Common NVQ Portfolio Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Added comprehensive guide on common NVQ portfolio mistakes including evidence quality errors, coverage gaps, documentation failures, assessment process mistakes, VARCS compliance requirements, evidence mapping strategies, contemporaneous recording importance, employer cooperation factors, cost implications of delays, and preventative strategies ensuring first-time acceptance

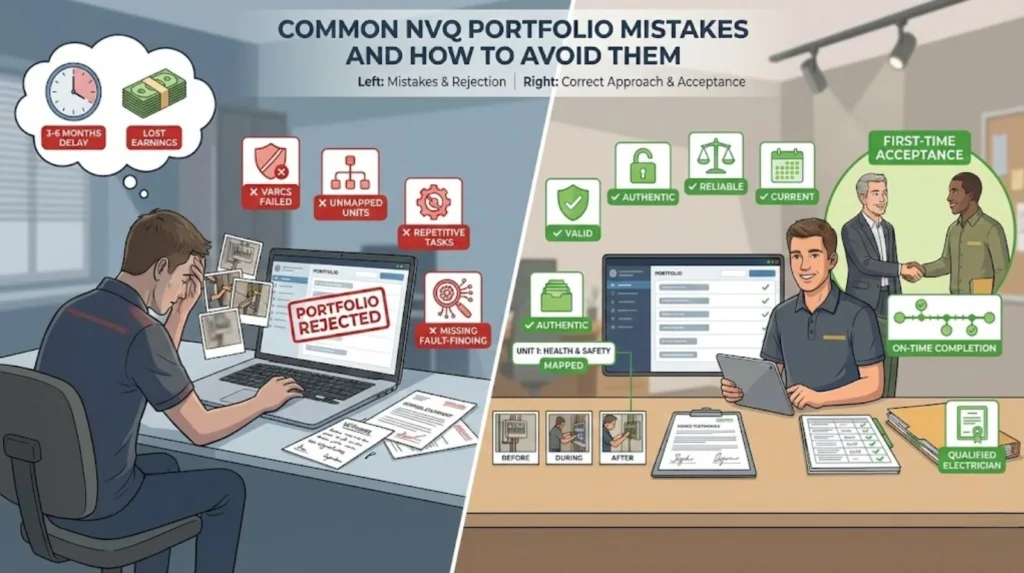

You’ve worked 15 months on electrical sites documenting installations across domestic rewires, commercial fit-outs, and industrial maintenance. Your portfolio contains 150 photos showing consumer unit installations, containment work, testing procedures, and circuit commissioning. Witness statements from qualified supervisors confirm you completed documented work. Testing certificates prove installations met BS 7671 requirements. Then your assessor reviews the portfolio and sends everything back requesting major corrections. What went wrong? The brutal reality is that volume doesn’t equal quality in NVQ portfolios. Having 150 photos means nothing if they don’t prove your personal competence through clear attribution, proper context, and systematic mapping to unit performance criteria.

The most common portfolio mistake isn’t technical incompetence. It’s evidence presentation failing to demonstrate competence assessors can verify against City & Guilds standards. Vague photos showing finished installations without documenting your involvement during critical stages. Generic narratives copying template descriptions rather than explaining specific decisions you made on particular jobs. Evidence uploaded to random folders without mapping to exact unit criteria assessors must verify. Witness testimonies lacking detail about what you actually did versus what the team accomplished collectively. The competence exists, but the evidence fails proving it according to awarding body requirements.

Internal Quality Assurers (IQAs) reject approximately 30% to 40% of first-submission portfolios requiring corrections before proceeding to AM2 gateway. The rejection reasons repeat predictably across thousands of learner experiences. Missing start-to-finish job narratives explaining progression from planning through commissioning. Evidence not clearly attributable to you personally versus supervisor or team contributions. Repetitive task documentation (50 socket installations) without varied examples proving competence breadth. Insufficient fault-finding or testing context leaving diagnostic skills unverified. Incomplete witness testimonies missing signatures, dates, or specific task descriptions. The corrections aren’t minor adjustments. They’re systematic evidence rebuilding adding 3 to 6 months to completion timelines whilst you gather replacement documentation from jobs finished months earlier.

The cost implications extend beyond frustration. Every month delayed at improver wages (£24,000 to £28,000 annually) versus qualified wages (£35,000 to £45,000) costs £900 to £1,400 in lost earnings. A six-month delay from evidence quality problems costs £5,400 to £8,400 in delayed qualified status. Extended training provider enrolment beyond standard 18 to 24 month timelines often triggers £500 to £1,000 additional fees. Multiple assessor visits correcting evidence problems cost £200 to £400 per visit. The financial pressure makes evidence quality discipline worth daily effort preventing expensive mistakes that compound over months.

Portfolio mistakes fall into predictable categories: evidence quality errors (vague photos, missing narratives, unclear attribution), coverage gaps (repetitive tasks, missing fault-finding, insufficient work variety), documentation failures (unsigned testimonies, generic RAMS, inconsistent dates), assessment process mistakes (delayed assessor contact, unmapped evidence uploads, misunderstanding direct observation requirements), and behavioural planning errors (retrospective evidence gathering, assuming experience suffices, poor contemporaneous recording). Each category creates specific problems assessors identify during reviews, resulting in targeted correction requests that consume weeks or months depending on severity.

Understanding these common mistakes and implementing preventative strategies from day one transforms portfolio building from frustrating trial-and-error into systematic competence documentation. The patterns are so consistent that training providers can predict portfolio problems from employment type, evidence collection habits, and assessor engagement frequency. Learners starting with employers offering work diversity, maintaining daily evidence logging discipline, and engaging assessors at 20% to 30% completion for early feedback complete portfolios 40% to 50% faster than those discovering problems at final submission. The difference isn’t luck or natural ability. It’s systematic application of evidence quality principles preventing predictable mistakes before they become expensive corrections. For complete details on NVQ Level 3 portfolio evidence requirements breakdown including VARCS compliance standards and assessor expectations, see our comprehensive NVQ evidence guide.

