Why Electric Vehicles Weigh 30% More Than Petrol Cars (And What It Means for Parking, Roads, and Infrastructure)

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Initial publication addressing EV weight reality, car park safety concerns, and infrastructure implications across English-speaking countries

Electric vehicles are approximately 20-30% heavier than their petrol or diesel equivalents. A Tesla Model 3 weighs 1,847 kg / 4,072 lbs compared to a similar-sized BMW 3 Series at 1,540 kg / 3,395 lbs. A Ford F-150 Lightning electric pickup weighs 2,726 kg / 6,015 lbs while its petrol version weighs 1,950 kg / 4,300 lbs.

This weight difference has created questions about whether electric vehicles are too heavy for multi-storey car parks, whether roads can handle the additional mass, and what this means for infrastructure planning in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, and other English-speaking countries.

The short answer: modern parking structures are designed for vehicles weighing up to 3,000 kg / 6,614 lbs with substantial safety margins. The real infrastructure challenge isn’t structural capacity in most cases but rather ensuring adequate charging infrastructure exists to support the transition to electric mobility.

This matters because misunderstanding EV weight impacts creates two problems: unnecessary panic about structural safety, and insufficient focus on the actual infrastructure gap which is charging point installation and electrical capacity upgrades.

How Much Heavier Are Electric Vehicles Actually?

The weight difference varies by vehicle size and design, but patterns are consistent across markets:

Small electric hatchbacks add 200-300 kg / 440-660 lbs compared to petrol equivalents. A Nissan Leaf weighs 1,685 kg / 3,714 lbs while a similar-sized petrol hatch weighs around 1,350 kg / 2,976 lbs.

Family sedans and medium SUVs show 300-400 kg / 660-880 lbs increases. The Tesla Model 3 at 1,847 kg / 4,072 lbs compares to the BMW 3 Series at 1,540 kg / 3,395 lbs, a difference of 307 kg / 677 lbs or approximately 20%.

Large SUVs and trucks demonstrate the most dramatic differences. The Ford F-150 Lightning weighs 2,726 kg / 6,015 lbs compared to the standard F-150’s 1,950 kg / 4,300 lbs, adding 776 kg / 1,715 lbs or nearly 40% additional mass.

These aren’t theoretical calculations. These are kerb weights (curb weights in US terminology) taken from manufacturer specifications, representing the vehicle’s weight with all fluids but no passengers or cargo.

Why the percentage matters more than absolute weight:

A 300 kg / 660 lb increase sounds substantial in isolation. But modern parking structures in the UK, US, Canada, and Australia are designed for distributed loads assuming vehicles up to 2,500-3,000 kg / 5,512-6,614 lbs. Many petrol SUVs already exceed 2,200 kg / 4,850 lbs without creating structural concerns.

The weight increase from electrification isn’t introducing a new category of vehicle mass. It’s moving more vehicles into weight ranges that petrol SUVs and commercial vehicles have occupied for decades. Parking structures designed in the 1990s accommodated delivery vans weighing 3,000+ kg / 6,614+ lbs. Modern electric family cars at 2,000 kg / 4,409 lbs don’t exceed those original design parameters.

Weight Comparison Table (Metric / Imperial)

| Vehicle Type | Typical Petrol Weight | Typical EV Weight | Difference |

| Small Hatchback | 1,200-1,400 kg / 2,646-3,086 lbs | 1,500-1,800 kg / 3,307-3,968 lbs | 20-25% heavier |

| Family Sedan | 1,500-1,700 kg / 3,307-3,748 lbs | 1,800-2,200 kg / 3,968-4,850 lbs | 15-20% heavier |

| Large SUV | 2,100-2,500 kg / 4,630-5,512 lbs | 2,500-3,200 kg / 5,512-7,055 lbs | 10-20% heavier |

| Pickup Truck | 1,950-2,400 kg / 4,300-5,291 lbs | 2,700-3,400 kg / 5,953-7,496 lbs | 30-40% heavier |

The percentage increase is highest in smaller vehicles where battery packs represent a larger proportion of total mass. It narrows in larger vehicles because petrol versions are already heavy from larger engines, reinforced frames, and four-wheel-drive systems.

