The History of Solar PV: From 1839 Discovery to UK’s 21.5 GW Network

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Updated 2025 UK capacity data to 21.5 GW; added record installation figures

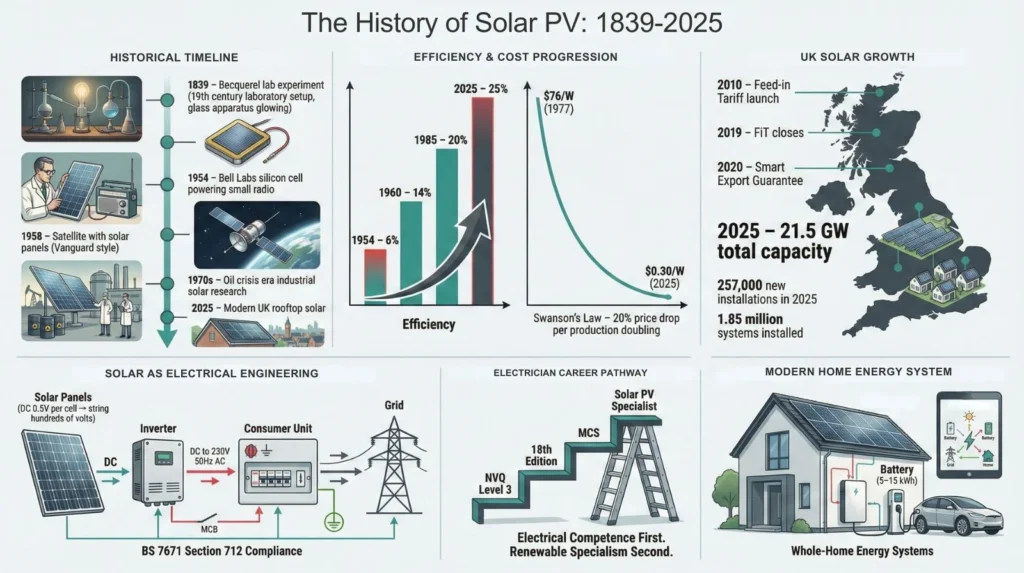

The photovoltaic effect was discovered in 1839, but it took over a century before Bell Labs created practical silicon cells in 1954. This history matters for electricians because it reminds us that solar PV is fundamentally electrical engineering applying established DC and AC principles, not mysterious new technology.

The 2025 record of 257,000 new solar installations represents substantial opportunity for electricians with proper qualifications. Employers report the main barrier isn’t finding workers, it’s finding workers with both electrical competence and renewable energy knowledge. That combination commands premium rates.