Evidence Quality Errors (The Most Common Rejections)

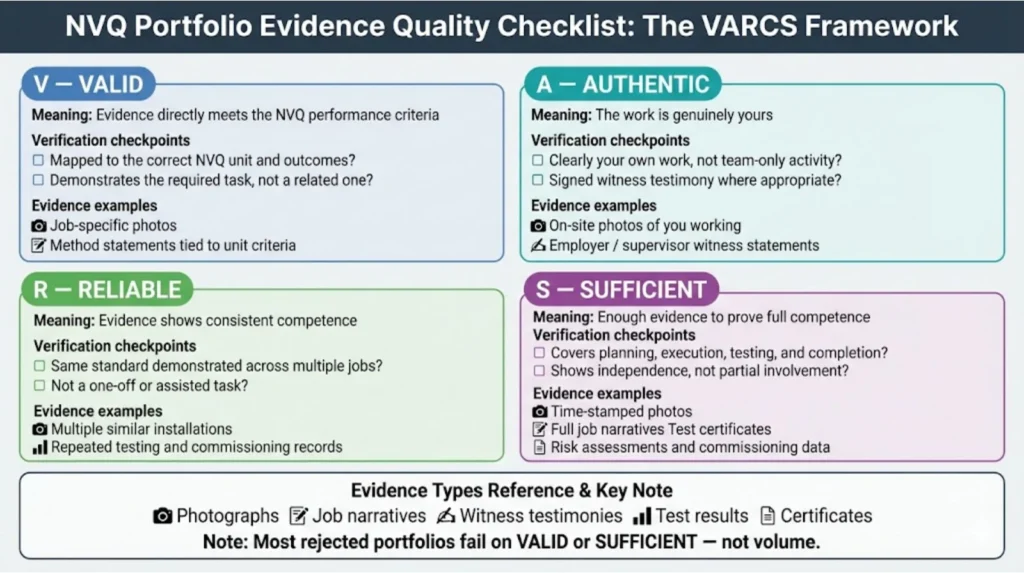

Evidence quality problems cause more portfolio rejections than any other category because they undermine fundamental verification assessors must complete. The problems aren’t obvious to learners uploading evidence but become immediately apparent when assessors apply VARCS criteria (Valid, Authentic, Reliable, Current, Sufficient) required by City & Guilds standards.

Vague photos without context represent the single most common quality error. A photo showing finished consumer unit installation tells assessors nothing about your involvement in the work. Did you install the unit personally, terminating all circuits and conducting verification testing? Did you assist a supervisor who completed critical terminations whilst you dressed cables? Did you simply photograph your supervisor’s completed work claiming it as evidence? Without contextual information explaining your specific role, cable routing decisions you made, termination sequence you followed, and testing verification you conducted, the photo proves nothing about personal competence.

The correction strategy requires photo sets showing installation progression. Before photos documenting initial conditions and planning considerations. During photos showing you personally conducting critical tasks (terminating circuits, installing containment, conducting tests). After photos showing finished compliant installations with your face visible confirming personal involvement. The three-photo progression proves competence assessors can verify versus single finished-product photos raising attribution questions.

Missing start-to-finish job narratives compound photo quality problems by failing to explain installation context, decision-making processes, or problem-solving approaches. Assessors reviewing photos need accompanying narratives answering specific questions. What was the installation purpose and circuit requirements? Why did you select particular cable sizes, containment types, or protective devices? What challenges did you encounter and how did you resolve them? What testing sequences did you follow and what results confirmed compliance? What BS 7671 regulations governed installation choices?

Thomas Jevons, our Head of Training with 20 years experience, explains the testing documentation gap:

"Testing certificates alone don't prove competence. We need narratives explaining how you conducted safe isolation before testing, why you selected specific test sequences, what readings you expected versus obtained, and how results confirmed BS 7671 compliance. A schedule of test results without the methodology story leaves assessors unable to verify you actually conducted tests versus copying supervisor's results onto blank certificates."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

The narrative requirement isn’t creative writing assessment. It’s competence verification through explanation. Assessors judge whether narratives demonstrate understanding of electrical principles, regulation requirements, and professional decision-making versus mechanical task completion following supervisor instructions. The narrative depth separates qualified electricians capable of independent work from improvers still requiring close supervision.

Evidence not clearly attributable to you personally creates immediate rejection because awarding bodies require proof of individual competence, not team performance. Photos showing multiple electricians working on installations without identifying your specific contributions fail attribution requirements. Witness testimonies stating “the team installed the distribution board” without clarifying you personally terminated circuits versus assisted with cable pulling fail attribution standards. Job completion certificates crediting company work without employee-specific details fail attribution verification.

The attribution solution requires first-person documentation. Narratives written using “I” statements explaining “I selected 2.5mm² cable based on circuit load calculations”, “I conducted insulation resistance testing following prove-test-prove sequence”, “I verified Zs values met BS 7671 requirements for protective device operation”. Photos showing you personally conducting tasks with your face visible confirming involvement. Witness testimonies specifying “the candidate personally terminated all final circuits whilst I observed, demonstrating proper stripping lengths and torque application”.

Blurry photos or poor lighting conditions creating technically unusable evidence waste assessor time and trigger resubmissions. Assessors cannot verify termination quality, cable identification, or installation compliance from photos where critical details are invisible due to image quality problems. The standard requires sufficient clarity for IQAs reviewing assessor decisions to independently verify evidence quality without accessing original installations.

The quality threshold means close-up photos showing termination details clearly, well-lit images revealing cable colours and sizing, and multiple angles documenting installation methods assessors can verify against BS 7671 requirements. Smartphone cameras provide adequate quality if used properly (good lighting, steady hands, close proximity to work). The rejection isn’t camera equipment limitations. It’s poor photographic technique failing to capture verification details assessors require.