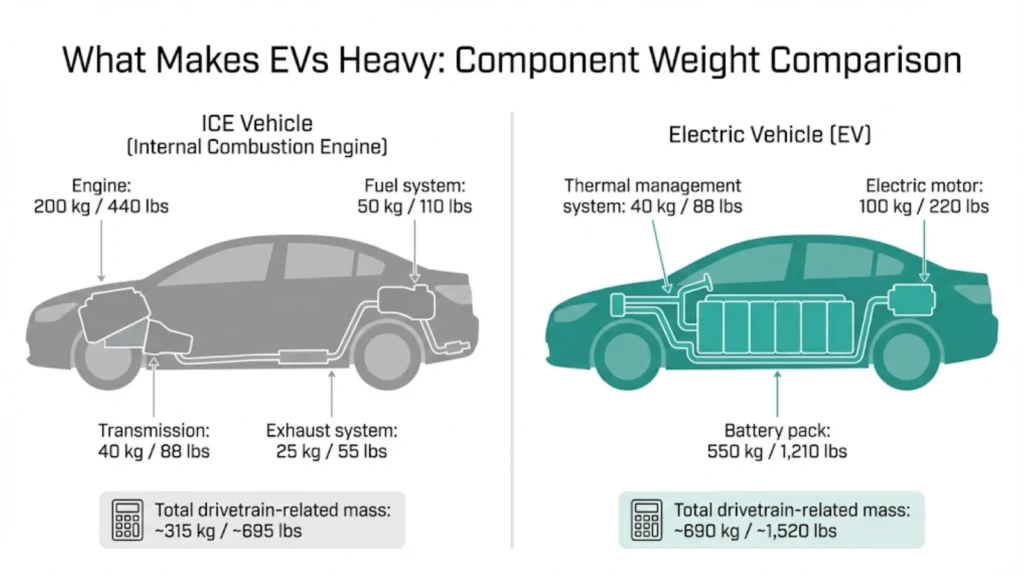

What Makes Electric Vehicles So Heavy?

The weight increase stems from three primary factors: battery pack mass, structural reinforcement to support that battery, and safety systems protecting high-voltage components.

Battery packs are the dominant weight contributor

Lithium-ion battery packs used in electric vehicles weigh approximately 5-7 kg per kilowatt-hour / 11-15 lbs per kWh of capacity. A 60 kWh battery pack weighs 360-420 kg / 794-926 lbs. A 100 kWh pack weighs 600-700 kg / 1,323-1,543 lbs.

For context, a typical petrol engine and fuel system (engine block, gearbox, exhaust, full fuel tank) weighs approximately 250-350 kg / 551-772 lbs in a family sedan. An electric motor and single-speed transmission weighs roughly 100-150 kg / 220-331 lbs.

The net addition from replacing a complete petrol powertrain with an electric one is approximately 200-400 kg / 440-880 lbs in most vehicles, depending on battery size.

Structural reinforcement adds secondary weight

Battery packs must be protected from impact damage to prevent thermal runaway fires. This requires reinforced underbody structures with crash-resistant casing, typically adding 50-100 kg / 110-220 lbs beyond the battery cells themselves.

The additional vehicle mass requires stronger suspension components, larger brake systems, and reinforced chassis mounting points. Each heavier component cascades: heavier brakes need stronger mounting brackets, which need stronger frame sections, which add mass requiring further reinforcement.

Engineers estimate that for every 3 kg / 6.6 lbs of battery weight added, approximately 1 kg / 2.2 lbs of structural reinforcement is required elsewhere in the vehicle. This “weight compounding effect” means a 450 kg / 992 lb battery pack creates approximately 600 kg / 1,323 lbs of total additional vehicle mass.

Safety systems and thermal management

High-voltage electrical systems require additional safety isolation, protective covers, and emergency disconnect systems. Battery thermal management systems (cooling pumps, radiators, piping, and control electronics) add 30-60 kg / 66-132 lbs.

Modern electric vehicles include battery fire suppression systems, high-voltage disconnect mechanisms accessible to emergency responders, and reinforced door structures to protect battery cables running through the cabin floor. These safety additions collectively add 40-80 kg / 88-176 lbs.

What electric vehicles remove

Electric vehicles eliminate several heavy components: traditional gearboxes (25-40 kg / 55-88 lbs), exhaust systems with catalytic converters (15-30 kg / 33-66 lbs), complex engine cooling systems (20-35 kg / 44-77 lbs), and fuel tanks with pumps and lines (15-25 kg / 33-55 lbs when full).

The total weight saving from eliminated components is approximately 100-150 kg / 220-331 lbs, which partially offsets but doesn’t eliminate the battery weight penalty.

Body-in-white and chassis weight optimization

“Body-in-white” refers to the vehicle’s structural shell before paint, trim, or mechanical components are added. In petrol vehicles, this typically weighs 350-450 kg / 772-992 lbs for a family sedan using primarily steel construction.

Electric vehicle manufacturers increasingly use aluminum or mixed-material body-in-white construction to reduce structural weight. An aluminum-intensive BIW weighs 280-380 kg / 617-838 lbs, saving 70-100 kg / 154-220 lbs compared to steel equivalents.

The chassis or platform (the structural underbody) in many electric vehicles uses “skateboard” architecture where the battery pack forms part of the structural floor. This integrates the battery housing with the chassis, eliminating redundant structure and saving 30-50 kg / 66-110 lbs compared to mounting a battery pack in a traditional chassis design.

Despite these optimizations, the net result is still a heavier vehicle. A petrol sedan with 400 kg BIW and 250 kg powertrain totals 650 kg / 1,433 lbs for these components. An electric equivalent with 320 kg BIW, 150 kg motor/transmission, and 550 kg battery pack totals 1,020 kg / 2,249 lbs, an increase of 370 kg / 816 lbs.

