Career Development and Vocational Education Pathways in a Changing Technical Workforce

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Complete rewrite examining evolution from linear to non-linear vocational education model, focusing on structural shifts in technical workforce development and lifelong learning requirements

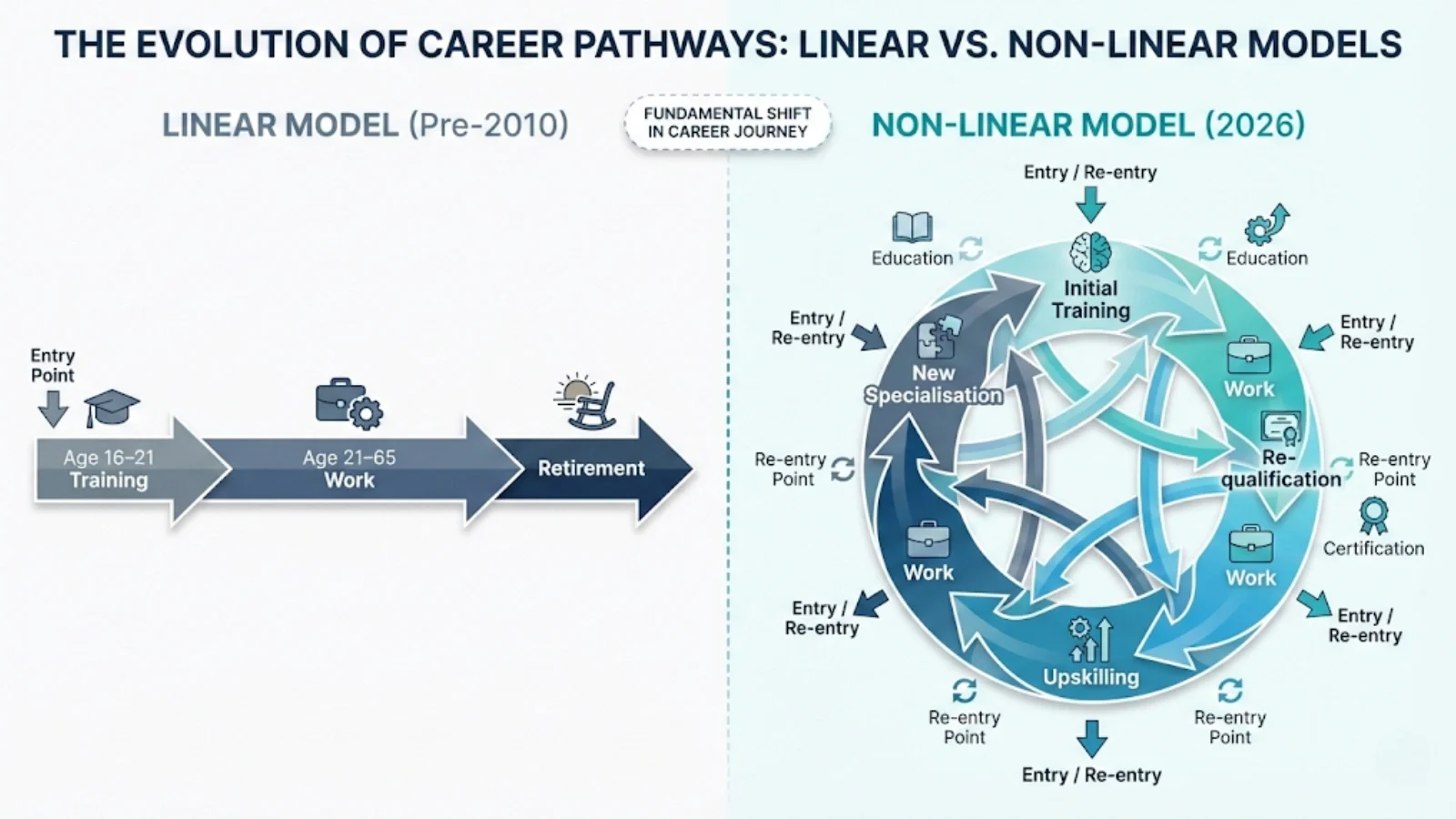

The UK vocational education system was built on an assumption that no longer holds: that you train once between ages 16 and 21, then work in that trade for 40 years using the same knowledge. This front-loaded, linear model defined technical workforce development from the 1960s through the early 2000s.

That system is collapsing. Not from failure, but from obsolescence.

Today’s technical workforce operates on a fundamentally different model: continuous, iterative training throughout working life. Electricians who qualified in 2010 with NVQ Level 3 and 17th Edition Wiring Regulations now need 18th Edition updates, EV charging qualifications, solar PV installation credentials, and inspection/testing certifications that didn’t exist when they trained. These aren’t optional professional development, they’re mandatory requirements to remain employable.

The shift from “train once, work forever” to “lifelong churning” of qualifications creates challenges the vocational system wasn’t designed to handle. Adult learners at 35 or 45 can’t access apprenticeships structured for 16-year-olds. Qualification stacking outpaces curriculum development. Assessment capacity bottlenecks prevent people with theory knowledge from gaining practical certification. Skills shortages persist despite rising training participation.

This article examines how vocational education pathways evolved in the UK, what structural changes forced the shift from linear to non-linear career development, what the current vocational landscape looks like in 2026, why career progression now requires continuous re-entry into training rather than single qualification events, and how technical trades like electrical work exemplify these system-wide challenges.

If you’re considering career change into technical work, already working but facing new qualification requirements, or trying to understand why skills shortages persist despite training availability, this explains the system-level forces shaping vocational education and workforce development.

Historical Vocational Pathways: The "Once and Done" Model

Understanding current challenges requires examining what the vocational system was originally designed to achieve and for whom.

The School-to-Work Pipeline (1960s-2000s)

Post-war vocational education operated through a clear pipeline: 16-year-olds left school, entered apprenticeships or Further Education colleges, gained trade qualifications by age 21, then worked in that trade until retirement. The system assumed stable employment, single-employer careers, and minimal technological disruption requiring retraining.