Coverage Gaps (The Timeline Killers)

Coverage gaps extend completion timelines more dramatically than quality errors because discovering missing task types 14 to 18 months into portfolio building often requires new employment finding work diversity unavailable at current roles. The gaps aren’t immediately obvious but emerge during systematic assessor reviews identifying unit criteria lacking sufficient evidence.

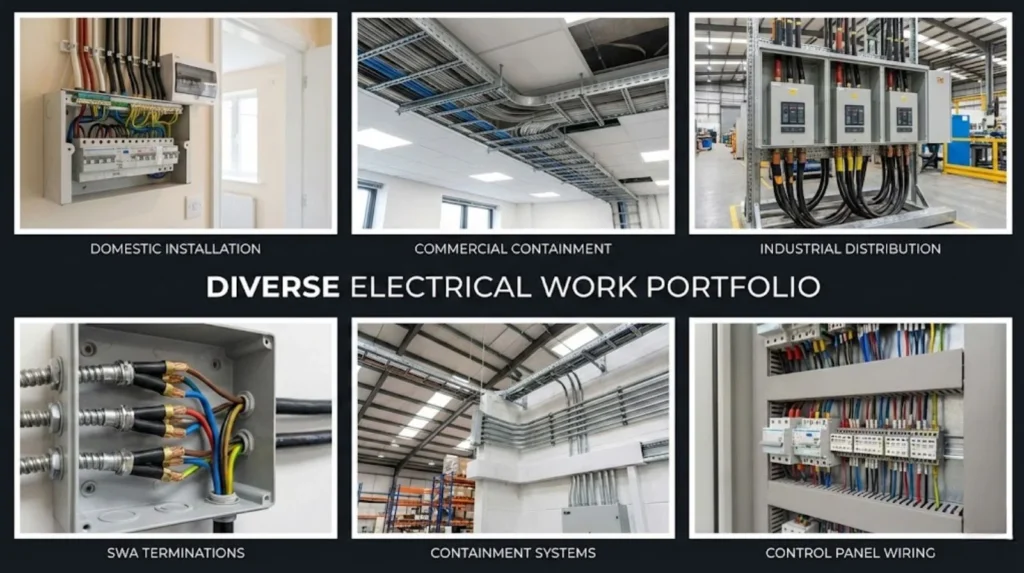

Repetitive task documentation across units creates coverage problems assessors identify through breadth analysis. Submitting 40 photos of plastic trunking installations proves you can install plastic trunking competently. It doesn’t prove competence installing cable tray with manual bends, steel conduit systems, or ladder rack in industrial environments. NVQ requirements demand evidence breadth demonstrating capability across varied containment types, cable categories, and environmental conditions. Repetition proves consistency in narrow task performance, not versatile competence across electrical installation range.

The containment example extends to cable types, circuit configurations, and environmental contexts. Evidence showing exclusively twin-and-earth domestic installations doesn’t prove SWA armoured cable termination competence required for outdoor circuits. Evidence from housing developments doesn’t prove three-phase distribution knowledge needed for commercial installations. Evidence from new-build projects doesn’t prove fault-finding and remedial work competence required for maintenance roles. Each gap discovered late in portfolio building extends timelines 2 to 6 months whilst learners seek employment providing missing evidence opportunities.

Lack of fault-finding or testing context represents the most problematic coverage gap because these tasks are often reserved for qualified electricians on sites, leaving improvers with limited diagnostic exposure. Unit 311 specifically requires fault diagnosis evidence proving you can identify circuit problems, conduct systematic testing isolating fault locations, and implement appropriate repairs or modifications. Many learners reach 80% to 90% portfolio completion before discovering this gap, then struggle manufacturing fault-finding opportunities from routine installation work.

The fault-finding solution requires proactive evidence gathering rather than waiting for natural fault occurrence. Arrange assessor visits where you demonstrate diagnostic procedures on test rigs or planned scenarios. Document any genuine faults encountered during commissioning (incorrect polarity, poor continuity, inadequate insulation resistance) explaining identification methods and correction approaches. Request involvement in remedial work or periodic inspection tasks providing fault diagnosis exposure. The proactive approach prevents coverage gaps discovered too late for natural correction.

Insufficient variation of work environments compounds coverage problems by limiting evidence to single sector demonstrations. Learners working exclusively domestic installations lack commercial and industrial experience proving competence in varied contexts. Those working only commercial fit-outs lack domestic consumer unit experience or industrial heavy machinery supply knowledge. The sector limitation becomes critical when assessors require evidence breadth across BS 7671 applications in different building types and usage categories.

Joshua Jarvis, our Placement Manager, explains the employment decision impact:

"Learners accepting any electrical job without considering evidence requirements often regret that decision 18 months later. Domestic-only employment creates commercial and industrial evidence gaps requiring job changes mid-portfolio. Starting with employers offering work diversity (housing developments including three-phase supplies, commercial fit-outs, small industrial maintenance) accelerates completion versus piecing together evidence from multiple employers sequentially. The employment decision affects portfolio timeline more than learner organisation."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

The work variety strategy requires employment selection prioritising evidence opportunities over immediate wage maximisation. A £2 per hour wage difference (£4,160 annually) becomes irrelevant when employment diversity enables 12 to 15 month completion versus 24+ months requiring job changes mid-portfolio. The long-term qualified wage access (£35,000 to £45,000) far exceeds short-term improver wage variations (£22,000 to £28,000). Strategic employment thinking prevents coverage gaps derailing completion timelines through inadequate work exposure.

Missing inspection and testing depth beyond basic commissioning verification creates another common gap. Portfolios demonstrate installation competence but lack periodic inspection evidence, EICR completion experience, or remedial work recommendations proving you understand verification processes beyond new installations. The inspection competence often determines AM2 readiness because practical assessments include existing installation evaluation alongside new circuit installation tasks.