The Car Park Safety Question: Are EVs Too Heavy for Multi-Storey Parking?

This question has generated significant media attention, particularly following parking structure incidents in New York City and speculation about aging UK car parks. The technical reality is more nuanced than headlines suggest.

What parking structures are actually designed for

Modern multi-storey car parks in the UK are designed to Eurocode standards recommending distributed loads of 2.5-3.0 kN/m² (kilonewtons per square meter), equivalent to vehicles weighing 2,500-3,000 kg / 5,512-6,614 lbs spread across typical parking bay dimensions.

US parking garages follow ASCE 7 standards specifying 40 psf (pounds per square foot) for passenger vehicles up to 4,536 kg / 10,000 lbs. Canadian and Australian standards follow similar principles with minor regional variations.

These design standards don’t specify “this structure is safe for vehicles up to exactly 2,000 kg.” They specify distributed loads across the entire floor slab, assuming a realistic mix of vehicles from small hatchbacks to large SUVs filling parking spaces.

Engineers apply safety factors of 1.5-2.0 times the expected load. A structure designed for 2.5 kN/m² distributed load has actual capacity of 3.75-5.0 kN/m² before failure mechanisms activate. Electric vehicles weighing 1,800-2,200 kg / 3,968-4,850 lbs don’t approach these safety limits.

Weight distribution matters more than total mass

A vehicle’s weight is distributed across four tire contact patches, each approximately 15 cm × 20 cm / 6 in × 8 in. A 2,000 kg / 4,409 lb vehicle creates approximately 500 kg / 1,102 lbs per wheel, or 16.7 kg/cm² / 238 psi contact pressure.

Electric vehicles often achieve more balanced 50/50 front-rear weight distribution because battery packs sit low in the center of the vehicle. Petrol vehicles are typically front-heavy (60/40 or 65/35 distribution) with engine weight concentrated over the front axle.

More balanced weight distribution in electric vehicles can actually reduce point loading stress on parking structure slabs compared to equivalent-mass petrol vehicles with concentrated front-axle loading.

The real structural risks aren’t about new EVs

Parking structure failures stem from cumulative factors: aging concrete, water infiltration causing rebar corrosion, poor maintenance, exceeding design capacity with too many vehicles, and heavy commercial vehicles exceeding design assumptions.

The 2023 Ann Street parking garage collapse in New York City prompted widespread speculation about electric vehicle weights. Investigations found structural deterioration, not electric vehicles, as the primary failure cause. The structure had existed for decades serving petrol vehicles, many of which (SUVs, commercial vans) exceeded the weight of typical electric cars.

Wolverhampton car park collapse in 1997 in the UK occurred long before electric vehicle adoption. The cause was concrete deterioration and inadequate maintenance.

Documented parking structure failures attributable specifically to electric vehicle weights: zero. Documented failures attributable to aging infrastructure, deferred maintenance, and structural deterioration: dozens globally over past decades.

Where legitimate concerns exist

Older parking structures built before 1980 using outdated design standards may have lower load capacity assumptions based on 1970s vehicle weights (typical family car: 1,000-1,200 kg / 2,205-2,646 lbs). Modern vehicles of any propulsion type exceed these assumptions.

Very heavy electric vehicles like the GMC Hummer EV at 4,111 kg / 9,063 lbs or Rivian R1T at 3,270 kg / 7,209 lbs push toward the upper limits of passenger vehicle design categories. Parking structures designed assuming typical vehicle weights of 1,500-2,000 kg / 3,307-4,409 lbs may not have adequate safety margins for numerous 3,000+ kg / 6,614+ lb vehicles parking simultaneously on one level.

Concentrated loading scenarios where an entire parking level fills with heavy electric SUVs could theoretically exceed design assumptions if the structure was already marginally compliant or deteriorated. But this scenario requires: 1) every parking space filled, 2) every vehicle being heavy EV variant, 3) structure already near capacity limits. This combination is statistically rare.

"The debate about whether EVs are too heavy for car parks misses the actual infrastructure challenge. Car parks in the UK, US, Canada and Australia are designed for lorries and SUVs exceeding 3,000 kg / 6,614 lbs. The real issue is installing adequate charging points to meet demand, which requires electricians who understand load balancing across multiple charge points."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

This highlights the actual infrastructure challenge: it’s not whether car parks can support electric vehicle weight, but whether electrical infrastructure can support charging demand. Installing car park charging points requires EV charging installation training for electricians to handle load calculations, distribution board upgrades, and charge point commissioning across dozens or hundreds of parking bays.

What About Roads, Bridges, and Other Infrastructure?

The car park safety question extends to broader infrastructure concerns: do heavier electric vehicles cause more road damage, bridge stress, or accelerated infrastructure deterioration?

Road wear and the “fourth power law”

Road damage increases exponentially with vehicle weight according to the fourth power law: doubling a vehicle’s weight creates 16 times more road surface damage (2^4 = 16). A 2,000 kg / 4,409 lb vehicle causes 16 times more damage than a 1,000 kg / 2,205 lb vehicle.