When the Photovoltaic Effect Was Actually Discovered

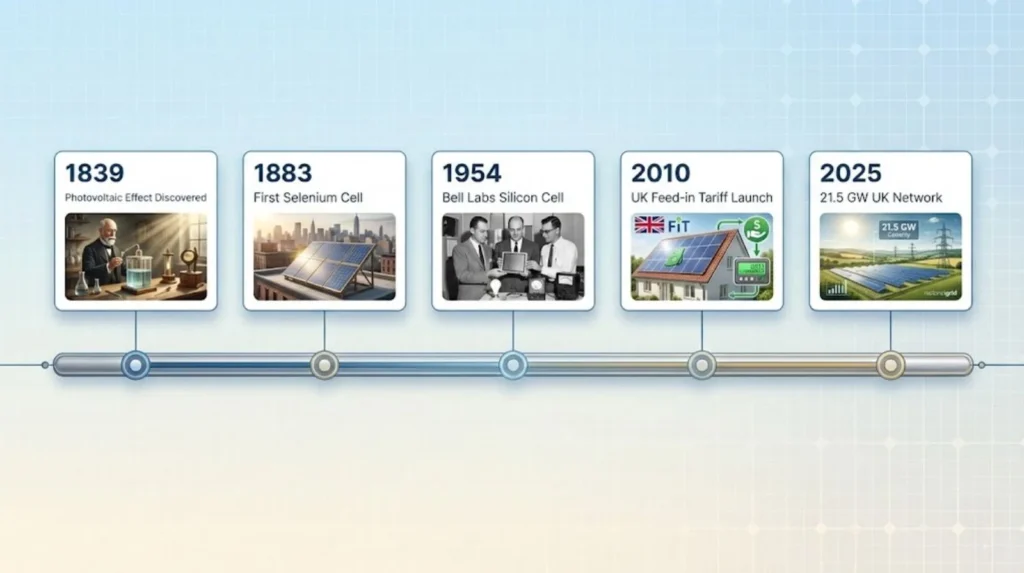

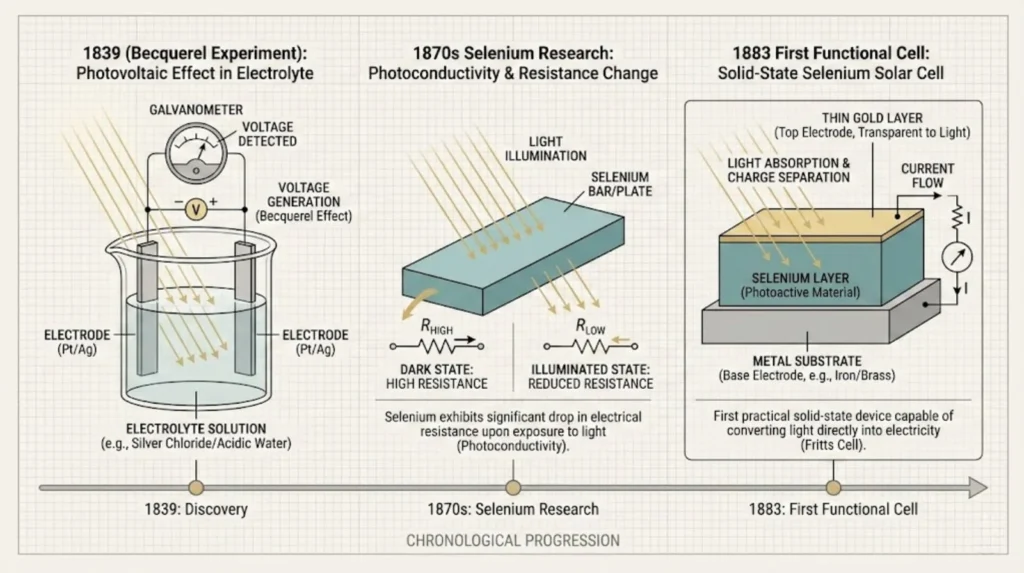

French physicist Edmond Becquerel was 19 years old in 1839 when he observed voltage generation from light exposure during an electrolyte experiment. This wasn’t a power source, it was a laboratory curiosity with minuscule efficiency.

By the 1870s, selenium became the focus. Willoughby Smith noted in 1873 that light altered selenium’s electrical resistance. William Grylls Adams and Richard Evans Day demonstrated electricity generation from sunlight in 1876. Charles Fritts created the first functional cell in 1883, selenium coated with gold, achieving roughly 1% efficiency.

Early limitations were stark. Materials degraded quickly, costs were prohibitive (hundreds of dollars per watt equivalent in today’s terms), and output was too low for anything beyond demonstrations. Commercial viability was impossible without semiconductors that could efficiently separate electrical charges.

"According to MCS standards, installers need demonstrated electrical competence before adding solar-specific training. The 18th Edition and NVQ Level 3 come first, then specialist PV courses build on that foundation."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

The 1954 Bell Labs Breakthrough That Changed Everything

Russell Ohl patented the silicon p-n junction in 1941, creating a diode sensitive to light. At Bell Labs, Daryl Chapin, Calvin Fuller, and Gerald Pearson refined it. On 25 April 1954, they unveiled the first practical silicon cell at 6% efficiency, enough to power a radio and toy windmill.