Industry Training Boards, formalized in the 1960s, coordinated craft and technician training for manufacturing and construction sectors. Modern Apprenticeships, introduced in 1993, extended this model with NVQ Level 2 (Foundation) and Level 3 (Advanced) frameworks targeting youth aged 16-24.

Participation peaked in the 1960s-1970s with approximately 110,000 apprentices from 750,000 school leavers annually. The emphasis was supply-side: train sufficient numbers to meet industry demand, with FE colleges delivering theory and employers providing workplace experience.

Who the System Served

The historical model worked well for:

- Young men entering traditional trades (electrical, plumbing, mechanical) directly from school

- Those in manufacturing sectors with structured training programmes

- Workers in stable employment with single employers willing to invest in long-term training

Who It Excluded

The system systematically underserved:

- Women in male-dominated technical trades

- Adults seeking career changes after age 25

- Ethnic minorities facing recruitment barriers in traditional apprenticeship sectors

- Anyone needing flexible or modular training around existing work or family commitments

- Those in non-traditional employment (self-employed, multiple short-term employers)

Stability Assumptions

The system assumed:

- Technology would change gradually, allowing decades of use from initial qualifications

- Regulatory requirements would remain largely static

- Single-employer loyalty would fund and structure training

- Manual skills would remain valued over theoretical or digital competence

These assumptions held through the 1980s and 1990s but began breaking down in the 2000s as manufacturing declined, self-employment increased, and technology acceleration disrupted stable trade practices.

What Changed: Structural Shifts in the Technical Workforce

Multiple converging forces dismantled the linear career model between 2010 and 2026.

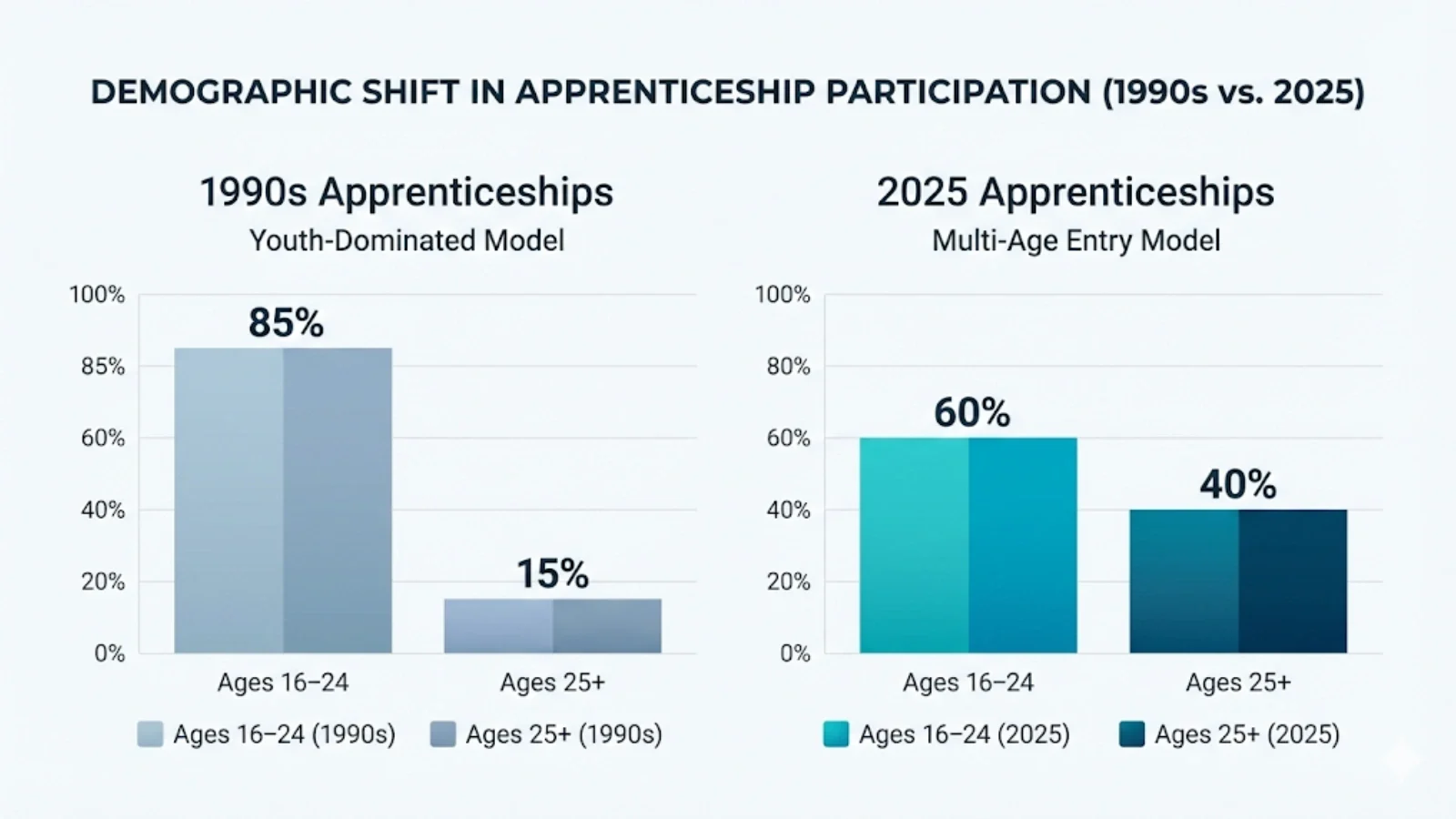

The Rise of Adult Learners

DfE apprenticeship data shows dramatic demographic shifts: in 2025, approximately 40% of apprenticeship starts were by adults aged 25 and over, compared to minimal adult participation in the 1990s. This reflects:

- Economic necessity: Manufacturing decline and retail sector instability forced mid-career transitions into technical trades offering better employment security

- Delayed entry: Many adults completed academic routes (A-Levels, degrees) before recognizing vocational paths offered superior earnings and job satisfaction

- Career pivots: White-collar workers facing automation or sector decline sought manual trades with tangible outputs and direct client relationships

These adult learners brought workplace maturity but lacked formal qualifications, creating mismatches with systems designed for school leavers with theoretical knowledge but no employment experience.