But the law applies to axle loads, not total vehicle weight. A 2,000 kg EV with weight distributed across two axles creates 1,000 kg / 2,205 lbs per axle. A 1,600 kg petrol car with front-heavy weight distribution might have 1,000 kg / 2,205 lbs on the front axle alone.

More importantly, passenger vehicles cause negligible road damage compared to heavy goods vehicles. A single 40-tonne / 88,185 lb articulated lorry causes more road surface damage than 10,000 passenger cars regardless of whether those cars are electric or petrol-powered.

Highway engineers don’t design road surfaces based on passenger car weights. They design for heavy commercial vehicle traffic. The weight difference between petrol and electric passenger cars is irrelevant to road engineering calculations dominated by HGV loads.

Bridge load ratings

UK bridges carry load rating signs indicating maximum gross vehicle weight, typically 7.5-44 tonnes / 16,535-97,003 lbs for different bridge categories. US bridge ratings follow similar principles.

A heavy electric SUV at 2,800 kg / 6,173 lbs represents 3.7% of the minimum bridge load rating. Adding 500 kg / 1,102 lbs to make it electric instead of petrol increases the ratio to 4.4%. Both fall far below structural capacity limits.

Historic bridges with weight restrictions (common in the UK and Europe) restrict vehicles above certain gross vehicle weight ratings, typically 3.5-7.5 tonnes / 7,716-16,535 lbs. These restrictions are designed to exclude commercial vehicles and heavy lorries. Passenger electric vehicles at 2-3 tonnes / 4,409-6,614 lbs don’t trigger restricted access even on limited-capacity bridges.

Tire and particulate concerns

Heavier vehicles accelerate tire wear. Electric vehicles require tires rated for higher loads and torque, which typically have reinforced sidewalls and harder rubber compounds.

Some research suggests heavier electric vehicles generate more tire particulate emissions (micro-plastics shed from tires) compared to lighter petrol equivalents. A 25% weight increase potentially creates 20-25% more tire wear particles.

But tire wear is predominantly influenced by driving style, not vehicle weight. Aggressive acceleration and hard braking create far more tire wear than gradual weight increases. The most significant factor in tire particulate generation is tire compound, with harder compounds shedding fewer particles despite supporting heavier loads.

From an infrastructure perspective, tire particulates don’t damage roads or bridges. They represent an environmental concern regarding air quality and waterway contamination, but don’t accelerate infrastructure deterioration.

Technical Specifications: Chassis, Platform, and Body-in-White Weights

Users searching for “typical EV chassis weight kg” or “body-in-white weight” want specific component-level data. These figures help understand where electric vehicle mass concentrates and how manufacturers optimize structural efficiency.

Body-in-white (BIW) specifications

Body-in-white refers to the vehicle’s structural shell after panels are welded but before paint, trim, or mechanical components are added. It’s the skeletal frame determining crash protection, rigidity, and overall structural integrity.

Petrol vehicle BIW (steel construction): 350-450 kg / 772-992 lbs for mid-size sedans, 400-550 kg / 882-1,213 lbs for SUVs.

Electric vehicle BIW (mixed materials): 280-380 kg / 617-838 lbs for mid-size sedans using aluminum-intensive construction, 350-480 kg / 772-1,058 lbs for SUVs.

The weight saving from aluminum BIW construction is approximately 20-25% compared to equivalent steel structures. High-strength steel (used in critical load-bearing areas) weighs similarly to standard steel but allows thinner sections, saving 5-10% overall.

Tesla Model 3 uses approximately 330 kg / 728 lbs of aluminum and mixed materials in its BIW. Comparable BMW 3 Series uses approximately 390 kg / 860 lbs of predominantly steel construction.

Chassis and platform weights

“Chassis” terminology differs between traditional automotive engineering and modern electric vehicle design. Traditional chassis refers to a separate frame (body-on-frame construction common in trucks). Platform refers to the underbody structure in unibody construction (most cars).

Electric vehicles increasingly use “skateboard” platforms where the battery pack forms structural components of the chassis itself. The battery housing acts as a stressed member, adding rigidity while integrating energy storage.

Traditional unibody platform (petrol vehicle): 280-380 kg / 617-838 lbs including front and rear subframes, floor pan, and structural reinforcements.

EV skateboard platform (including battery structure): 500-700 kg / 1,102-1,543 lbs including integrated battery housing, thermal management systems, and reinforced crash structures.

The additional 200-300 kg / 440-660 lbs in EV platforms isn’t wasted weight. It combines multiple functions: structural floor pan, battery containment, crash protection, and underbody aerodynamic smoothing. Separate equivalent systems in petrol vehicles would add 100-150 kg / 220-331 lbs, so the net penalty is 100-150 kg / 220-331 lbs rather than the full 300 kg / 660 lbs difference.