This was the genuine breakthrough. Selenium cells had proven the physics, silicon cells proved the engineering potential.

NASA’s Vanguard I satellite launched in 1958 using six silicon cells producing 1W total, proving reliability in vacuum conditions. By 1960, Hoffman Electronics achieved 14% efficiency. Space exploration demand drove research and development investment, but terrestrial use lagged due to cost. The price per watt was still over $1,000 in 1950s money.

The 1970s oil crises triggered government interest in alternative energy. Dr. Elliot Berman, backed by Exxon, designed cheaper solar cells by using lower grade silicon and different packaging. Costs dropped from $100 per watt to roughly $20 per watt by the mid-1970s. Still expensive, but the trajectory was established.

How Manufacturing Scale Crashed Solar Costs

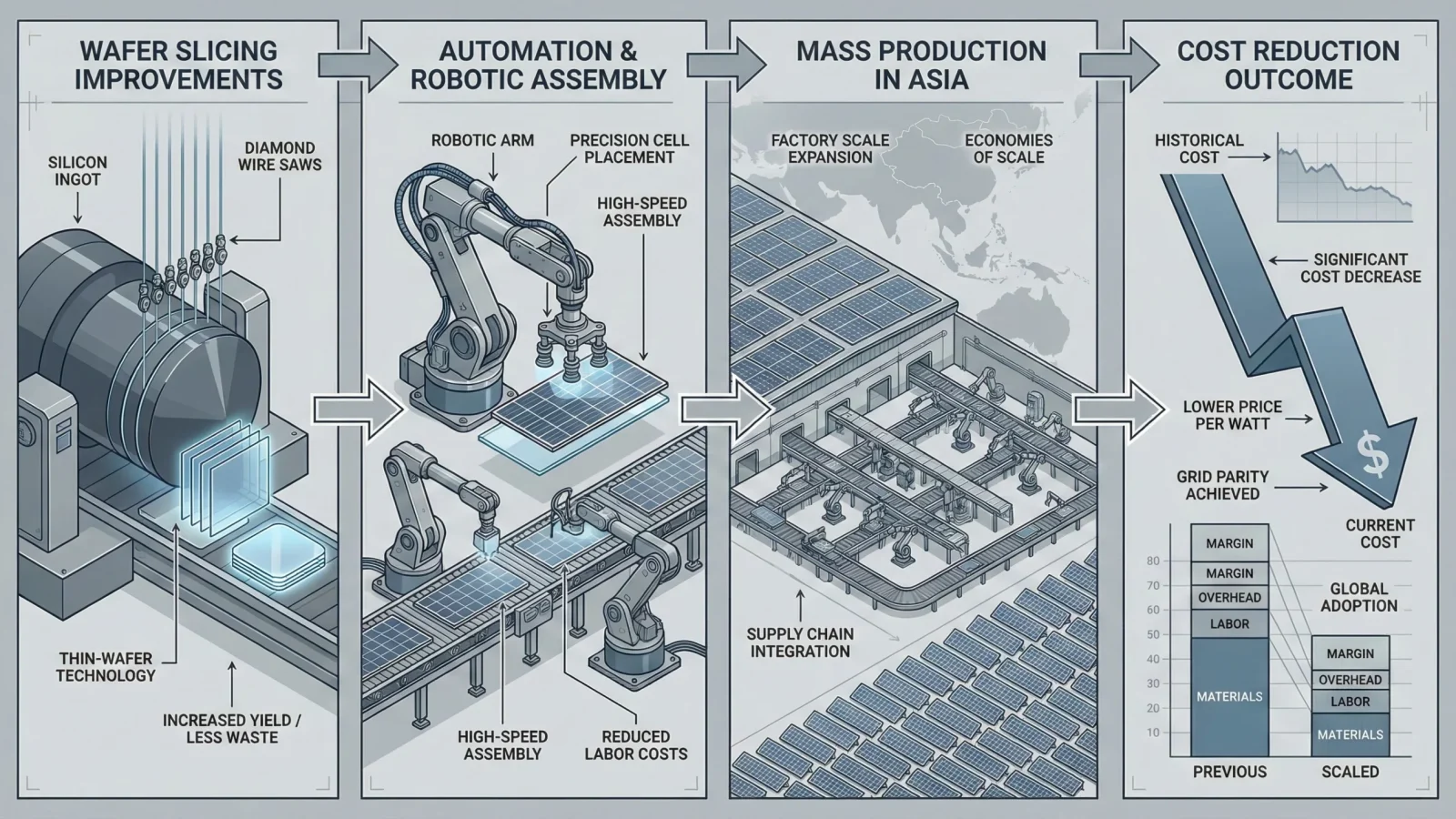

The “learning curve” of solar PV is one of the most dramatic in industrial history. For every doubling of cumulative installed capacity, module prices fell roughly 20%. This is Swanson’s law in action.

Module costs dropped from $76 per watt in 1977 to $0.36 per watt by 2014, now sitting around $0.20 to $0.30 per watt. Global capacity grew from gigawatt scale in 2000 to terawatt scale by 2024, halving costs every four to five years.

This wasn’t hype or subsidy magic. This was manufacturing automation, wafer slicing improvements, and production scale concentrated primarily in Asia. China’s entry into solar manufacturing in the 2000s scaled production exponentially.

UK grid parity, where solar generation costs equal or beat grid electricity costs, arrived around 2015 for rooftop systems. By 2020, solar PV became the cheapest new electricity source in many markets according to IEA data. Not the cheapest “renewable” source, the cheapest source full stop in sunny regions.

For electricians, this cost collapse created a genuine career pathway. What was niche specialist work in 2010 is now standard domestic and commercial installation work in 2025.

UK Solar Growth From 2010 FiT Launch to 2025 Record

The UK solar market was marginal until the Feed-in Tariff launched in April 2010. Payments up to 43p per kWh for generation plus export payments triggered explosive growth. Installations jumped from 24,000 systems in 2010 to 838,000 by 2015. Capacity grew from under 100 MW to roughly 5 GW in the same period.