Documentation Failures (The Administrative Killers)

Documentation problems create portfolio delays through administrative correction cycles rather than competence inadequacy. The failures prevent assessors verifying otherwise adequate evidence because supporting paperwork lacks essential elements validating authenticity and compliance.

Generic RAMS (Risk Assessments and Method Statements) attached without job-specific context fail documentation requirements. Uploading 50-page company safety manuals doesn’t prove you conducted risk assessment for specific installations being evidenced. Assessors need job-specific RAMS identifying hazards particular to documented work (working at height during tray installation, live cable proximity during additions to existing installations, confined space access for underground cable work) and explaining control measures you implemented (scaffold use, isolation procedures, ventilation requirements, permit systems).

The RAMS requirement isn’t bureaucratic box-ticking. It’s verification that you considered safety before starting work rather than installing first and considering hazards retrospectively after incidents occur. Job-specific RAMS demonstrate professional approach to installation planning including hazard identification, risk evaluation, and control measure selection proving competence beyond mechanical task performance.

Incomplete job sheets lacking essential verification details undermine evidence authenticity. Job sheets missing client addresses, installation dates, circuit descriptions, or certification references create authentication concerns assessors cannot resolve without additional verification. The incomplete documentation raises questions about whether work actually occurred as described or evidence was fabricated from generic descriptions.

The job sheet completeness standard requires dates matching witness testimony and photo metadata timelines, specific location information assessors can verify through employer confirmation, detailed circuit descriptions identifying installation scope (6-way consumer unit serving lighting and socket circuits, new 32A radial supply for workshop equipment, three-phase distribution board modification), and certification references linking installation evidence to test results and commissioning documentation.

Unsigned or poorly written witness testimonies represent the most common documentation failure causing immediate rejection. Witness testimonies lacking supervisor signatures, printed names, contact details, or qualification credentials fail authentication requirements. Generic testimonies stating “the candidate is competent” without specific task descriptions fail verification standards. Testimonies contradicting photo evidence or containing dates inconsistent with employment history fail reliability checks.

The witness testimony quality threshold requires signatures from qualified electricians with JIB Gold Cards or equivalent credentials, specific task descriptions explaining “the candidate personally terminated all circuits in the four-bedroom property consumer unit installation on 15 March 2025 whilst I observed”, dates matching job completion timelines and photo metadata, and supervisor contact details assessors can verify if authentication questions arise. The detail level proves testimonies document genuine observation rather than completing templates as administrative favours.

Inconsistent dates across evidence components create authentication red flags triggering detailed IQA investigation. Job sheets dated 2024 but witness testimonies dated 2025 for identical work suggest retrospective fabrication. Photo metadata showing images captured months before or after job completion dates indicate borrowed evidence or timeline manipulation. Testing certificates dated weeks after installation completion without explanation suggest delayed verification or copied results from unrelated work.

The date consistency requirement means contemporaneous evidence gathering during job completion, photo timestamps matching job dates within reasonable margins (day-of or day-after completion), witness testimonies written promptly whilst supervisors remember specific work rather than months later from vague recollection, and testing certification completed during commissioning rather than retrospective documentation. The timeline alignment proves evidence authenticity assessors can verify through metadata cross-referencing.

Missing calibration certificates for testing equipment invalidate all test result evidence regardless of readings obtained. Assessors cannot verify test accuracy when multifunction testers lack current calibration proving measurement reliability. The calibration requirement typically means annual certification from manufacturers or approved laboratories confirming test instrument accuracy within acceptable tolerances. Learners arriving for assessment visits without calibration certificates face immediate evidence rejection requiring complete testing resubmission once calibration is verified.

Assessment Process Mistakes (The System Failures)

Assessment process mistakes stem from misunderstanding NVQ procedures rather than evidence inadequacy, creating delays through systematic errors requiring educational correction before progress continues. Learners unfamiliar with assessor expectations often benefit from following a structured framework such as the complete NVQ 2357 portfolio building roadmap, which clarifies evidence sequencing, observation timing, and assessor engagement before issues compound.

Misunderstanding direct observation requirements causes learners relying excessively on witness testimonies and photographic evidence whilst avoiding mandatory assessor observations. NVQ standards require assessors directly observing you performing critical tasks verifying competence through real-time evaluation. Witness testimonies and photos support direct observations but cannot completely replace them across all units. Learners submitting portfolios without scheduling assessor site visits discover this requirement at final review, then face 6 to 12 week delays coordinating observations with employers and assessors.

The direct observation necessity means minimum 2 to 4 scheduled assessor visits throughout portfolio building (depending on route and provider), observations covering critical tasks assessors must verify personally (safe isolation, testing procedures, complex terminations, fault diagnosis), and planning observations strategically when suitable work is scheduled rather than waiting until portfolio completion. The proactive observation scheduling prevents discovery at final review that primary evidence requirements remain unsatisfied.

Delaying assessor contact until late portfolio stages costs months in corrections addressing systematic evidence problems developing unchecked. The delay pattern repeats constantly across learners. Twelve months evidence gathering without assessor feedback, then discovery that 40% doesn’t meet standards because it wasn’t mapped properly, lacks sufficient attribution, or covers insufficient task variety. Early engagement (first assessor contact at 20% to 30% completion) catches errors when corrections are minor adjustments, not wholesale evidence replacement.

The assessor engagement strategy means initial portfolio review within 2 to 3 months of evidence gathering commencement, monthly or bi-monthly progress reviews identifying emerging problems before they compound, and open communication asking clarification questions rather than making assumptions about requirements. The regular contact transforms assessors from judges into guides preventing expensive mistakes through early intervention.