Battery pack mass specifications

Battery pack weight varies primarily by capacity (kWh) and secondarily by cell chemistry and packaging efficiency:

Small battery packs (40-50 kWh): 280-350 kg / 617-772 lbs

- Nissan Leaf 40 kWh: 303 kg / 668 lbs

- Typical energy density: 7.5 kg/kWh / 16.5 lbs/kWh

Medium battery packs (60-77 kWh): 400-520 kg / 882-1,146 lbs

- Tesla Model 3 Standard Range (60 kWh): ~410 kg / 904 lbs

- Tesla Model 3 Long Range (77 kWh): ~480 kg / 1,058 lbs

- Typical energy density: 6.5-6.8 kg/kWh / 14.3-15.0 lbs/kWh

Large battery packs (80-100 kWh): 540-680 kg / 1,190-1,499 lbs

- Tesla Model S (100 kWh): ~625 kg / 1,378 lbs

- Ford F-150 Lightning (131 kWh): ~820 kg / 1,808 lbs (larger pack for truck duty)

- Typical energy density: 6.2-6.8 kg/kWh / 13.7-15.0 lbs/kWh

These figures include battery cells, thermal management systems (cooling plates, pumps, fluids), protective casing, battery management electronics, and mounting structures. Pure cell weight is approximately 30-40% lower, with the difference representing necessary supporting systems.

Why these specifications matter for infrastructure

From a parking structure or road infrastructure perspective, these component weights are largely irrelevant. Engineers design for total vehicle gross weight, not individual component specifications.

But understanding component-level weights helps identify optimization opportunities. If battery energy density improves from 6.5 kg/kWh to 4.0 kg/kWh (achievable with next-generation solid-state batteries), a 75 kWh pack drops from 488 kg / 1,076 lbs to 300 kg / 661 lbs, saving 188 kg / 414 lbs.

That weight saving could reduce total EV weight to near-parity with petrol equivalents, eliminating infrastructure concerns entirely. Current trajectory suggests this technology arrives commercially in the 2030s.

Common Myths and Misunderstandings

Myth: Electric vehicles are 50% heavier than petrol cars, making them dangerous for aging infrastructure.

Reality: The typical weight increase is 20-30%, not 50%. A 1,600 kg / 3,527 lb petrol car becomes a 2,000 kg / 4,409 lb electric equivalent, not 2,400 kg / 5,291 lbs. Large electric trucks show bigger percentages but remain within commercial vehicle design categories that parking structures and roads already accommodate.

Myth: All the extra weight comes from batteries with no offsetting reductions.

Reality: Battery packs add 400-600 kg / 882-1,323 lbs but electric vehicles eliminate 100-150 kg / 220-331 lbs of petrol powertrain components (engine, gearbox, exhaust, fuel tank). Body-in-white weight reduces by 50-100 kg / 110-220 lbs through aluminum construction. Net additional weight is 250-450 kg / 551-992 lbs after offsets.

Myth: Parking garages were designed for 1990s cars weighing 1,200 kg, so 2,000 kg electric vehicles exceed capacity.

Reality: Engineering design standards don’t specify “average car weight = design load.” They specify distributed loads across floor slabs with safety factors of 1.5-2.0 times expected loading. Modern standards assume vehicle weights up to 2,500-3,000 kg / 5,512-6,614 lbs. Many 1990s structures were designed to accommodate delivery vans and commercial vehicles exceeding 3,000 kg / 6,614 lbs.

Myth: Electric vehicle weight concentrates on one point, creating excessive stress.

Reality: Vehicle weight distributes across four tire contact patches. Electric vehicles often achieve better weight distribution (50/50 front-rear) compared to front-heavy petrol cars (60/40 or worse). More balanced distribution reduces peak loading stress on parking structure slabs.

Myth: Roads and bridges can’t handle heavier electric vehicles.

Reality: Road design is dominated by heavy goods vehicle loads, not passenger cars. A single 40-tonne / 88,185 lb lorry causes more road damage than thousands of passenger cars. Bridge load ratings (typically 7.5-44 tonnes / 16,535-97,003 lbs) far exceed passenger vehicle weights. Adding 300-500 kg / 660-1,102 lbs to a 1,600 kg / 3,527 lb vehicle doesn’t approach infrastructure design limits.

Myth: If an electric vehicle fits in a parking space, the structure must be safe.

Reality: Height clearance and space dimensions don’t indicate load-bearing capacity. Older deteriorated structures may not safely support modern vehicle weights regardless of propulsion type. Structural assessments should evaluate load capacity, concrete condition, rebar corrosion, and maintenance history, not just whether vehicles physically fit.

Myth: The only solution is rebuilding all parking infrastructure.

Reality: Modern parking structures require no modifications. Older structures may need structural assessments to verify capacity, with targeted reinforcement where needed. Most require maintenance and repair (addressing concrete deterioration and water infiltration) rather than wholesale rebuilding.

What This Means for Electricians and Charging Infrastructure

The structural capacity debate obscures the genuine infrastructure challenge: electrical systems, not concrete slabs. Installing charging infrastructure in car parks, residential developments, and commercial properties creates the primary technical and logistical requirement for electric vehicle adoption.