Technological Velocity

The pace of technological change in technical trades accelerated beyond curriculum development cycles:

- Green Industrial Revolution: EV charging infrastructure, solar PV installations, heat pump electrical work, and battery storage systems created entirely new specializations requiring additional qualifications beyond baseline electrical training

- Digital integration: Smart home systems, building management platforms, and IoT-connected electrical installations demand IT competence alongside traditional wiring skills

- Automation and AI: Diagnostic tools, automated testing equipment, and digital documentation systems changed daily work practices requiring continuous upskilling

In electrical work specifically, BS 7671 Wiring Regulations updates (17th Edition 2008, 18th Edition 2018, Amendment 4 2026) meant electricians trained in 2010 needed requalification multiple times to remain current. This created the “qualification treadmill” where initial training became perpetually insufficient.

Self-Employment Growth

The shift from employed electricians to self-employed contractors fundamentally changed training economics:

- Cost burden shift: Employers historically funded apprenticeship training. Self-employed electricians now self-fund ongoing qualifications, creating financial barriers to compliance

- Time pressure: Employed electricians could attend courses during paid work time. Self-employed workers lose income during training, discouraging participation

- Modular demand: Self-employed workers need specific qualifications for immediate client needs rather than comprehensive training programmes, driving demand for short courses

CITB data shows construction sector self-employment increased significantly, particularly among electricians, heating engineers, and other technical trades where sole trader models became dominant.

Regulatory Acceleration

Technical trades faced increasing regulatory complexity requiring continuous requalification:

- Building Regulations Part P: Notifiable work requirements and Competent Person Scheme standards evolved

- EAS 2024 deadlines: New qualification requirements for inspection/testing and low-carbon work by October 2026

- Insurance requirements: Public liability and professional indemnity insurers demanded evidence of current qualifications, not just historical credentials

- Consumer protection: Homeowner awareness of proper qualifications increased, making outdated credentials a commercial liability

Understanding the electrician career path now requires appreciating that qualification is continuous rather than a one-time achievement at career start.

The Current Vocational Education Landscape (2026)

The 2026 vocational system is a hybrid of state-funded initiatives and private market provision attempting to serve both traditional youth pathways and emerging adult retraining needs.

Apprenticeships: Standards vs Frameworks

Modern apprenticeships operate through “Standards” (occupational profiles with end-point assessments) rather than older unit-based “Frameworks.” Funded through the Apprenticeship Levy (£3+ billion annually), they remain the gold standard for structured vocational training.

Current realities:

- Duration typically 2-4 years depending on level and sector

- Minimum wage requirements create barriers for adult learners with financial responsibilities

- Employer preference for younger hires limits adult access despite policy encouragement

- End-point assessment backlogs create delays between training completion and qualification achievement

Who they serve well: Young people transitioning from school or college with minimal financial commitments, able to accept apprentice wages (£6.40/hour minimum for under-18s or first year).

Who they struggle to serve: Adults aged 30+ needing career change but unable to accept minimum wage, those requiring flexible part-time arrangements, self-employed workers needing specific qualifications without full apprenticeship commitment.

Skills Bootcamps: Just-in-Time Learning

Introduced as flexible 12-16 week intensive courses at Levels 3-5, free for adults aged 19+, with government funding covering costs and often including job interview guarantees with participating employers.

Benefits:

- Speed of qualification compared to 2-4 year apprenticeships

- Focus on specific employer needs rather than generic curricula

- Accessible to adults with work/family commitments

- No opportunity cost of leaving existing employment

Limitations:

- Lack of depth compared to traditional apprenticeships

- Limited practical experience component

- No employer obligation to hire participants post-completion

- Questions about long-term employability outcomes vs apprenticeship route

Approximately 40,000+ learners participated in Skills Bootcamps during 2025-26, representing rapid growth but still small proportion of overall vocational training.

Further Education Colleges vs Private Providers

FE colleges remain hubs for regional 16-19 provision, delivering approximately 60% of vocational training. However, adult technical training increasingly occurs through private providers offering modular, accelerated courses.

FE college model:

- Comprehensive programmes aligned with national standards

- Access to workshop facilities and equipment

- Lower costs (often fully funded for eligible learners)

- Structured progression pathways

Private provider model:

- Speed and flexibility (weekend courses, evening classes)

- Specialist focus (e.g., electrical-only training centres)

- Higher costs (often £2,000-8,000 for Level 3 qualifications)

- Variable quality and limited oversight

The split between FE and private provision creates a two-tier system where those with money access fast-track routes while those dependent on public funding face longer timelines and capacity constraints.

Adult Skills Fund and Free Courses for Jobs

Government funding (£2.5+ billion annually through Adult Skills Fund) supports employment-focused adult learning in non-devolved areas of England. “Free Courses for Jobs” initiative provides full funding for first Level 3 qualifications for adults without existing qualifications at that level.

Impact:

- Removes cost barriers for eligible learners

- Focuses on qualifications with clear employment outcomes

- Prioritizes sectors with identified skills shortages

Gaps:

- Doesn’t cover living costs during training

- Limited to first Level 3 (doesn’t help those with existing qualifications needing updates)

- Regional capacity constraints in FE delivery

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training with 20+ years experience, explains the support structure challenge:

"Adult learners bring workplace experience but often lack formal qualifications, while young apprentices have fresh theoretical knowledge but no site maturity. Both need different support structures. The vocational system historically focused on the 16-year-old school leaver pathway, which doesn't serve either group well when they're entering at 25, 35, or 45."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

Career Development as Non-Linear Process

The career ladder has been replaced by a lattice. Technical workers now enter, exit, and re-enter training multiple times throughout working lives rather than following single linear progression from qualification to retirement.

