build a comprehensive NVQ Level 3 portfolio with verified site evidence. College learning runs alongside site work throughout. End-point assessment readiness depends on portfolio completion, so delays can extend the timeline. The four-year structure reflects the complexity of electrical work and the need for consistent, supervised experience.

Electrical apprenticeships suit individuals with practical aptitude, problem-solving ability, and the discipline to commit to long-term training. They work best for school leavers or young adults with good maths and English skills, physical resilience, and family support during lower-paid early years.

They are less suitable for adults needing immediate financial stability, such as those with mortgages or dependants. The combination of low initial pay, academic requirements, and portfolio demands can be challenging. Career changers without flexibility for college attendance or supervised learning often struggle, as do those expecting quick independence. The route requires patience, structure, and sustained commitment over several years.

Apprentices are paid lower wages initially because they are learning rather than contributing fully productive labour. Employers invest in supervision, insurance, and training while absorbing lower output. Under JIB structures, early-stage pay reflects this balance, increasing as competence grows.

However, low wages contribute significantly to dropout rates, with completion around 38–39 percent. Many apprentices leave due to financial pressure, especially adults without external support. Rising living costs worsen this effect, pushing some into higher-paid unskilled work. Younger apprentices with family backing tend to complete more successfully, but overall low pay remains a major weakness in the apprenticeship pipeline.

Electrical apprenticeships are highly competitive, particularly for under-19s due to funding incentives. Employers often receive many applications and look for candidates likely to stay long-term.

Key factors include:

- GCSEs in maths and English

- Practical aptitude (work experience, DIY, technical hobbies)

- Reliability, punctuality, and attitude

- Awareness of safety and teamwork

- Physical capability for site work

A driving licence is often advantageous. While formal qualifications are not always required, enthusiasm and basic technical understanding help. Adult applicants may offset age with relevant experience, but competition generally favours younger candidates. Persistence and college links improve chances.

The balance is typically around 80 percent site work and 20 percent college learning. Most apprentices spend four days per week on-site gaining hands-on experience and one day at college studying theory.

College covers electrical science, regulations, circuit design, and calculations, while site work provides practical application. Early years focus on fundamentals at college, with more advanced topics introduced as on-site competence increases. This structure ensures theory is reinforced through real work, allowing gradual progression towards independence. The emphasis remains firmly on practical competence, reflecting the realities of the trade.

The most common reason is financial pressure caused by low early-stage pay. Many struggle to cover living costs, particularly adults without family support. The physical demands of site work, combined with academic study and portfolio requirements, also lead to burnout.

Other factors include:

- Difficulty with maths or regulations

- Poor time management for NVQ evidence

- Life changes such as family commitments

- Better-paid alternative work becoming available

- Weak employer support or unrealistic expectations

Completion rates remain low because the route is demanding and long. Those who finish tend to have strong support, resilience, and a clear understanding of the commitment involved.

The AM2S is the final practical assessment that confirms an apprentice can work safely and competently without supervision. It tests skills including safe isolation, installation, inspection, testing, and fault diagnosis under timed conditions.

It can only be attempted after gateway approval, which confirms the NVQ Level 3 portfolio and qualifications are complete. Passing the AM2S allows application for the ECS Gold Card. The assessment ensures consistent national standards and acts as the transition from trainee to qualified electrician. Retakes are possible if sections are failed, but preparation is essential.

An apprenticeship offers structured training, paid employment, and integrated experience leading directly to NVQ Level 3 and Gold Card eligibility. It suits those able to commit long-term despite low initial wages.

Adult learner courses (e.g. Level 2 and 3 diplomas) offer flexibility for career changers but require separate site experience, NVQ assessment, and end-point testing, often self-funded. The Experienced Worker Assessment (EWA) suits those with significant prior experience, allowing faster progression through portfolio evidence and assessment without repeating training.

Apprenticeships provide the most rounded development but take the longest. Alternative routes demand more self-direction and carry higher financial risk but can be quicker for experienced adults.

References

- Institute for Apprenticeships: Installation & Maintenance Electrician Standard – https://www.instituteforapprenticeships.org/apprenticeship-standards/installation-electrician-and-maintenance-electrician-v1-2

- GOV.UK: Become an Apprentice – https://www.gov.uk/become-apprentice

- GOV.UK: Apprenticeship Pay and Conditions – https://www.gov.uk/become-apprentice/pay-and-conditions

- JIB: Apprentice Rates 2025 – https://www.jib.org.uk/news/jib-apprentice-rates-2025

- National Careers Service: Electrician Profile – https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/job-profiles/electrician

- GOV.UK: Apprenticeship Funding Rules – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeship-funding-rules

- Builders Merchants News: Apprenticeship Decline Report – https://www.buildersmerchantsnews.co.uk/Report-identifies-apprenticeship-decline-in-construction/59517

- Dart Tool Group: The Apprenticeship Gap 2025 – https://www.darttoolgroup.com/the-apprenticeship-gap-2025

- Electrical Times: Apprenticeship Shortfall Article – https://www.electricaltimes.co.uk/apprenticeship-shortfall-of-nearly-10000-threatens-uk-electrical-sector

- NICEIC: Electrotechnical Skills Shortage – https://niceic.com/views/the-electrotechnical-skills-shortage

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 09 February 2026. This article is maintained and updated as apprenticeship standards, JIB wage rates, and government funding rules change. Pay rates reflect 2026 JIB agreements. Completion statistics based on most recent ONS and construction sector reports. For current apprenticeship vacancies and specific employer requirements, check GOV.UK’s Find an Apprenticeship service and contact training providers directly.