Car park charging infrastructure requirements

A typical multi-storey car park with 200 parking spaces potentially requires 40-100 charging points to serve realistic electric vehicle adoption rates (20-50% of parked vehicles needing charging capability).

Each 7 kW home-style charger draws 32 amps at 230V. One hundred charging points create potential demand of 3,200 amps if all charge simultaneously. Actual demand is lower (load diversity factors apply) but electrical infrastructure must handle peak loading scenarios.

This requires: distribution board capacity upgrades, high-current cable installation throughout the structure, earthing and bonding systems for charging equipment, residual current protection for each charge point, and load management systems preventing simultaneous peak demand.

These electrical installations require qualified electricians who understand EV charging infrastructure specifications, not structural engineers assessing concrete capacity. The skills shortage in EV charging installation creates more immediate challenges than parking structure weight limits.

Residential and commercial installation growth

Home charging installation represents the largest segment of EV charging infrastructure. Most EV owners charge primarily at home using dedicated 7 kW or 22 kW charge points installed in garages or driveways.

Each home installation requires: electrical capacity assessment of the existing consumer unit, dedicated circuit installation from the main distribution board, RCD protection meeting BS 7671 requirements (UK) or NEC specifications (US), charge point mounting and commissioning, and final testing.

Workplace charging installations at commercial properties follow similar principles but at larger scale. A business car park with 20 allocated EV charging spaces requires coordinated installation of multiple charge points with load management systems preventing demand spikes when all employees arrive simultaneously at 9 AM.

Electricians qualified in EV charging infrastructure installation are positioned for sustained demand growth as electric vehicle adoption accelerates globally. The technical challenge isn’t whether vehicles are too heavy for parking structures, but whether electrical infrastructure can support charging demand.

Training pathways for electricians entering EV charging installation work typically require foundational qualifications (NVQ Level 3 in the UK, licensed electrician status in US/Canada/Australia) plus specialist EV charging courses covering charge point specifications, load calculations, and commissioning procedures. This creates accessible entry points for people considering a qualified electrician pathway focused on emerging electrical infrastructure demands.

"Electricians trained in EV charging infrastructure installation are positioning themselves for 10-20 years of consistent work as fleets electrify. Whether EVs weigh 1,800 kg or 2,300 kg doesn't change the fact that every EV needs charging infrastructure, and qualified electricians install it."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

The earning potential for electricians specializing in EV charging infrastructure reflects the technical expertise required and sustained demand. Across English-speaking countries, qualified EV charging installation specialists command premium rates: £300-450 per day in the UK, $400-600 per day in the US, similar rates in Canada and Australia. Understanding electrician earnings for specialists helps contextualize the career opportunity created by electric vehicle infrastructure demands.

The Actual Future: Weight Trends and Technology Development

Current electric vehicle weight represents a transitional phase in automotive electrification, not a permanent technical limitation. Multiple technology developments will reduce EV weights over the next decade.

Battery energy density improvements

Lithium-ion battery technology improves approximately 5-7% annually in energy density. Current batteries store approximately 250-270 Wh/kg (watt-hours per kilogram) / 113-122 Wh/lb at the pack level.

Next-generation lithium-ion improvements target 300-350 Wh/kg / 136-159 Wh/lb by 2030, reducing battery pack weight by 20-25% for equivalent capacity. A 75 kWh pack weighing 480 kg / 1,058 lbs today could weigh 360-385 kg / 794-849 lbs with improved chemistry, saving 95-120 kg / 209-265 lbs.

Solid-state batteries (still in development) promise 400-500 Wh/kg / 181-227 Wh/lb, potentially halving battery pack weight compared to current technology. Commercial availability is projected for 2030-2035 for premium vehicles, mass market adoption by 2035-2040.

If solid-state technology delivers promised improvements, a 75 kWh pack could weigh 150-187 kg / 331-412 lbs, saving 290-330 kg / 639-728 lbs compared to current lithium-ion packs. That single component improvement eliminates most of the electric vehicle weight penalty.

Structural and materials optimization

Current electric vehicles represent first-and second-generation designs. Many were adapted from existing petrol vehicle platforms, inheriting structural compromises from non-optimized architecture.

Purpose-designed electric vehicle platforms (like Tesla’s current generation, Volkswagen MEB, General Motors Ultium, Hyundai E-GMP) optimize structure around battery integration, reducing redundant components and unnecessary reinforcement.

Third-generation platforms currently in development emphasize weight reduction through: advanced high-strength steels (requiring less material for equivalent strength), carbon fiber composites in non-structural panels, aluminum castings replacing multiple welded components (reducing weight and cost simultaneously), and integrated structural battery designs where battery casing forms part of vehicle structure.

Industry targets suggest 15-20% total vehicle weight reduction is achievable through design optimization alone without battery improvements. Combined with battery density improvements, this creates pathway to electric vehicles matching or undercutting current petrol vehicle weights by 2035.