Staged Entry: Self-Funding Before Employment

Unlike the historical apprenticeship model where employers recruited unqualified school leavers and funded their training, many adults now self-fund entry-level qualifications (Level 2/3) before seeking employment.

Typical pattern:

- Self-fund Level 2 qualification while employed elsewhere (evenings/weekends)

- Seek electrical trainee position with partial qualifications

- Complete Level 3 through employer support or continued self-funding

- Gain employment as qualified electrician

- Build NVQ portfolio through workplace evidence

- Complete AM2 assessment for full certification

This staged approach spreads costs and reduces employment barriers but extends qualification timeline from 2-3 years to 4-5 years, delaying full earning potential.

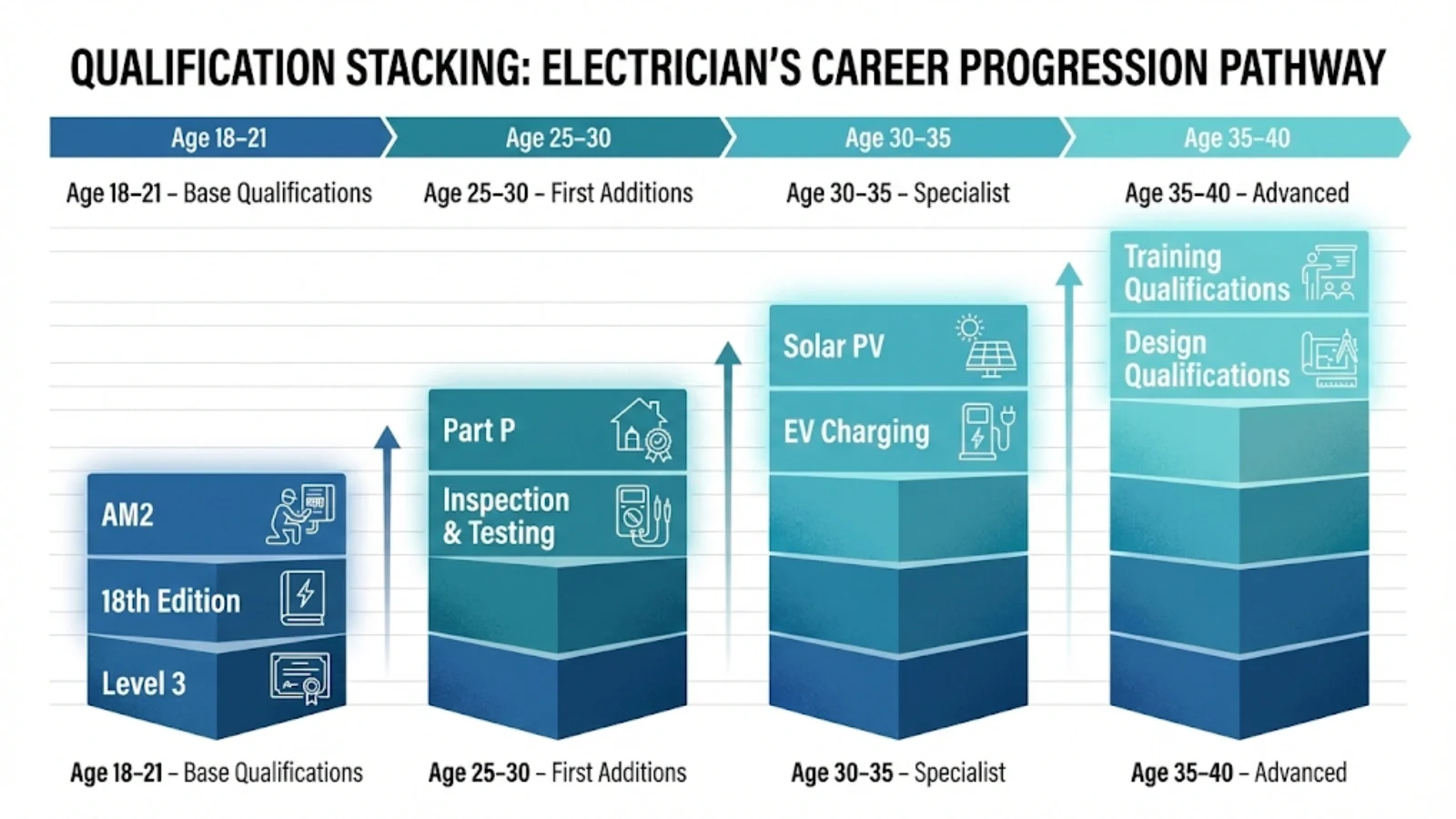

Qualification Stacking: Continuous Professional Development Becomes Mandatory

Technical workers now accumulate qualifications throughout careers rather than completing training once.

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager at Elec Training, describes the reality:

"We see electricians returning for additional qualifications throughout their careers. 18th Edition updates every few years, inspection and testing qualifications for EICR work, EV charging installation, solar PV - these stack onto base qualifications rather than replace them. It's ongoing professional development becoming mandatory rather than optional."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

Common stacking patterns in electrical work:

- Base qualifications: Level 3, 18th Edition, AM2 (initial career entry)

- First additions (2-5 years): Inspection and testing for EICR requirements in the UK, Part P Competent Person Scheme membership

- Specialist additions (5-10 years): EV charging installation, solar PV, heat pump electrical work

- Advanced additions (10+ years): Design and verification, advanced inspection, training/assessment qualifications

Each addition costs £500-3,000 and requires 2-16 weeks depending on complexity. Over a 40-year career, an electrician might spend £15,000-30,000 and 12-18 months in various training courses beyond initial qualification.