The government cut tariff rates repeatedly between 2011 and 2012 to manage budget exposure, creating boom and bust cycles. Installers either adapted quickly or went under. The FiT closed to new applicants in March 2019 after approximately 870,000 systems had been registered.

The Smart Export Guarantee launched in January 2020, shifting the focus entirely. SEG is not a subsidy, it’s a market mechanism. Energy suppliers must pay for exported electricity, but rates vary from 4.1p per kWh fixed deals to 17.5p per kWh premium tariffs. There’s no generation payment like FiT offered. The emphasis moved to self-consumption, using solar power on-site rather than exporting it.

By late 2025, UK solar capacity reached 21.5 GW total. Roughly 38% is ground-mount solar farms, the rest is distributed across rooftops. Over 1.85 million MCS-certified systems are operational. The 2025 record of 257,000 new installations represents the strongest year for rooftop solar since FiT’s peak years.

Domestic uptake now exceeds 1.6 million homes, boosted by new build standards and battery storage pairings. Policy evolved from FiT’s volume driver approach to SEG’s market signal approach, reflecting Net Zero priorities. DESNZ data shows 32% generation growth in H1 2025 compared to H1 2024.

"What we're seeing at the moment is strong demand for qualified electricians willing to move into solar. Placements in the renewable sector are growing, but firms still want traditional electrical competence first."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

To be fair, the shift from guaranteed income to variable export payments changed the installer conversation entirely. Battery storage became essential for maximizing returns rather than optional luxury. Time-of-use tariffs like Octopus Agile allow systems to interact with grid pricing, charging batteries when electricity is cheap or even negative priced, exporting when prices peak.

For common questions about how solar fits into UK electrical qualifications, the answer is consistent. Foundation electrical competence comes first, renewable specialisms build on that base.