Market pressure and regulatory incentives

Vehicle weight directly impacts energy consumption. Heavier vehicles require larger batteries to achieve acceptable range, which adds more weight, requiring even larger batteries in a compounding cycle.

Manufacturers face regulatory pressure to improve efficiency. Reducing vehicle weight by 100 kg / 220 lbs improves range by approximately 5-8% without increasing battery capacity. This creates strong economic incentive to minimize weight.

Consumer preferences also favor lighter vehicles for handling, performance, and tire wear characteristics. Electric vehicle buyers increasingly scrutinize efficiency metrics, creating market pressure reinforcing regulatory incentives.

Infrastructure implications of lighter future EVs

If electric vehicles achieve weight parity with petrol equivalents by 2035-2040, current infrastructure concerns become historical artifacts of transitional technology phase.

Parking structures built today with 3.0 kN/m² design loads will have surplus capacity when 2,000 kg / 4,409 lb electric vehicles replace current 1,600 kg / 3,527 lb petrol cars with similar-weight 1,700-1,800 kg / 3,748-3,968 lb next-generation electric equivalents.

The primary infrastructure challenge will remain electrical capacity, not structural capacity. Even if vehicles weigh identically to petrol equivalents, they still require charging infrastructure which petrol vehicles don’t. The electrician skills shortage for EV charging installation will persist regardless of vehicle weight trajectory.

Electric vehicles are heavier than petrol equivalents by approximately 20-30%, adding 200-500 kg / 440-1,102 lbs depending on vehicle size and battery capacity. This represents factual engineering reality, not speculation.

Modern parking structures in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, and other English-speaking countries are designed with sufficient capacity for vehicles up to 3,000 kg / 6,614 lbs. The vast majority of electric vehicles fall well below this threshold. Even heavy electric trucks and SUVs at 2,700-3,200 kg / 5,953-7,055 lbs remain within design parameters that already accommodate petrol SUVs and commercial vehicles.

Older parking structures built before modern design standards may require structural assessments to verify load capacity, but failures attributed specifically to electric vehicle weights number zero in documented engineering investigations. Failures occur due to aging infrastructure, deferred maintenance, concrete deterioration, and rebar corrosion regardless of vehicle propulsion type.

Road and bridge infrastructure handles electric vehicle weights without modification. Highway engineering design is dominated by heavy goods vehicle loads that dwarf passenger car weights. Adding 300 kg / 660 lbs to a passenger car doesn’t approach the structural impact of a 40-tonne / 88,185 lb articulated lorry.

The genuine infrastructure challenge is electrical capacity, not structural capacity. Installing charging infrastructure at scale requires qualified electricians with specialist training in EV charge point installation, load management systems, and distribution board capacity planning.

This creates sustained employment demand across English-speaking countries as electric vehicle adoption accelerates. The technical debate about vehicle weight obscures the practical reality that every electric vehicle requires charging infrastructure regardless of how much it weighs, and qualified electricians install that infrastructure.

From an infrastructure planning perspective, focus should shift from questioning whether parking structures can support electric vehicles (they can) to ensuring adequate electrical infrastructure exists to charge them (it often doesn’t). That’s the genuine policy and technical challenge requiring attention and investment through the 2030s.

FAQs

Why are electric vehicles typically 20–30% heavier than petrol or diesel cars?

Electric vehicles are heavier mainly because of their lithium-ion battery packs, which typically weigh between 300 and 600 kilograms in mid-sized cars. These batteries are required to deliver practical driving range and performance. Petrol and diesel vehicles store energy in much lighter fuel tanks, with fuel mass forming only a small proportion of overall vehicle weight during use. Engineering comparisons across the UK, North America, and Australia consistently show a 20–30 percent kerb-weight increase for like-for-like vehicle classes. While the added mass lowers the centre of gravity and improves stability, it remains a clear engineering trade-off driven by current battery energy density.

Which components add the most weight in an EV, and what components are removed compared to an ICE vehicle?

The battery pack is the largest single contributor to EV weight, often accounting for 25–40 percent of total kerb weight. Smaller additions include power electronics, electric motors, high-voltage cabling, and battery cooling systems. In return, EVs remove the internal combustion engine block, which can weigh 150–250 kilograms, multi-speed gearboxes (around 50 kilograms), and exhaust systems, fuel tanks, and catalytic converters, saving up to 100 kilograms. Despite these removals, the net weight increase remains due to the energy storage requirement, though the mass is evenly distributed across the chassis.

Does the weight difference vary by vehicle type, and if so, why?

Yes. Smaller city EVs typically show a 15–20 percent increase because they use smaller battery packs for shorter ranges. Mid-size saloons and SUVs usually fall within the 20–30 percent range, balancing range, comfort, and performance. Larger vehicles, including electric pick-ups and vans, can exceed 40 percent due to significantly larger batteries needed for towing or long-distance use. The variation is driven primarily by battery size rather than inconsistent engineering standards.

Is the claim that EVs are “30% heavier” always accurate?