Multiple Re-Entry Points

Modern vocational pathways include numerous re-entry points rather than single initial entry:

Entry Point 1: School leaver (16-18) → Traditional apprenticeship or FE college Level 2/3

Entry Point 2: Young adult (19-24) → Skills Bootcamp or adult apprenticeship after trying academic route

Entry Point 3: Career changer (25-40) → Self-funded Level 2/3 followed by employment seeking, or direct entry if transferable skills

Entry Point 4: Mid-career specialist (40+) → Adding new specializations (EV, solar, etc.) to existing electrical qualification

Entry Point 5: Experienced re-credentialing → Updates to regulations (18th Edition), scheme requirements, or insurance mandates forcing requalification

This multiplicity creates flexibility but also confusion about “correct” pathways and makes career planning more complex than historical linear model.

Experience-Led Progression: Recognition of Prior Learning

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) theoretically allows adults to bypass redundant training by demonstrating existing competence. In practice, RPL application remains inconsistent across sectors and providers.

Where it works: Adults with significant electrical experience gained informally (working with qualified electricians, military electrical roles, overseas qualifications) can sometimes fast-track through Level 2 theory to focus on Level 3 and NVQ portfolio.

Where it struggles: RPL assessment capacity is limited, evidence requirements are strict, and many providers default to full course delivery rather than individual assessment due to administrative burden.

The gap between RPL theory and practice forces many experienced adults to repeat training they don’t need, wasting time and resources while capacity shortages prevent others from accessing training at all.

Technical Trades as Case Study: The Qualification vs Competence Gap

Electrical work exemplifies vocational education challenges because it operates as a “license to practice” environment where regulatory requirements create mandatory training demand not seen in less regulated sectors.

The Three-Level Competence Model

Electrical competence requires three distinct achievements, each with separate assessment:

Level 1: Knowledge (Classroom Theory)

- BS 7671 Wiring Regulations understanding

- Health and safety principles

- Electrical theory and calculations

- Delivered through FE colleges or private providers

- Assessed through written/multiple-choice exams

Level 2: Performance (Workplace Evidence)

- NVQ Level 3 portfolio demonstrating installations completed

- Evidence of safe isolation, testing, and certification

- Requires employment with qualified supervision

- Assessed through portfolio review by NVQ assessors

Level 3: Competence Validation (Practical Assessment)

- AM2 practical examination under timed, observed conditions

- Demonstrates ability to complete installation meeting BS 7671 standards

- Requires physical attendance at testing centres

- Assessed by qualified AM2 examiners

The Gap Between Levels

Someone can complete Level 1 (theory) in 12-16 weeks through intensive course. But without Level 2 (employment for NVQ portfolio) and Level 3 (AM2 assessment slot), they cannot work as qualified electrician regardless of theoretical knowledge.

This creates the bottleneck where training providers can deliver theory quickly, but assessment capacity (NVQ assessors, AM2 testing centres) limits throughput. During 2020-2022, COVID-related closures created 12-18 month backlogs in AM2 assessment, meaning people who completed theory in 2020 couldn’t finish qualification until 2022.

Why Regulation Drives Continuous Training

Unlike general management or office work where experience can substitute for formal qualifications, technical trades have hard regulatory boundaries:

- Building Regulations Part P: Notifiable domestic work requires self-certification through Competent Person Schemes or building control notification

- Insurance requirements: Public liability insurers require evidence of current qualifications for coverage validity

- Client expectations: Homeowners increasingly verify electrician credentials before hiring

- Scheme membership: NICEIC, NAPIT, and other schemes require ongoing qualification currency for membership maintenance

These regulatory requirements mean outdated qualifications aren’t just disadvantageous, they’re disqualifying. An electrician with 2010 qualifications but no 18th Edition update cannot legally self-certify work or maintain scheme membership, effectively ending their employability in domestic electrical work.

Skills Shortages Despite Training Availability

A persistent puzzle: why do skills shortages exist when training participation increases?

The electrical sector needs approximately 12,000 new qualified electricians annually to meet net-zero targets and replace retirees. Apprenticeship starts remain flat at 7,500-7,600 annually, creating a 4,500-person annual deficit.

But training course enrollments are higher than these figures suggest. The gap comes from:

- Completion rates: Not everyone who starts training finishes. Financial pressures, employment difficulties, or assessment failures prevent completion.

- Assessment bottlenecks: More people complete theory than can access AM2 assessment slots, creating qualified-in-theory but not qualified-in-practice populations.

- Experience requirements: People hold qualifications but lack the 2-3 years post-qualification experience employers demand for independent work.

- Regional mismatches: Training concentrates in urban areas while work opportunities exist in regions with limited training provision.

The “qualification vs competence” gap means headline training numbers don’t translate directly into workforce capacity increases, perpetuating shortages despite apparent training availability.

Financial Barriers to Continuous Qualification

The shift from employer-funded initial training to worker-funded ongoing qualification creates economic barriers:

Average average electrician pay in the UK is approximately £30,000-35,000 annually for qualified workers. Updating qualifications every 5-7 years at £500-3,000 per update represents 1-10% of annual income, excluding lost earnings during training time.

Self-employed electricians particularly struggle because training time means no invoice, no income. A two-week course costs not just the £1,500 course fee but also £1,200-1,500 in lost earnings, doubling the real cost.

These financial pressures delay or prevent qualification updates, contributing to workforce with technically outdated credentials despite formal qualification holdings.

Common Misconceptions About Vocational Pathways

Several persistent myths about vocational education create unrealistic expectations and poor decision-making.

Myth: “Vocational routes are only for school leavers”

Reality: DfE data shows 40% of apprenticeship starts in 2025 were by adults aged 25 and over. Mid-career entry into technical trades is now common, driven by economic transitions, career dissatisfaction, and recognition that academic routes don’t guarantee employment security.

Adult participation increased across all vocational pathways (apprenticeships, Skills Bootcamps, FE college courses), reflecting that vocational education now serves lifelong learning needs rather than just initial career entry.

Myth: “Once qualified, you’re set for life”

Reality: Qualification stacking is now mandatory in regulated technical trades. BS 7671 updates, new technology qualifications (EV, solar, smart systems), and regulatory requirement changes mean initial qualifications become insufficient within 5-7 years.

Career development requires continuous training investment throughout working life, not single front-loaded qualification event.