Uploading evidence without mapping to specific unit criteria creates organisation chaos forcing assessors spending hours searching random folders trying to match evidence against performance requirements. Unmapped evidence wastes assessor time and triggers portfolio returns requesting systematic reorganisation before assessment can proceed. The mapping requirement means each evidence item (photo, narrative, witness testimony, certification) explicitly tagged with unit numbers and performance criteria it satisfies (Unit 304, PC 1.1 and 1.2 for example), logical folder structures organising evidence by units making verification straightforward, and indexing systems allowing assessors quickly locating evidence proving specific criteria.

The mapping discipline prevents common scenarios where assessors identify evidence satisfying requirements but buried in wrong folders or unlabelled preventing verification. Time spent mapping evidence during upload is time saved preventing assessor frustration and portfolio returns requesting reorganisation consuming weeks of administrative corrections.

Assuming simulation or college workshop evidence satisfies competence requirements creates fundamental misunderstandings about NVQ assessment. Competence units require real workplace evidence demonstrating capability under normal site conditions including time pressures, client expectations, and coordination with other trades. College workshops provide controlled environments lacking workplace variables proving professional competence. Simulation is extremely limited in NVQ assessment (maximum 10% of evidence in specific circumstances) and cannot form portfolio foundations.

The workplace evidence requirement means all significant competence demonstrations occurring on actual construction sites, maintenance environments, or installation projects serving real clients, evidence gathered under normal working conditions rather than contrived setups optimised for perfect documentation, and understanding that theory learned in classrooms requires separate workplace demonstration proving practical application capability. Learners relying on college-based evidence discover this limitation at assessment requiring complete competence resubmission from workplace contexts.

Behavioural and Planning Errors (The Self-Inflicted Delays)

Behavioural mistakes create portfolio problems through poor planning, inadequate discipline, or misunderstanding competence verification requirements. These errors are entirely preventable through systematic approaches but remain surprisingly common.

Leaving evidence collection too late in employment period forces retrospective documentation when job details fade from memory. Learners working six months then deciding to pursue NVQ discover they cannot accurately reconstruct specific installations, circuit details, problem-solving approaches, or testing results from completed projects. The retrospective evidence becomes generic template filling lacking specific authenticity assessors verify through detailed questioning.

The contemporaneous recording requirement means starting evidence collection from day one of employment (or day one of NVQ registration if already employed), daily or weekly job logging capturing circuit types, cable sizes, installation methods, testing results, and any problems encountered whilst details remain fresh, and immediate photo documentation during installations rather than weeks later when sites are inaccessible. The real-time discipline prevents vague evidence assessors reject for insufficient specificity.

Assuming experience speaks for itself without documented proof misunderstands fundamental NVQ principles distinguishing experience from competence. Experience means time spent working in field without necessarily demonstrating skill levels. Competence means proven ability carrying out tasks safely, consistently, and to industry standards verified through documented evidence. Ten years experience means nothing for NVQ purposes without contemporary evidence proving you currently perform work meeting BS 7671:2018+A2:2022 requirements.

The documentation necessity means treating NVQ as fresh competence verification regardless of experience duration, providing same evidence detail for basic tasks (socket installation) as complex tasks (three-phase distribution modification) because assessors verify everything against current standards, and understanding that historical experience claims require contemporary demonstration proving capability hasn’t degraded or regulation knowledge hasn’t become outdated.

Not keeping contemporaneous records creates reliability questions assessors cannot resolve without substantial additional evidence. Notes written months after job completion lack specific details (actual circuit numbers, precise cable routing decisions, specific testing sequences followed) making verification problematic. Contemporaneous records written during or immediately after work contain authentic detail assessors recognise versus retrospective reconstruction missing specificity.

The contemporaneous standard means using smartphone note applications recording job details daily whilst on site, photographing during installations rather than weeks later when access is impossible, and writing installation narratives within days of completion whilst problem-solving approaches and regulation considerations remain clear. The timeline discipline creates evidence quality assessors can verify through detail richness impossible to fabricate retrospectively.

Over-reliance on volume without quality focus creates portfolios containing 200+ photos telling assessors nothing versus focused portfolios with 40 to 60 well-documented jobs proving comprehensive competence. The volume trap stems from misunderstanding that quantity impresses assessors when actually evidence relevance, attribution clarity, and context completeness determine acceptance. Ten annotated photos showing start-middle-end progression with detailed narratives outweigh 100 unlabelled finished-product images providing no verification value.

The quality focus means ruthless evidence curation uploading only photos clearly showing your involvement and proving specific criteria, comprehensive narratives for fewer jobs rather than brief descriptions for many, and systematic mapping ensuring every evidence item serves verification purpose. The targeted approach prevents assessor frustration sorting through irrelevant documentation searching for proof buried amongst clutter.

Ignoring employer cooperation requirements until problems emerge wastes months discovering employers won’t support evidence needs. Employers denying assessor site access, restricting photography due to confidentiality, limiting work diversity to single task types, or refusing witness testimony provision create insurmountable evidence barriers discovered too late for employment changes preventing delays. The cooperation verification means discussing NVQ requirements during employment interviews confirming employer understanding of assessor visit needs, establishing early communication with supervisors willing to provide detailed witness testimonies, and identifying work variety limitations requiring supplementary employment or placement arrangements. The proactive approach prevents discovering cooperation problems 12 months into portfolio building when changing employment means starting evidence collection afresh.

Failing to plan unit coverage systematically creates random evidence accumulation missing critical criteria. Learners upload evidence as jobs complete without verifying which units and performance criteria each piece satisfies. Twelve months later they discover Units 311, 314, and 317 remain substantially incomplete requiring targeted job hunting for specific task types. The systematic planning prevents coverage gaps through strategic evidence gathering ensuring all units progress proportionally.

The planning discipline means creating unit checklists at portfolio commencement identifying all performance criteria requiring evidence, weekly or monthly reviews verifying coverage progress across all units not just favoured areas, and proactive job selection prioritising work filling gaps rather than repeating documented competence. The oversight prevents discovering at final review that 30% of criteria lack any supporting evidence requiring months of additional gathering.