Why Solar PV is Electrical Engineering, Not Magic Panels

Here’s the thing about solar that gets missed in marketing materials. PV cells produce DC at low voltage, roughly 0.5V per cell. These are aggregated into strings producing hundreds of volts for inversion to 230V/50Hz AC. This is electrical systems integration work.

Inverters handle DC to AC conversion, grid synchronisation, and safety features including rapid shutdown and anti-islanding protection. Protection requirements include overcurrent devices, earth fault monitoring, and isolation switching per BS 7671 Section 712 covering array wiring, DC isolators, and AC connections.

UK installers navigate MCS certification for system quality assurance alongside electrical competence requirements like 18th Edition knowledge and Part P compliance. The distinction matters. MCS ensures product and installation quality, electrical regulations govern the power system integration.

As systems become more complex with multi-string arrays, hybrid inverters, and battery integration, electrical expertise prevents faults that marketing brochures won’t mention. DC arcing, voltage drop calculations, string configuration, earth bonding, and consumer unit integration all require genuine electrical knowledge.

The complete training pathway for solar work reflects this reality. NVQ Level 3, 18th Edition, then specialist PV training, then practical experience. Shortcuts don’t produce competent installers, they produce callbacks and safety issues.

What Modern Solar Systems Actually Include

The modern UK installer quote rarely covers “just solar” anymore. The industry moved to whole-home energy systems.

Battery storage appears in most new domestic quotes. Capturing daytime generation for evening use makes financial sense when export payments are low and grid electricity costs are high. Energy Storage Systems typically offer 5 to 15 kWh capacity, enough for overnight consumption.

EV integration connects solar inverters to charge points, ensuring vehicles charge with self-generated electricity rather than grid power. This appeals to environmental concerns and reduces running costs.

Smart controls via apps allow remote monitoring, performance tracking, and system optimization. Fault detection alerts notify installers before customers notice issues. Consumption data helps households shift usage to solar generation periods.

Agrivoltaics and floating arrays represent emerging installation types, though domestic and commercial rooftop work remains the volume market for most installers.

Complexity signals opportunity. From 4kW domestic systems to 100kW commercial arrays, installations demand electrical oversight for safety, performance, and grid compliance. This isn’t DIY territory, it’s skilled trade work with genuine career progression potential.

Myths That Waste Everyone's Time

“Solar is recent, unproven technology”

The photovoltaic effect was observed in 1839. Silicon cells have been in continuous space and terrestrial use since 1954. Modern panels build on 70 years of refinement, not novelty. The physics is established, the engineering is mature.

“Panels alone make a system work”

A PV array produces DC electricity. Requires inverters, cabling, protection devices, metering, and grid connection infrastructure. Poor integration causes 20 to 30% underperformance in UK installations according to industry fault data. The panels are one component, not the complete system.

“FiT and SEG are identical”

Feed-in Tariff paid fixed rates for all generation plus exports, closed 2019. Smart Export Guarantee pays variable rates for exports only, launched 2020. FiT legacy systems continue receiving payments, new systems use SEG. The economics are completely different.

“Solar removes the need for electrical expertise”

DC hazards, high voltages, and grid interaction requirements demand qualified electricians. MCS complements Part P skills, doesn’t replace them. As battery storage and hybrid systems become standard, electrical competence becomes more critical, not less.

What This History Means for Electricians in 2026

Solar PV evolved from laboratory curiosity to UK grid asset over 185 years. The journey from 1% selenium efficiency to 25% silicon efficiency, from $76 per watt to $0.30 per watt, and from negligible UK capacity to 21.5 GW demonstrates engineering progress, not marketing hype.

For electricians, this history underscores solar’s integration into distributed generation networks as DC-to-AC electrical systems demanding rigorous installation standards. The 257,000 new systems installed in 2025 represent genuine employment opportunity, but only for those with foundation electrical qualifications before specialist solar training.

The policy shift from FiT subsidy to SEG market mechanism changed installer business models. Battery storage, EV integration, and smart controls increased system complexity. This demands deeper electrical knowledge, not less.