Myth: “Short courses make you fully qualified”

Reality: Intensive courses provide theoretical knowledge but cannot replace workplace competence development and assessment requirements. A 12-week Skills Bootcamp teaches electrical theory, but NVQ portfolios require documented site work over extended periods, and AM2 assessment requires practical demonstration that needs preparation beyond classroom learning.

Marketing claims about “fast-track” qualifications often omit the employment, portfolio building, and assessment stages that extend actual qualification timelines to 2-3 years minimum regardless of theory course duration.

Myth: “Academic routes are always safer career choices”

Reality: Graduate underemployment and degree-level job automation challenge assumptions about academic superiority. Technical trades with hard regulatory requirements (electrical, plumbing, gas engineering) demonstrate stronger employment prospects and earnings comparable to or exceeding graduate averages.

Career security increasingly comes from competence in non-automatable manual skills rather than theoretical knowledge that AI and automation can replicate.

Myth: “Training availability solves skills shortages”

Reality: Local Skills Improvement Plans and industry reports show that training availability doesn’t guarantee workforce capacity increases. Assessment bottlenecks, experience requirements, financial barriers, and regional mismatches mean people can access training but not complete qualification or find employment.

Skills shortages persist not from lack of training places but from systemic bottlenecks in qualification completion and workforce integration.

System Limitations and Structural Challenges

The current vocational education landscape faces several constraints that training expansion alone cannot resolve.

Assessment Capacity Constraints

Physical assessment infrastructure limits throughput regardless of training demand:

- AM2 testing centres: Limited number of facilities with calibrated equipment and qualified assessors

- NVQ assessors: Shortage of qualified assessors for portfolio review and workplace observation

- Workshop facilities: FE colleges facing capacity constraints for practical training with multiple cohorts

During regulatory deadline periods (like October 2026 EAS requirements), these bottlenecks intensify as existing workers seek updates simultaneously with new entrants seeking initial qualifications.

FE Funding and Regional Capacity

Further Education colleges face funding pressures limiting course offerings:

- Real-terms funding decreases over past decade

- Building maintenance backlogs affecting workshop quality

- Staff recruitment challenges in technical teaching roles

- Regional variations in provision creating geographical barriers

These constraints mean publicly-funded pathways have longer waiting lists and limited flexibility compared to private providers, creating two-tier access based on financial means.

The Experience Paradox

Entry-level positions require experience, but gaining experience requires employment:

- Employers want electricians with NVQ portfolios, but portfolios require employment

- Insurance costs make employing unqualified trainees expensive for small contractors

- Self-employment route unavailable without complete qualifications and scheme membership

- Adult learners with financial commitments can’t accept unpaid or minimum wage trainee positions

This creates a “catch-22” where career change into technical trades requires resources (savings to live on during low-wage training period, time for portfolio building, access to supportive employers) that exclude many potential entrants.

Variable Employer Engagement

Skills shortage solutions depend on employer participation in training, but engagement remains inconsistent:

- CITB data shows employer-provided training fell from 67% of construction employers (2018) to 42% (2021)

- Apprenticeship Levy creates incentives for larger employers but doesn’t address SME training provision

- Self-employment growth means more workers lack employer support for ongoing qualification

Without employer engagement providing workplace learning environments, classroom theory alone cannot create workforce-ready electricians regardless of training course quality.

The UK vocational education system is caught between models: the historical linear pathway designed for youth no longer functions, but the emerging lifelong learning system isn’t fully developed.

What’s clear:

Career development in technical trades now requires continuous qualification throughout working life. The “train once, work forever” model is obsolete. Initial qualifications are necessary but insufficient, requiring ongoing additions for technology changes, regulatory updates, and specialization development.

Adult entry into vocational pathways increased significantly, but system design still prioritizes 16-year-old pathways. Financial structures, timeline expectations, and support mechanisms don’t adequately serve those entering at 25, 35, or 45 with different circumstances and needs.

Skills shortages persist not from training unavailability but from systemic bottlenecks in assessment capacity, experience requirements, and qualification-to-competence gaps. More training places alone won’t resolve workforce shortages without addressing these structural constraints.

What’s evolving:

Skills Bootcamps and modular qualifications represent system adaptation toward flexibility and speed, though questions remain about depth and long-term employability outcomes compared to traditional apprenticeships.

Qualification stacking and non-linear progression are becoming normalized rather than exceptional, reflecting acceptance that career development is continuous rather than front-loaded.

Policy focus on employer-led skills planning through Local Skills Improvement Plans and Skills England attempts to align training provision with regional needs, though effectiveness remains to be proven.

What remains unresolved:

How to fund lifelong learning when employers won’t pay for ongoing worker qualification, workers can’t afford self-funding, and public funding focuses on initial rather than continuous training.

How to balance speed (Skills Bootcamps) versus depth (apprenticeships) when both serve legitimate needs but create different workforce outcomes.

How to serve both youth pathways and adult retraining through single vocational system designed originally for only one cohort.

The vocational education system is transitioning from linear to iterative, from youth-focused to age-inclusive, from single qualification to continuous learning. That transition is incomplete, creating current tensions between what the system was designed to do and what it’s now asked to achieve.

FAQs

The UK vocational system originated from medieval craft guilds, where apprenticeships lasted 5–9 years, binding young people to a master craftsman for life-long skill acquisition in a single trade. This model persisted through the Industrial Revolution, as guilds were abolished but the assumption of stable, linear careers remained, influenced by societal structures emphasising tradition and occupational identity. By the mid-20th century, systems like the 1964 Industrial Training Act reinforced one-time training, with around one-third of young male school leavers entering apprenticeships in the 1960s. Evidence from historical analyses shows this was based on predictable job markets, where technological change was slow, and workers stayed in roles for decades. Post-1980s reforms introduced more flexibility, but the core assumption lingered until recent decades due to economic shifts.

What this means in practice

- Training focused on depth in one occupation, with limited pathways for switching trades.

- Systems prioritised youth entry, assuming minimal need for adult retraining.