How to Avoid These Mistakes (Systematic Prevention Strategies)

Portfolio success depends less on natural ability than systematic application of evidence quality principles preventing predictable mistakes before they require expensive corrections. The strategies aren’t complicated but demand consistent discipline throughout portfolio building.

Develop evidence planning approach from day one by creating comprehensive unit checklists identifying all performance criteria requiring verification, establishing weekly evidence review routines verifying coverage progress and quality standards, and maintaining job logs tracking which tasks provide evidence for specific units preventing coverage gaps through random accumulation. The planning discipline transforms evidence gathering from reactive documentation to strategic competence demonstration.

The planning tools include printed unit handbooks marked with highlighter as criteria are satisfied, digital spreadsheets tracking evidence items against performance requirements, and regular assessor consultations verifying coverage interpretation matches assessment expectations. The systematic tracking prevents discovering criteria gaps at final review requiring retrospective evidence hunting.

Adopt basic record-keeping habits ensuring evidence quality meets VARCS standards including timestamped photo documentation with descriptions explaining your involvement, actions taken, tools used, and outcomes achieved, daily or weekly job notes capturing specific details (circuit numbers, cable sizes, testing results, problems encountered, regulation considerations) whilst fresh in memory, and first-person narratives written using “I” statements proving personal attribution rather than team performance descriptions.

The record-keeping discipline means treating smartphones as evidence documentation tools not just communication devices, establishing evening or weekend routines transferring daily notes into formal narratives before details fade, and building photo-taking into installation workflow (before-during-after progression) rather than sporadic remembering. The habitual approach prevents evidence quality problems stemming from delayed documentation when specifics blur into generic recollection.

Brief supervisors properly for witness statement completion by providing templates including specific detail requirements (observed tasks, standards met, dates, supervisor credentials), explaining NVQ criteria so testimonies address performance requirements rather than generic competence claims, and requesting timely completion whilst job details remain fresh rather than months later from vague memory. The supervisor education transforms witness testimonies from administrative burdens into valuable supporting evidence assessors can verify.

The briefing approach means discussing witness testimony needs during job planning so supervisors understand observation expectations, providing printed criteria checklists supervisors reference when writing statements ensuring relevance, and offering to draft testimonies for supervisor review and signature (with their approval) ensuring detail quality whilst respecting their time constraints. The proactive support generates high-quality testimonies avoiding common rejection causes (vagueness, missing signatures, irrelevant content).

Prepare for assessor visits strategically by scheduling early and regularly (first visit at 20% to 30% completion, subsequent visits every 3 to 4 months) preventing systematic error accumulation, confirming suitable work is scheduled allowing competence demonstration across required criteria rather than simple maintenance not proving installation breadth, and conducting pre-visit evidence reviews with assessors identifying gaps requiring attention before formal assessment. The strategic preparation maximises assessment value whilst minimising correction cycles consuming months.

The visit preparation means treating assessors as guides not judges through open communication requesting clarification rather than making assumptions, coordinating with employers weeks in advance ensuring cooperation with site access and time allocation, and arriving with all required documentation (RAMS, calibration certificates, testing equipment) preventing administrative delays. The professional approach builds assessor confidence in your readiness accelerating verification decisions.

Implement continuous quality checking throughout portfolio building by reviewing uploaded evidence against VARCS criteria before assessor contact ensuring validity, authenticity, reliability, currency, and sufficiency, conducting monthly self-assessments identifying coverage gaps, quality problems, or documentation deficiencies whilst corrections are straightforward, and requesting peer reviews from qualified electricians or fellow learners providing external perspective on evidence clarity. The quality vigilance prevents problems accumulating unnoticed until final submission.

The checking discipline means allocating weekly time for portfolio review not just evidence upload, maintaining quality standards checklists verifying each item meets requirements before final submission, and treating evidence gathering as iterative refinement not one-time documentation. The continuous improvement approach ensures portfolio quality increases throughout building rather than requiring wholesale corrections at completion.

Understanding VARCS Compliance (The Quality Framework)

VARCS represents the quality framework City & Guilds uses evaluating portfolio evidence ensuring submissions meet national standards for competence verification. Understanding each criterion prevents common rejection causes whilst building evidence meeting assessment expectations from initial upload.

Valid evidence proves specific performance criteria claimed rather than general electrical competence. Photos showing cable installation must map to exact unit criteria about cable selection, routing, support, and termination rather than generic “I can install cables” claims. The validity requirement means reviewing unit handbooks identifying precise performance statements evidence must prove, ensuring every evidence item addresses specific criteria not vague competence areas, and mapping documentation explicitly to unit numbers and performance criterion identifiers preventing assessor confusion about verification intent.

Invalid evidence examples include photos of finished installations without explaining which specific criteria they prove, generic narratives describing jobs without linking to performance requirements, or testing certificates submitted without clarifying which unit criteria they satisfy. The validation process means asking “which exact performance criterion does this evidence prove” before upload, rejecting items failing clear criterion attribution, and maintaining evidence indices mapping every item to specific requirements.

Authentic evidence proves you personally completed documented work rather than observing supervisors or documenting team performance claiming individual credit. The authenticity standard requires clear attribution through first-person narratives, photos showing you conducting tasks with face visible confirming involvement, and witness testimonies specifying your individual contributions versus team activities. Inauthentic evidence includes photos showing multiple workers without identifying your specific role, passive voice narratives (“the circuit was installed”) avoiding personal attribution, or borrowed documentation from colleagues claimed as your work.

The authentication strategy means writing all narratives in first person using “I” statements, ensuring photos document your personal involvement not just team presence, requesting witness testimonies specifying “the candidate personally completed” rather than “the team achieved”, and understanding that assessors verify authenticity through detailed questioning about specific jobs during professional discussions catching fabricated claims through inconsistent details.