No. The 30 percent figure is a useful average for mid-sized passenger vehicles but not a universal rule. Compact EVs may only be 10–15 percent heavier, while performance-focused models often sit around 20–25 percent. Conversely, large luxury or off-road EVs can exceed 35 percent. These differences reflect design choices, range targets, and material use rather than measurement inconsistencies. The figure should be understood as indicative, not absolute.

Are electric vehicles too heavy for multi-storey car parks?

No. Modern multi-storey car parks in the UK are designed with conservative load allowances that comfortably accommodate EV weights. Typical EV kerb weights of 1,800–2,200 kilograms fall well within design loadings, which include significant safety margins. Axle loads are also evenly distributed and remain below critical thresholds for reinforced concrete slabs. Older car parks may occasionally require assessment, but widespread structural risk has not been identified. The main EV-related consideration in car parks is ventilation, not weight.

What is the difference between total vehicle weight and axle load, and why does it matter?

Total vehicle weight refers to the full mass of the vehicle, including occupants and cargo. Axle load describes how that weight is distributed across the front and rear axles. Infrastructure wear and structural stress are driven more by axle load than total mass. EVs generally distribute weight evenly due to floor-mounted batteries, keeping axle loads comparable to conventional vehicles. This balanced distribution reduces localised stress on roads and structures.

Do heavier EVs significantly increase road wear compared to petrol or diesel cars?

Heavier EVs do increase road wear slightly, but not to a level considered critical by transport authorities. While engineering models show that higher axle loads increase pavement damage, real-world fleet impacts remain modest. Studies in the UK and comparable countries indicate increases of under 5 percent in annual wear, which is already accounted for in resurfacing schedules. EVs also tend to replace heavier diesel vans in urban driving, offsetting some of the impact.

Are bridges and older infrastructure at greater risk due to EV weight?

No. Bridges are designed with load factors well above normal vehicle use, including safety margins of 1.5–2.0. EV weights remain comfortably within these limits. Older bridges may have existing restrictions, but EVs do not introduce new risk beyond what current assessments already manage. Regular inspections and monitoring continue to govern structural safety, with EV weight treated as a known, manageable variable.

Does extra EV weight affect everyday parking safety?

In practical terms, no. Parking structures are designed for worst-case loading scenarios and can easily accommodate EV axle and bay loads. Distributed tyre contact and conservative engineering limits prevent excessive deflection or structural stress. Real-world use across the UK, North America, and Australia has not shown parking-related safety issues caused by EV weight.

If vehicle weight is not the main issue, what infrastructure challenge matters more for EVs?

Electrical capacity and charging infrastructure present the greater challenge. Widespread EV adoption increases peak demand on local grids, particularly with rapid chargers drawing 50–350 kilowatts. Grid reinforcement, transformer upgrades, and smart charging systems are required to manage this demand safely. Compared with these dynamic electrical constraints, vehicle weight is a secondary and largely accommodated issue in infrastructure planning.

References

- Institution of Structural Engineers – Design recommendations for multi-storey and underground car parks – https://www.istructe.org/resources/guidance/design-recommendations-for-multi-storey-car-parks/

- ASCE 7 – Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures – https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/codes-and-standards/asce-7

- UK Steel Construction – Car Parks Design Standards – https://steelconstruction.info/Car_parks

- Building Engineer – Safety concerns over multi-storey car parks – https://www.buildingengineer.org.uk/news/safety-concerns-over-significant-increase-overloaded-multi-storey-car-parks

- Structure Magazine – Electrical Vehicles and Parking Structures – https://www.structuremag.org/article/electrical-vehicles-and-parking-structures

- Kelley Blue Book – Heaviest Electric Vehicles Data – https://www.kbb.com/car-advice/heaviest-electric-vehicles

- Freep – Why EVs Are Heavier Than ICE Vehicles – https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/2025/08/18/why-are-evs-heavier-than-ice-vehicles/85616877007

- ScienceDirect – Electric Vehicle Weight Impact Research – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304389421015910

- University of Tennessee Center for Transportation Research – EVs Heavier Than Cars Study – https://ctr.utk.edu/evs-heavier-than-cars-are-they-harder-on-roads

- Nulo Innovations – BIW for Electric Vehicles – https://www.nuloinnovations.com/articles/biwforelectricvehicle

- Just Auto – Battery Pack Integration Into Body-in-White – https://www.just-auto.com/sponsored/the-integration-of-battery-packs-into-the-body-in-white

- Center for Auto Safety – Enormous Electric Vehicles Report – https://www.autosafety.org/enormous-electric-vehicles

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 11 February 2026. This page is maintained; we correct errors and refresh sources as vehicle specifications, building standards, and infrastructure regulations change. Vehicle weight specifications based on manufacturer data current as of publication date. Building and infrastructure standards reflect current UK (Eurocodes), US (ASCE 7/IBC), Canadian (NBC), and Australian (BCA) requirements. Battery technology projections represent industry consensus estimates and may change as technology develops. Next review scheduled following any major updates to parking structure design standards or documented structural incidents attributed to vehicle weights (anticipated annual review cycle).