- Qualifications were often employer-led, emphasising practical mastery over theoretical breadth.

- Completion rates were tied to long-term commitments, reducing dropout but limiting adaptability.

- Funding models supported extended programmes, with less emphasis on modular learning.

Example (electrical trade)

Apprentices learned wiring under a master electrician, expecting to remain in the field without further formal training.

Between 2010 and 2026, UK vocational careers shifted from linear progression to non-linear models due to technological disruption, economic instability, and demographic changes. Automation and AI reduced demand for routine skills, while gig economy growth encouraged portfolio careers, with 78% of employers noting the end of traditional ladders. Policy reforms, like the 2017 apprenticeship levy, aimed at flexibility but highlighted mismatches, with skills shortages persisting in sectors like engineering. Labour market data shows increased career changes, with approximately 1 in 10 workers switching occupations over a decade. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated remote work and reskilling needs, while ageing workforces necessitated adult re-entry. Evidence from reports indicates this non-linear model better suits dynamic economies, though it increases individual responsibility for continuous learning.

What this means in practice

- Workers frequently re-enter training mid-career to adapt to new roles.

- Qualifications became modular, allowing stackable credentials over time.

- Employer demands focused on transferable skills rather than trade-specific loyalty.

- Funding shifted towards short courses, reducing barriers to re-entry.

- Career advice emphasised lifelong learning, with less reliance on single-occupation paths.

Example (electrical trade)

Electricians retrained for EV charging amid green tech shifts, moving beyond initial qualifications.

Adult participation in UK apprenticeships and vocational routes has risen sharply since 2010, with over-25s accounting for approximately 40% of starts by 2026, driven by skills shortages, job market volatility, and policy expansions removing age limits. Economic factors like automation displaced workers, prompting reskilling, while the apprenticeship levy encouraged employer uptake for existing staff. Data shows starts for this group grew amid post-recession recovery and pandemic shifts, with participation reaching 761,500 in 2024/25. This necessitates training design focused on flexibility, recognising prior experience to shorten durations, and modular delivery to fit work-life balances. Evidence highlights the need for blended learning, reducing off-the-job requirements, to improve completion rates and address underskilling projections for 20% of the workforce by 2030.

What this means in practice

- Programmes incorporate recognition of prior learning to accelerate completion.

- Delivery uses part-time, online formats to accommodate employment.

- Funding prioritises high-demand sectors, enhancing employer involvement.

- Assessment focuses on competence, reducing theoretical barriers.

- Support includes career guidance for mid-life transitions.

In UK electrical work, continuous iterative training is mandatory due to evolving regulations like BS 7671 updates, requiring compliance for legal safety standards under the Electricity at Work Regulations 1989 and Part P of Building Regulations. Amendments, such as A4:2026, introduce new requirements for installations, inspection, and testing, mandating skilled persons to maintain competence. Failure to update risks non-compliance, invalidating certifications and exposing workers to liability. Evidence from industry guidance shows training ensures adherence to national standards, with competent person schemes demanding periodic refreshers. This creates a cycle of requalification, as outdated knowledge can lead to unsafe practices, unlike optional CPD which lacks enforcement.

What this means in practice

- Electricians must complete 18th Edition courses for each amendment.

- Inspections require current knowledge, invalidating old certifications.

- Schemes like NICEIC enforce updates for membership.

- Training integrates practical assessments to verify ongoing competence.

- Non-compliance can halt work, affecting contracts.

Example (electrical trade)

BS 7671 A4:2026 demands updated surge protection knowledge, making retraining essential for safe installations.

Knowledge-based qualifications, like Level 2/3 diplomas, focus on theoretical understanding through exams and workshops, covering principles like circuit design and regulations. Competence-based validation, via NVQ portfolios and AM2 assessments, requires workplace evidence of practical application, proving real-world skills under observation. The gap arises as knowledge alone does not demonstrate job readiness, leading to bottlenecks in employment access without NVQ/AM2, which demand 12–24 months of on-site experience. Evidence shows this creates delays, with learners accumulating certificates but lacking portfolios, exacerbating skills mismatches in trades. Systems require both for full qualification, but limited workplace opportunities hinder progression.

What this means in practice

- Knowledge qualifications enable entry-level roles but not independent work.

- Competence validation demands employer supervision, limiting self-study.

- Bottlenecks occur in portfolio building without jobs.

- Assessment capacity strains, delaying AM2 slots.

- Gaps reduce completion rates, perpetuating shortages.

Example (electrical trade)

Theory covers BS 7671, but NVQ/AM2 requires on-site installation evidence.

UK skills shortages persist despite rising participation due to high dropout rates (approximately 40% in apprenticeships), mismatches between training and employer needs, and insufficient job-readiness focus. Leaks include poor completion from inadequate support, with only one-third finishing programmes; skills gaps in essential employability areas like digital literacy; and regional disparities limiting access. Evidence shows 80% of employers face shortages, projected to affect 20% of workers by 2030. Economic factors like low wages deter retention, while fragmented systems fail to align qualifications with vacancies, creating underskilling in key sectors.

What this means in practice

- Enrolment surges but completions lag due to financial barriers.

- Training lacks practical elements, reducing job-readiness.

- Mismatches arise from outdated curricula.

- Leaks worsen in underserved regions.

- Employer disengagement limits placements.

- Underskilling persists without ongoing support.

Example (electrical trade)

High enrolment in diplomas, but leaks in NVQ completion delay qualified electricians.

Self-employment and subcontracting in UK trades have transferred training burdens to individuals, as contractors avoid costs for non-employees, with 37% of construction workers self-employed. This shifts expenses for qualifications, tools, and updates to workers, increasing financial strain without employer support. Time for training competes with income generation, reducing uptake. Responsibility falls on individuals for compliance, like tax and insurance, with evidence showing lower investment in subcontracted labour. Policy gaps exacerbate this, as levies favour larger firms, leaving self-employed to self-fund amid skills demands.

What this means in practice

- Individuals bear course fees without reimbursement.