Reliable evidence proves consistent competence across multiple examples rather than one-off successful task completion. Single photo showing excellent termination quality doesn’t prove reliable competence. Multiple examples across different jobs, cable types, and environmental conditions prove consistent professional standards. The reliability requirement means providing multiple evidence instances for each performance criterion from varied contexts, ensuring quality standards remain consistent across all submissions not just selected best examples, and understanding assessors judge whether competence shown is habitual versus fortunate occasional success.

Unreliable evidence patterns include varying quality across submissions suggesting some document your work whilst others show supervisor’s installations, inconsistent approaches to similar tasks indicating lack of systematic methodology, or exceptional results appearing anomalous compared to typical evidence suggesting coaching or fabrication. The reliability development means maintaining consistent documentation standards across all jobs, building systematic approaches to common tasks proving methodology understanding, and avoiding quality variations triggering assessor authenticity concerns.

Current evidence gathered during NVQ registration period proves contemporary competence meeting current standards rather than historical capability potentially outdated. Work completed before registration doesn’t satisfy currency requirements regardless of quality. The currency standard means all evidence dated during active registration period (typically 18 to 24 months from enrolment), photo metadata confirming images captured during registration timeframe, and understanding that retrospective evidence from previous employment fails currency verification even when demonstrating high competence.

The currency compliance means starting evidence collection immediately upon registration not relying on historical work, ensuring photo timestamps match registration period through metadata verification, requesting witness testimonies during registration period not retrospectively for older work, and understanding that competence must be demonstrated currently not historically proven. The contemporary focus ensures qualifications verify present capability not past achievements.

Sufficient evidence provides comprehensive proof removing reasonable doubt about competence. Insufficient evidence leaves assessors unable to verify claims requiring additional documentation. Sufficiency isn’t quantity dependent (100 photos don’t guarantee sufficiency whilst 20 might provide adequate proof). It’s comprehensiveness ensuring all performance criteria aspects are addressed through appropriate evidence depth.

Insufficient evidence examples include single photos attempting to prove multiple complex criteria, brief narratives lacking detail needed for verification, or testing certificates without methodology explanations proving you conducted tests personally. The sufficiency development means providing evidence depth matching criteria complexity (simple criteria need less documentation than complex installation demonstrations), ensuring all criterion aspects are addressed not just superficial coverage, and understanding assessor perspective verifying whether submitted evidence removes doubt about capability.

The Cost of Portfolio Mistakes (Financial Reality)

Portfolio mistakes aren’t just frustrating administrative delays. They’re expensive timeline extensions costing thousands in lost wages, additional fees, and opportunity costs delaying career progression.

Direct timeline costs from evidence corrections add 3 to 6 months average delay for major quality problems requiring systematic evidence rebuilding, 6 to 12 months for coverage gaps requiring new employment finding missing task types, and 2 to 4 weeks per correction cycle for minor documentation fixes (missing signatures, unclear mapping, insufficient narratives). The cumulative delays from multiple mistake categories compound creating 12 to 18 month total extensions transforming advertised 18 month completion into 30 to 36 month reality.

Lost earnings from delayed qualified status represent the largest financial impact. Every month stuck at improver wages (£24,000 to £28,000 annually) versus qualified wages (£35,000 to £45,000) costs £900 to £1,400 in wage differential. Six-month delay costs £5,400 to £8,400. Twelve-month delay costs £10,800 to £16,800. The earnings impact dwarfs training costs making evidence quality discipline financially rational even when requiring daily effort preventing mistakes.

Training provider extension fees add direct costs when completion exceeds standard enrolment periods. Most providers include 18 to 24 month access in registration fees (£1,800 to £2,500 typical ranges). Extensions beyond standard periods often trigger £500 to £1,000 additional fees for continued assessor access, portfolio platform use, and administrative support. Multiple extensions compound costs whilst delaying qualified status simultaneously reducing income and increasing expenses.

Additional assessor visit costs accumulate when evidence problems require repeated observations. Standard packages typically include 2 to 4 visits. Additional visits for corrections cost £200 to £400 each depending on provider and travel requirements. Learners requiring 6 to 8 total visits due to evidence problems pay £400 to £1,600 extra beyond initial fees. The visit costs are preventable through proper preparation and early assessor engagement catching problems before formal assessment attempts.

Opportunity costs from delayed progression affect career development beyond immediate wages. Qualified status enables self-employment opportunities, specialist role access (inspection and testing, design verification, supervision), and professional development pathways (HNC/HND, chartership routes) unavailable to improvers. Each month delayed represents lost networking opportunities, skill development limitations, and career progression obstacles affecting long-term earnings beyond immediate wage differentials.

The financial analysis makes prevention investment worthwhile. Daily 15 to 30 minutes maintaining evidence quality (proper photo documentation, contemporaneous note-taking, systematic mapping) prevents delays costing thousands through delayed qualified status and additional fees. The discipline return on investment exceeds 100:1 when comparing time invested preventing mistakes versus financial impact of corrections through extended timelines.

If you’re starting NVQ portfolio building or struggling with evidence quality problems preventing acceptance, here’s what successful completers recommend based on thousands of learner experiences and assessor feedback patterns.

Start with systematic planning before gathering first evidence by reviewing complete unit handbooks identifying all performance criteria requiring verification, creating tracking spreadsheets or checklists monitoring coverage progress across units, and establishing weekly evidence review routines ensuring quality standards and coverage balance rather than random accumulation. The planning foundation prevents coverage gaps and quality problems developing undetected until final submission.

Implement daily evidence discipline maintaining VARCS compliance through timestamped photo documentation during installations showing before-during-after progression with your involvement clearly visible, contemporaneous note-taking capturing specific details (circuit numbers, cable sizes, testing results, problems encountered, regulation considerations) whilst fresh in memory, and first-person narratives written within days of job completion explaining decision-making processes, problem-solving approaches, and BS 7671 compliance verification.