Employers in the renewable sector consistently report the skills gap isn’t finding people interested in solar work, it’s finding electrically competent people willing to add solar specialisms. That gap represents your career opportunity if you approach it with proper qualifications rather than shortcuts.

If you’re considering electrician training in Hereford or anywhere across the UK with the goal of moving into renewable energy work, the qualification pathway is clear. Foundation electrical training establishes competence in AC systems, consumer units, protection devices, and BS 7671 compliance. Solar-specific training then builds on that base with DC string configuration, inverter selection, MCS standards, and system commissioning.

Call us on 0330 822 5337 to discuss the fastest route from electrical foundation training to qualified renewable energy work. We’ll explain exactly what qualifications employers actually look for, realistic timelines, and what our in-house recruitment team does to secure placements with contractors installing solar systems. No hype, no unrealistic promises, just practical guidance from people who’ve placed hundreds of learners with UK employers.

FAQs

What did Edmond Becquerel actually discover in 1839, and why wasn’t it useful as a power source at the time?

In 1839, French physicist Edmond Becquerel discovered the photovoltaic effect, observing that certain materials, such as silver chloride in an acidic solution connected to platinum electrodes, generated a small electric current when exposed to light. This marked the first observation of light directly producing electricity in a solid-state setup. However, the voltages and currents were minuscule, with efficiencies far below 0.1 per cent, making it impractical for meaningful power generation and limiting it to laboratory demonstrations.

How did selenium experiments in the 1870s and 1880s move solar PV from “interesting physics” toward a functioning cell?

In 1873, Willoughby Smith identified the photoconductivity of selenium, showing it became more conductive under light. This led to William Grylls Adams and Richard Evans Day’s 1876 experiments, where selenium bars produced electricity directly from sunlight without heat or mechanical parts. By 1883, Charles Fritts had built the first solid-state photovoltaic cell using a selenium layer coated with gold, achieving around 1 per cent efficiency and demonstrating a workable, if rudimentary, device.

Why was the 1954 Bell Labs silicon cell the first truly practical photovoltaic breakthrough?

Developed by Daryl Chapin, Calvin Fuller, and Gerald Pearson at Bell Labs, the silicon cell achieved 6 per cent efficiency, far surpassing earlier selenium devices, and reliably powered small loads such as a toy Ferris wheel and a radio transmitter. Silicon’s abundance, stability, and compatibility with semiconductor manufacturing enabled scalable production, shifting photovoltaic technology from niche experiments to a technology with genuine commercial potential.

What role did early space missions like Vanguard I play in proving solar PV reliability and accelerating development?

Launched in 1958, Vanguard I was the first satellite to use solar cells for primary power, operating reliably for over six years despite the harsh space environment. This demonstrated PV’s durability and low maintenance, spurring US government and industry investment in space-qualified cells. The resulting improvements in efficiency, radiation resistance and manufacturing laid the foundation for terrestrial applications.

How did the oil crises and 1970s industrial research change the cost and manufacturability of solar cells?

The 1973 and 1979 oil crises prompted governments and energy firms to fund photovoltaic research and development as an alternative to fossil fuels, with the United States allocating billions to research. Efficiency doubled through advances in silicon processing, while industrial efforts led by companies such as Exxon and Mobil improved crystal growth, doping, and module assembly. These changes reduced costs from over $100 per watt in the early 1970s to around $10 by the end of the decade, making solar cells more manufacturable.

What is Swanson’s Law, and how did manufacturing scale drive module prices down so sharply over time?

Named after SunPower founder Richard Swanson, Swanson’s Law observes that solar PV module prices fall by about 20 per cent for every doubling of cumulative global production volume. This learning curve effect stems from manufacturing efficiencies, including automation, larger wafers, thinner cells, supply chain optimisation, and ongoing process refinements. Over several decades, production scaling from megawatts in the 1970s to terawatts today has driven prices down by a factor of more than 500.

How did the UK Feed-in Tariff (2010) reshape solar adoption, and what were the main reasons for the boom and bust cycles?