- Time off for training means lost earnings.

- Re-qualification updates are self-managed.

- Limited access to group schemes increases costs.

- Responsibility for competence proof falls personally.

Example (electrical trade)

Self-employed electricians fund 18th Edition updates independently.

Regulations like BS 7671 updates and Part P create a qualification treadmill by mandating periodic compliance, requiring electricians to retrain for amendments (e.g., A4:2026) to maintain certifications. Inspection and testing standards enforce ongoing verification, with non-compliance risking legal penalties under Building Regulations. This cycle demands continuous learning, as evidence shows updates every few years align with safety advancements. Deadlines for implementation force timely requalification, shifting systems from one-time to iterative models, though it ensures safety amid technological changes.

What this means in practice

- Updates trigger mandatory courses every 3–5 years.

- Part P requires scheme registration with refreshers.

- Inspections demand current documentation.

- Deadlines enforce retraining timelines.

- Treadmill increases costs but enhances safety.

Example (electrical trade)

BS 7671 amendments require repeated 18th Edition qualifications.

Skills Bootcamps are not a replacement for traditional apprenticeships; they address short-term upskilling for adults, lasting up to 16 weeks with job interview guarantees, focusing on rapid employability in high-demand areas. Apprenticeships provide in-depth, long-term training (12+ months) with extensive on-the-job experience. Bootcamps solve immediate skills gaps but fall short in technical trades by lacking depth, leading to lower completion in complex fields and insufficient practical mastery. Evidence shows 59% dropout in construction, highlighting limitations for roles needing prolonged competence building.

What this means in practice

- Bootcamps suit quick reskilling, not foundational training.

- Apprenticeships build occupational standards over time.

- Shortfalls include limited assessment rigour.

- Employer involvement is interview-based, not embedded.

- Funding is targeted, restricting scale.

Example (electrical trade)

Bootcamps cover basics but lack AM2-level competence for full installations.

A genuinely adult-friendly UK vocational pathway would feature flexible funding via the Adult Skills Fund, covering modular courses with subsidies for low-skilled adults. Flexibility includes part-time, online delivery to fit work schedules. Recognition of prior learning (RPL) reduces durations by validating experience, with fixed minimum hours. Assessment builds capacity through blended methods, ensuring scalability. Employer involvement integrates via levy reforms for uniform subsidies, encouraging placements. Evidence supports this for reskilling, addressing 20% underskilling projections by 2030.

References

- Office for National Statistics – Employment and Labour Market Statistics – https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket

- Department for Education – Apprenticeship Funding Rules 2025-2026 – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/apprenticeship-funding-rules-2025-to-2026

- Department for Education – Adult Skills Fund Funding Rules – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/adult-skills-fund-funding-rules

- GOV.UK – Skills Bootcamps Information – https://find-employer-schemes.education.gov.uk/schemes/skills-bootcamps

- Skills England – Occupational Pathways and Standards – https://skillsengland.education.gov.uk/

- Education Hub – Free Courses for Adults – https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2024/01/free-courses-and-qualification-for-adults-to-boost-their-skills

- Resolution Foundation – Mountain Climbing Report (Labour Market Transitions) – https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2026/01/Mountain-climbing.pdf

- Resolution Foundation – Ready for Change (Skills and Technology) – https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Ready-for-change-report.pdf

- OECD – Apprenticeship in England, United Kingdom – https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2018/04/apprenticeship-in-england-united-kingdom_g1g8cb6e/9789264298507-en.pdf

- OECD – Promoting Better Career Mobility for Longer Working Lives in the United Kingdom – https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/promoting-better-career-mobility-for-longer-working-lives-in-the-united-kingdom_2b41ab8e-en.html

- Institute for Fiscal Studies – Labour Market Transitions Research – https://ifs.org.uk/publications/labour-market-transitions

- Construction Industry Training Board – Skills and Training Report 2021 – https://www.citb.co.uk/media/wnpb2l0k/citb-skills-and-training-report-2021.pdf

- Engineering Construction Industry Training Board – Skills Transferability Report – https://www.ecitb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Skills-Transferability-Report-FA.pdf

- House of Commons Library – Further Education Funding Research Briefing – https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-10365/CBP-10365.pdf

- Edge Foundation – Skills Shortages Bulletin – https://www.edge.co.uk/documents/546/DD1660_-_Skills_shortages_bulletin_summary_2025_FINAL.pdf

- CIPD – Lifelong Learning in the Reskilling Era – https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/2025-pdfs/8930-lifelong-learning-in-the-reskilling-era-report-web.pdf

- CEDEFOP – Changing Nature of VET in England Case Study – https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/england_cedefop_changing_nature_of_vet_-_case_study.pdf

- UK Parliament – Education Select Committee Skills Report – https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5901/cmselect/cmeduc/666/report.html

- Institution of Engineering and Technology – Engineering Skills Statistics 2025 – https://www.theiet.org/media/press-releases/

- National Audit Office – Department for Education Overview 2024-25 – https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Department-for-Education-Overview-2024-25.pdf

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 17 February 2026. This article examines structural evolution of UK vocational education systems using electrical trades as case study. Statistical data from ONS, DfE, Resolution Foundation, OECD, and sector bodies (CITB, ECITB) reflects 2018-2025 period with projections to 2026 where noted. Apprenticeship demographic data shows approximate 40% adult participation in 2025 starts based on DfE reporting. Skills shortage figures from industry reports and employer surveys. Qualification stacking patterns based on regulatory requirement analysis and sector body guidance. Adult Skills Fund and Skills Bootcamp details reflect 2025-26 funding rules. System limitations and assessment capacity constraints based on practitioner reports and sector analysis. This article provides systemic analysis of vocational education trends, not individual career advice. Consult training providers for specific programme details and career guidance professionals for personal planning. Information current as of February 2026 but subject to policy updates, funding changes, and regulatory evolution. Next review scheduled following significant changes to Skills England structure, apprenticeship funding, or vocational qualification frameworks.