Engage assessors early at 20% to 30% completion requesting portfolio reviews identifying systematic errors whilst corrections are minor adjustments, scheduling regular progress meetings (monthly or bi-monthly) discussing coverage development and quality standards preventing assumption-based mistakes, and asking clarification questions about requirements rather than making guesses leading to months of misdirected effort. The early engagement transforms assessors from final judges into development guides preventing expensive mistakes through proactive intervention.

Select employment strategically prioritising evidence opportunities over immediate wage maximisation by seeking employers offering work diversity across domestic, commercial, and industrial sectors, verifying employer cooperation with NVQ requirements during interviews (assessor site access, photography permissions, witness statement support), and understanding that £2 to £3 hourly wage differences become irrelevant when employment quality affects 12 to 24 month completion timeline variations costing thousands in delayed qualified wages.

Build supervisor relationships supporting witness testimony quality by explaining NVQ criteria during job planning so supervisors understand observation expectations, providing templates including specific detail requirements (tasks observed, standards met, supervisor credentials, dates), and requesting timely testimony completion whilst job details remain fresh rather than months later from vague recollection. The proactive supervisor education generates high-quality supporting evidence avoiding common rejection causes.

Maintain continuous quality verification preventing mistake accumulation by conducting monthly self-reviews checking uploaded evidence against VARCS criteria (valid mapping, authentic attribution, reliable consistency, current timing, sufficient depth), requesting peer feedback from qualified electricians or fellow learners providing external perspective on evidence clarity, and treating portfolio building as iterative refinement continuously improving quality rather than one-time documentation requiring wholesale corrections at completion.

Our approach at Elec Training recognises portfolio mistakes cause more completion delays than technical incompetence, with 30% to 40% of first submissions requiring major corrections adding 3 to 6 months to timelines and costing £5,000 to £8,000 in delayed qualified wages. We provide comprehensive evidence quality support including detailed VARCS compliance checklists preventing common rejection causes, monthly portfolio reviews catching systematic errors early whilst corrections are minor adjustments, witness testimony templates ensuring supervisor statements meet detail requirements, assessor engagement coordination scheduling observations strategically when suitable work is available, and employment vetting confirming contractors offer work diversity and NVQ cooperation preventing mid-portfolio job changes disrupting evidence gathering.

Call us on 0330 822 5337 to discuss how our systematic evidence quality approach prevents common portfolio mistakes costing thousands through timeline extensions and additional fees. We’ll review your current evidence identifying quality gaps, coverage problems, or documentation deficiencies before assessor rejection. We’ll provide specific correction strategies addressing VARCS compliance requirements and unit mapping standards. We’ll coordinate with your employer ensuring cooperation with witness testimonies, assessor visits, and work variety access. We’ll establish regular review schedules catching problems early preventing expensive corrections discovered at final submission. For complete details on comprehensive NVQ Level 3 evidence quality standards guide including VARCS framework, mapping procedures, and acceptance criteria, see our detailed portfolio quality resource. Portfolio mistakes aren’t inevitable learning experiences requiring expensive corrections. They’re predictable patterns preventable through systematic evidence quality discipline applied from day one. The successful completers aren’t luckier or naturally better at documentation. They’re strategic about employment selection, disciplined about contemporaneous recording, proactive about assessor engagement, and systematic about quality verification preventing problems before they require months of corrections. Our evidence quality approach treats portfolio building as systematic competence demonstration following established standards rather than trial-and-error discovery learning from expensive mistakes discovered too late for efficient correction.

References

- City & Guilds – 2357 NVQ Diploma in Electrotechnical Technology Handbook – https://www.cityandguilds.com/

- EAL Awards – NVQ Level 3 Diploma in Installing Electrotechnical Systems and Equipment – https://www.eal.org.uk/

- NET (National Electrotechnical Training) – Candidate Guidance and Assessment Information – https://www.netservices.org.uk/

- Elec Training – How to Build Your NVQ Level 3 Electrical Portfolio – https://elec.training/news/how-to-build-your-nvq-level-3-electrical-portfolio/

- ElectriciansForums.net – Portfolio Questions and Assessor Advice – https://www.electriciansforums.net/

- Medium / Charanjit Mannu – How to Build Your NVQ Level 3 Electrical Portfolio Without Losing Your Mind – https://medium.com/@charanjit_55251/

- Electrical EWA – Experienced Worker Assessment FAQs and Requirements – https://www.electrical-ewa.org.uk/

- OneFile – Digital Portfolio Platform for NVQ Evidence Management – https://www.onefile.co.uk/

- Aptem – Work-Based Learning and NVQ Assessment Platform – https://www.aptem.co.uk/

- Smart Assessor – E-Portfolio System for NVQ Qualifications – https://www.smartassessor.com/

- JIB (Joint Industry Board) – ECS Cards and Qualification Requirements – https://www.jib.org.uk/

- IET (Institution of Engineering and Technology) – BS 7671 Wiring Regulations – https://www.theiet.org/

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 6 January 2026. This page is maintained; we correct errors and refresh sources as City & Guilds assessment standards, VARCS compliance requirements, and portfolio platform procedures evolve. Evidence quality standards reflect City & Guilds 2357 and EAL NVQ Level 3 requirements current as of November 2025. VARCS framework (Valid, Authentic, Reliable, Current, Sufficient) reflects awarding body guidelines published 2023 to 2025. Portfolio rejection statistics (30-40% first submission) reflect training provider reporting and assessor feedback patterns observed 2022 to 2025. Timeline and cost estimates reflect typical learner experiences with evidence quality corrections based on forum discussions, provider data, and employment market analysis. Digital platform capabilities (OneFile, Aptem, Smart Assessor) reflect functionality as of Q4 2025. Next review scheduled following significant City & Guilds updates to assessment procedures or TESP modifications to evidence standards (estimated Q2 2026).