Introduced in April 2010, the Feed-in Tariff offered generous fixed payments of up to 41p per kWh for generated electricity, spurring a boom that installed over 800,000 systems by 2015 and grew the UK solar fleet from near zero to gigawatt scale. Degressions and caps, driven by scheme costs exceeding budgets, halved rates in 2011–12, causing a bust as installations plummeted and the supply chain contracted. This cycle highlighted the need for predictable policy to sustain deployment.

What changed when the UK moved from the Feed-in Tariff to the Smart Export Guarantee, and how did that shift household economics?

The Feed-in Tariff closed to new applicants in 2019 and was replaced by the Smart Export Guarantee in 2020, which pays only for exported electricity at market-driven rates, typically 5 to 20 pence per kWh depending on the supplier, rather than providing a fixed generation tariff. Without subsidies for self-generated power, the economics now depend on maximising on-site consumption, often through the use of batteries, to offset electricity bills. This makes photovoltaic systems more viable for households with high daytime demand but less attractive for those relying primarily on export income.

What does a “21.5 GW UK solar network” actually represent in practical terms, and how is capacity split between rooftop and ground-mount?

The 21.5 GW figure, as of late 2025, represents the UK’s total installed solar PV capacity and generates around 20 TWh annually, which is enough to meet the electricity needs of over 6 million homes under typical UK conditions with a capacity factor of about 10 to 11 per cent. Capacity is split at roughly 42 per cent rooftop, including domestic and commercial systems, and 58 per cent ground-mounted installations, with the latter dominated by large utility-scale solar farms connected to the grid.

Why does the history of PV matter for electricians today, particularly regarding DC-to-AC integration, BS 7671 Section 712, and MCS expectations?

PV’s evolution from early low-power cells to grid-scale arrays underscores the critical need for safe DC to AC integration, with inverters handling high-voltage DC arrays feeding the AC network. BS 7671 Section 712 sets requirements for PV-specific earthing, protection and array wiring to mitigate risks like arc faults, while MCS certification ensures installers meet these standards for consumer protection and scheme eligibility. Understanding this history reinforces why rigorous, standards-driven practice is essential for reliable, compliant UK installations.

References

- Timeline of solar cells – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_solar_cells

- UK Government solar PV deployment statistics – https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/solar-photovoltaics-deployment

- PV Magazine UK 2025 capacity data – https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/12/19/uk-added-at-least-2-5-gw-solar-in-2025-revised-data-reveals/

- Solar Energy UK Smart Export Guarantee guide – https://solarenergyuk.org/resource/smart-export-guarantee/

- Ofgem SEG information – https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/environmental-and-social-schemes/smart-export-guarantee-seg

- MCS UK rooftop installation records – https://mcscertified.com/uk-rooftop-solar-installations-hit-record-high/

- IEA PVPS trends 2025 – https://iea-pvps.org/trends_reports/trends-2025/

- Swanson’s law explanation – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swanson%27s_law

- Bell Labs silicon solar cell history – https://www.aps.org/apsnews/2009/04/bell-labs-silicon-solar-cell

- Energy Sage solar history – https://www.energysage.com/about-clean-energy/solar/the-history-and-invention-of-solar-panel-technology/

- Sunsave UK solar statistics – https://www.sunsave.energy/solar-panels-advice/solar-energy/statistics

- Parliament Commons Library solar briefing – https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7434/

- Renew Solar BS 7671 Section 712 guide – https://www.renewsolar.co.uk/uncategorised/delving-into-bs-7671-section-712-and-solar-panel-systems/

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 19 February 2026. This page is maintained and we correct errors and refresh sources as standards, regulations, and UK solar deployment data change. Historical efficiency data varies between laboratory cell records and commercial module averages. UK deployment statistics from 2010 to 2015 are highly accurate due to FiT registration requirements. Post-2019 data for unsubsidised installations can be slightly more fragmented though DESNZ maintains robust records.